Second Take: Historical dramas prefer to preserve neo-aristocracy, romanticize ruling class

(Ingrid Leng/Daily Bruin)

By Dylan Winward

Jan. 13, 2024 7:51 p.m.

This post was updated Jan. 15 at 7:48 p.m.

For a Hollywood bathed in privilege, it’s far too easy to romanticize the glamour of history.

Recent years have brought about a wave of historical dramas depicting clashes between aristocratic convention and revolutionary upheaval, with Sir Ridley Scott’s 2023 biopic “Napoleon” and Netflix’s Emmy-nominated historical series “The Crown” serving as just two recent examples. However, rather than looking back at history with an informed tone and a foundation of recent scholarship, Hollywood instead chooses to embrace the ruling class, even at the expense of the truth. By misleading audiences about the nature of the past, Hollywood exposes its preference for preserving a neo-aristocratic status quo.

If one were to sum up the plot of “Napoleon,” one could say it presents a vulgar Corsican upstart getting shown his place by a British aristocrat. In doing so, Scott’s depiction parrots outdated English narratives that are not only untrue but also dangerous.

Scott’s depictions of class narratives in “Napoleon” start at the very beginning of the film, with Napoleon curiously present at the execution of Marie Antoinette. In doing so, Scott at least implicitly positions class upheaval as the primary motivation for Napoleon’s rise to power. So far, so good.

However, it is after this that we begin to see Scott’s illusions fall apart. In the film, Napoleon seems to rise to power almost entirely by chance, discrediting his political knowhow. Despite the real-life Napoleon being described as intellectual and mathematically gifted, the film entirely skips any social, judicial or economic reforms, including the abolition of feudalism that significantly contributed to modern French life.

Napoleon is also depicted in the film as lacking artistic appreciation, presumably because of his relatively working-class background. While the real-life Napoleon contributed to collections at the Louvre Museum and the finding of the Rosetta Stone, Joaquin Phoenix’s character is seen needlessly firing a cannon at the pyramids of Egypt, seemingly for entertainment. This perpetuates the notion that people who are not born into wealth or expensive education are unable to appreciate the arts, gatekeeping culture as exclusively for the monied classes. Scott, whose brother told the Hollywood Reporter that they “never wanted for anything” as children, is consequently locking working class people out of the arts.

Scott also emphasizes all the wrong aspects of Napoleon’s relationship with his first wife, Josephine. In the film, she is shown flashing Napoleon and demonstrating bizarre sexual kinks, none of which derive from real life. Meanwhile, her royal-born replacement seems well-mannered and normal by comparison. The stark contrast between the two seems to suggest that the manor-born are more worthy to rule – a notion already outdated in 1950, never mind today.

Scott’s clear class biases are perhaps even more evident when it comes to his choice of which characters to spotlight in the plot. None of Napoleon’s marshals, who benefited from Napoleon’s meritocracy, had significant speaking roles in the film. It is almost as if Scott is writing Michel Ney, Louis-Nicolas Davout and Joachim Murat – the third of whom did not even have an on-screen counterpart – out of history to avoid confronting the reality of Napoleon as a promoter of social mobility and meritocracy.

Scott also depicts his film’s noble-born characters, like the Duke of Wellington and Charles-Maurice de Talleyrand-Périgord, as soft-spoken with some of the script’s most intelligent dialogue. Napoleon is portrayed as crass, petulant and immature, ranting at a British ambassador about boats. It suggests that only those who fit in with historical stereotypes about what leaders should look like are fit to make political decisions, a narrative which has nefariously excluded working-class candidates from political office for a generation.

Even Napoleon’s defeat at Waterloo is frustratingly portrayed as Wellington teaching Napoleon a lesson about manners, with the men meeting on a ship so Wellington can lecture Napoleon about his future. In addition to being historically inaccurate, this reduces a conflict between one of the world’s first modern republics and a traditional monarchy to a personal lesson in etiquette.

