Theater review: ‘Richard III’ deftly reimagines Shakespeare’s classic through standout acting

The ensemble of “Richard III” gathers in a circle and gazes up at an individual in a crown standing on a ladder. A Noise Within in Pasadena is presenting an adaptation of William Shakespeare’s play through March 8. (Courtesy of Craig Schwartz)

“Richard III ”

Feb. 8 to March 8

A Noise Within

By Reid Sperisen

Feb. 19, 2026 2:30 p.m.

Warning: Spoilers ahead.

With “Richard III,” a villainous rise to power feels prescient and profoundly entertaining.

A Noise Within in Pasadena is presenting an adaptation of William Shakespeare’s “Richard III” through March 8. This version of the story, directed by Guillermo Cienfuegos, remains faithful to the original source material while folding Shakespeare’s five-act play into a two-act production that chronicles Richard III’s ascension to the throne by ordering most of his relatives to death. The combination of a stellar lead performance, dynamic supporting cast and simplistic but effective production design make this 2.5-hour spectacle a gripping theatrical experience, even if the music and costuming could have been more immersive.

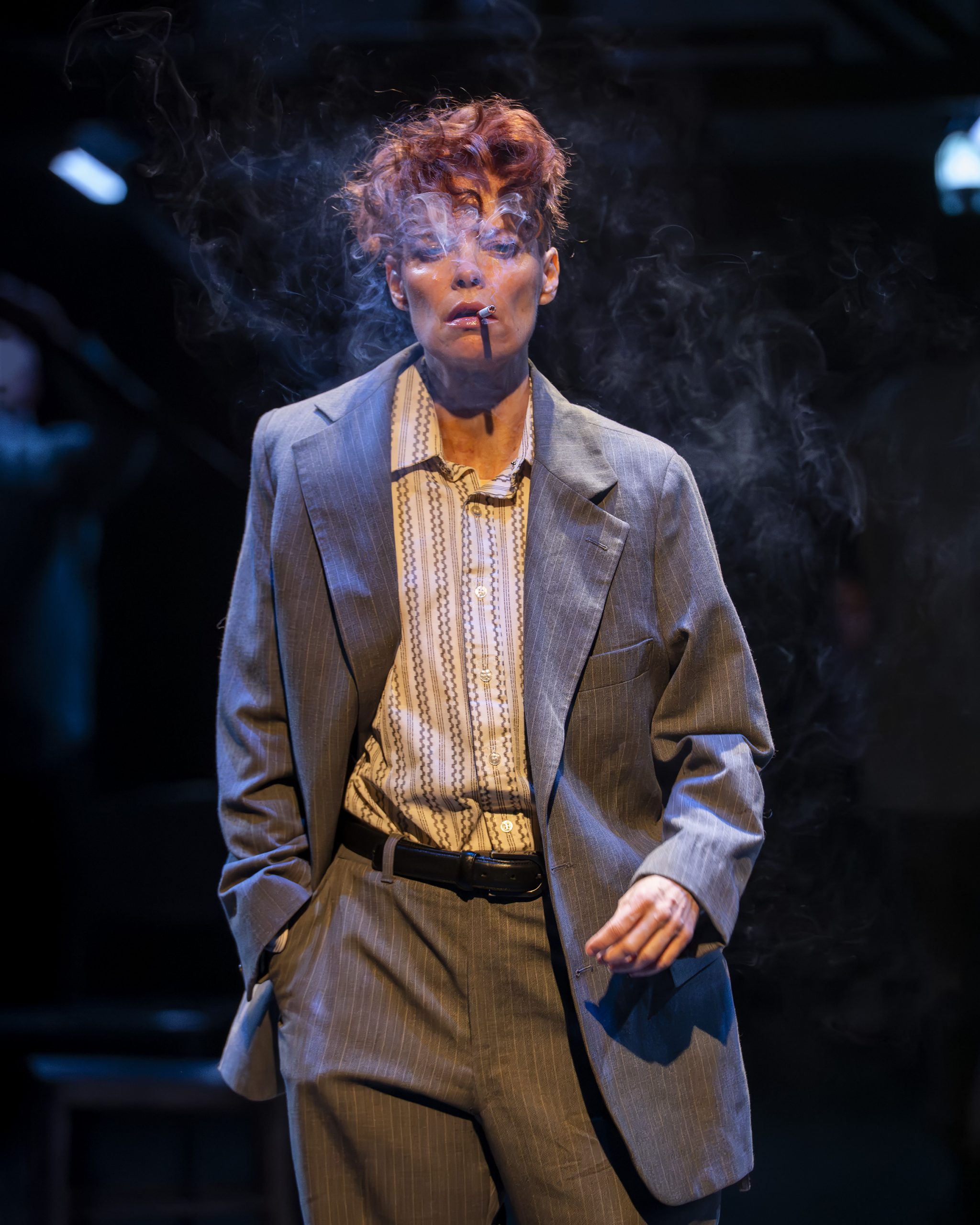

The production is anchored by actress Ann Noble’s layered performance in the titular role, with most of the dramatic tension hinging upon her delivery of several extensive soliloquies. Casting Noble in this role was a stroke of genius, as her confident charisma and seamless ability to glide between menacing adroitness and gleeful taunting keeps the audience on its toes. One of the strongest scenes in the entire show is Richard III’s first soliloquy, during which Noble appears alone and fills the stage with the smoke of her cigarette as she begins to clue the audience into her plans to take the throne from King Edward IV by means of murder and deceit.

Noble’s acting is not the only standout, as each of the supporting actresses find a different way to own the stage. Veralyn Jones is convincingly horrified by the bloodshed as Richard mother, the Duchess of York, and Richard’s sister-in-law Queen Elizabeth (Lesley Fera) is given several meaty scenes to process her grief in heated exchanges with Richard. The most moving performance comes from Trisha Miller as Queen Margaret, whose husband and son were killed prior to the play’s start and arrives to deliver a warning to Edward. Even though her stage time is limited, Margaret’s prophecies of violence are seared into the viewer’s memory long after the final curtain, thanks to Miller’s chilling stage presence and guttural, melancholic cries.

[Related: Album review: Charli xcx’s ‘Wuthering Heights’ reaches peaks in production, falls in songwriting]

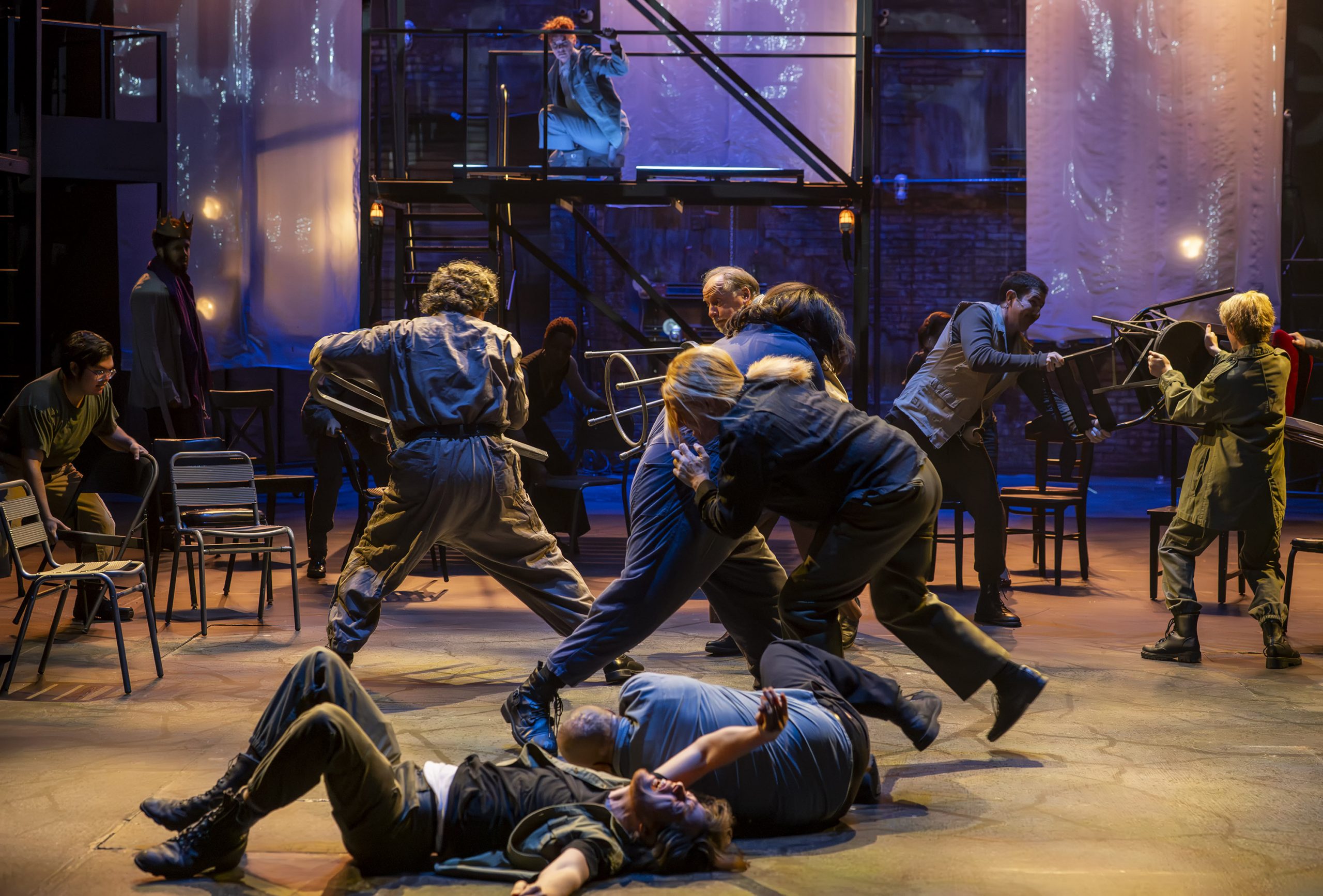

By comparison, the supporting male cast lacks the same dramatic flair and emotional catharsis. Some characters are rendered memorably enough, such as Richard’s brothers King Edward IV (Neill Fleming) and the Duke of Clarence (Randolph Thompson) in the scenes preceding their premature deaths. However, the Duke of Buckingham (Lynn Robert Berg) remains a flimsy caricature whose motives as Richard’s primary accomplice are never explored, even when he betrays Richard. Furthermore, the most underdeveloped character is Wes Guimarães as the Earl of Richmond, the rival who anticlimactically vanquishes Richard as sheets of white and red paper fall onto the battlefield of the stage below.

Despite the carnage as Richard’s male relatives fall one by one, there is a surprising jolt of humor throughout the show. This playfulness invigorates the play with tonal complexity and typically stems from Noble herself, such as in scenes where Richard attempts to woo the widowed Lady Anne (Erika Soto) or during interactions with his young nephews. A moment of morbid humor comes at the end of the first act when Richard reaches into a box containing the head of a murdered dissenter and struts around the stage admiring the blood pooling on his hand – a striking visual not easily forgotten.

In addition to the image of Richard’s bloody hand, one of the most spellbinding sequences comes toward the end of the second act, when Richard is haunted by nightmares of the characters he has ordered to be killed. On the eve of his final battle with Richmond, a tarplike curtain hangs across the stage as projections of his victims are cast upon it, wishing Richard will “despair and die.” Having the prerecorded video stare into the crowd forces the audience to feel the discomfort of Richard’s sins alongside him – a clever technique that makes the bloody consequences of Richard’s quest for power all the more devastating.