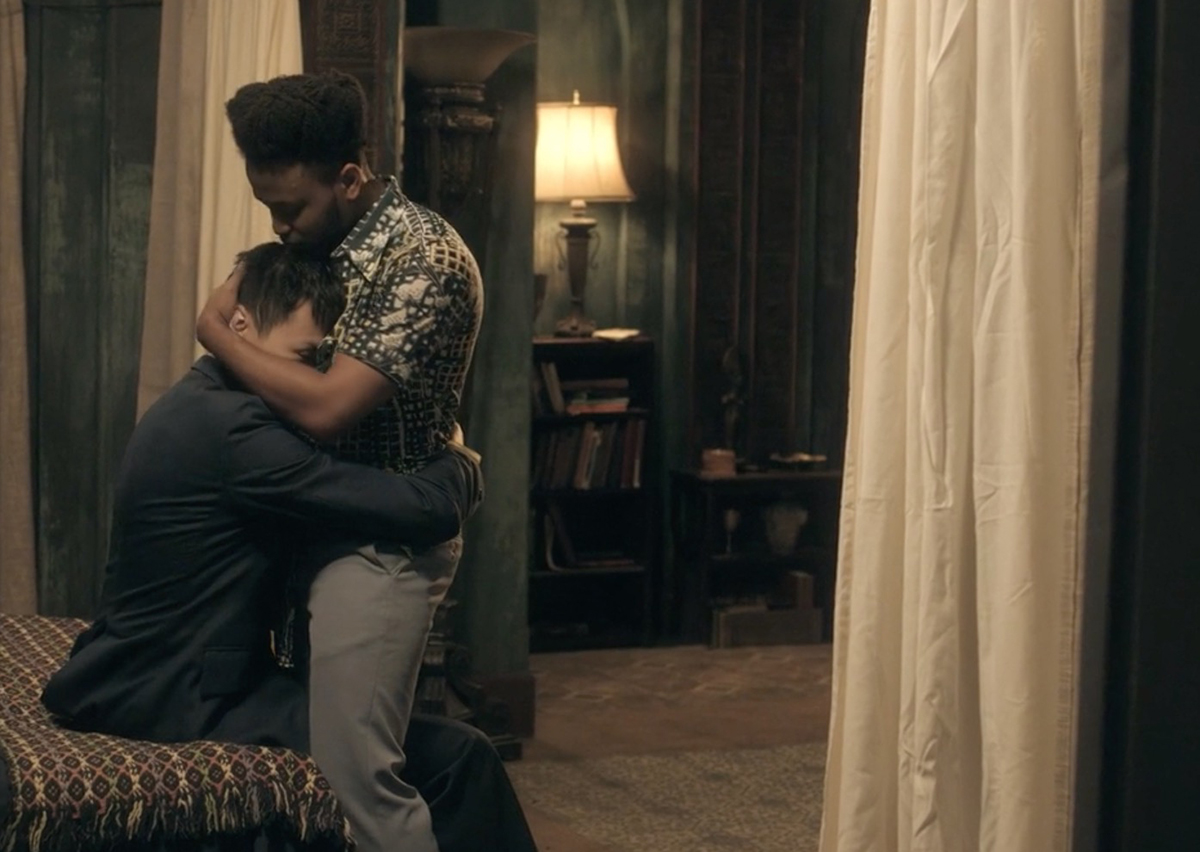

There are similar problems with Peter Morgan’s “The Crown,” a dramatized Netflix series about Queen Elizabeth II’s life. In the series, Morgan romanticizes the royal life by failing to focus on aristocratic missteps and instead lamenting the outsiders who criticize the queen.

In episode six of the sixth and final season, which seems to lack historical evidence, the queen of England is advised by her prime minister to slim down the size of the royal staff, many of whom hold hereditary roles. After an episode romanticizing their lives through entirely fictitious interviews, she concludes that doing so would destroy valuable traditions. Morgan’s message: Don’t mess with the luxuries of the upper class.

Similarly, the ostensible villain of the new season is Mohamed Al Fayed, a man depicted as being delusional and obsessed with conspiracy theories. In the series, he is shown as the biggest threat to the image of the monarchy. Meanwhile, Morgan choses to entirely ignore the real-life allegations of pedophilia against Prince Andrew, a known associate of Jeffrey Epstein. In doing so, Morgan is saying the problem is the delusional foreigner who rose from obscurity through hard work, not the philandering prince. Morgan, like Scott, depicts the upper class as people who can do no wrong and portrays social mobility as the enemy of happy endings.

Despite the aforementioned issues with historical fiction, many argue that the genre draws attention to issues people wouldn’t otherwise consider. After all, most British people would not even know about the Warden of the Swans or the Queen’s Guide to the Sands if they had not watched “The Crown.” Similarly, while Napoleon’s descendant Joachim Murat disparages the inaccuracies of the film, he still recommends people watch it to get them thinking about the former French emperor. Nonetheless, it seems more viewers will focus on the queen dining at the Ritz than think critically about the class implications of her privilege.

When it comes to historical films, it is easy to romanticize the ruling class. As the historical fiction Netflix romance “Bridgerton” has shown viewers, the music of the upper class is prettier, the costumes are more vibrant and the dialogue is more delicious. Even more bluntly, Matthew Vaughn’s 2014 spy movie “Kingsman: The Secret Service” suggests that it is manners rather than morality that “maketh man.”

But when you stop to think about all the Victorian-chic, who does it really serve?