The dream sequence’s creative staging stands out compared to the production’s relative minimalism. Most scenes are framed with limited set pieces such as ladders and scaffolding that are meant to represent doorways or the interior of Richard’s castle, with the fanciest prop being Richard’s throne on wheels. For the sake of budgeting and ease, this approach makes sense and does not detract from the audience’s ability to imagine Richard’s changing locations.

The production is not without mishaps, particularly with the generic costumes that fail to transport the audience. The program declares the production is set in 1970s Britain, but more effort could have been undertaken to mark the aesthetics of this period rather than dressing every character in monotonous shades of gray. An exception is the costume for Margaret, which features red shoes and gloves that visually pop when Margaret lurks in the shadows of the stage.

[Related: Film review: ‘The Strangers: Chapter 3’ sabotages suspense with excessive exposition]

In addition to the underwhelming costumes, the play could have benefited from more frequent use of music, especially to add to the desired 1970s feeling. While some percussion and guitars could be heard during brief transitions, these moments were fleeting and impeded the music from creating a decisive mood. It would have been more appropriate for such instrumentation to punctuate Richard’s soliloquies, since the drama and tension of the play could have been intensified with a more elaborate sonic experience.

Overall, “Richard III” is not dramatically reimagining the Shakespeare material but still feels relevant to the contemporary theater ecosystem for its fresh take on Richard’s insatiable hunger for power. Political in its themes and provocative in its acting, this is a play with something to offer to longtime Shakespeare fans and casual theatergoers alike.

It might be a trek for Westwood readers to catch this play in Pasadena, but the journey is worthwhile for the storytelling value of “Richard III.”