Second Take: Uncovering the washed-out, white-centered world of BookTok

By Alston Kao/Daily Bruin

By Talia Sajor

Feb. 22, 2023 8:41 p.m.

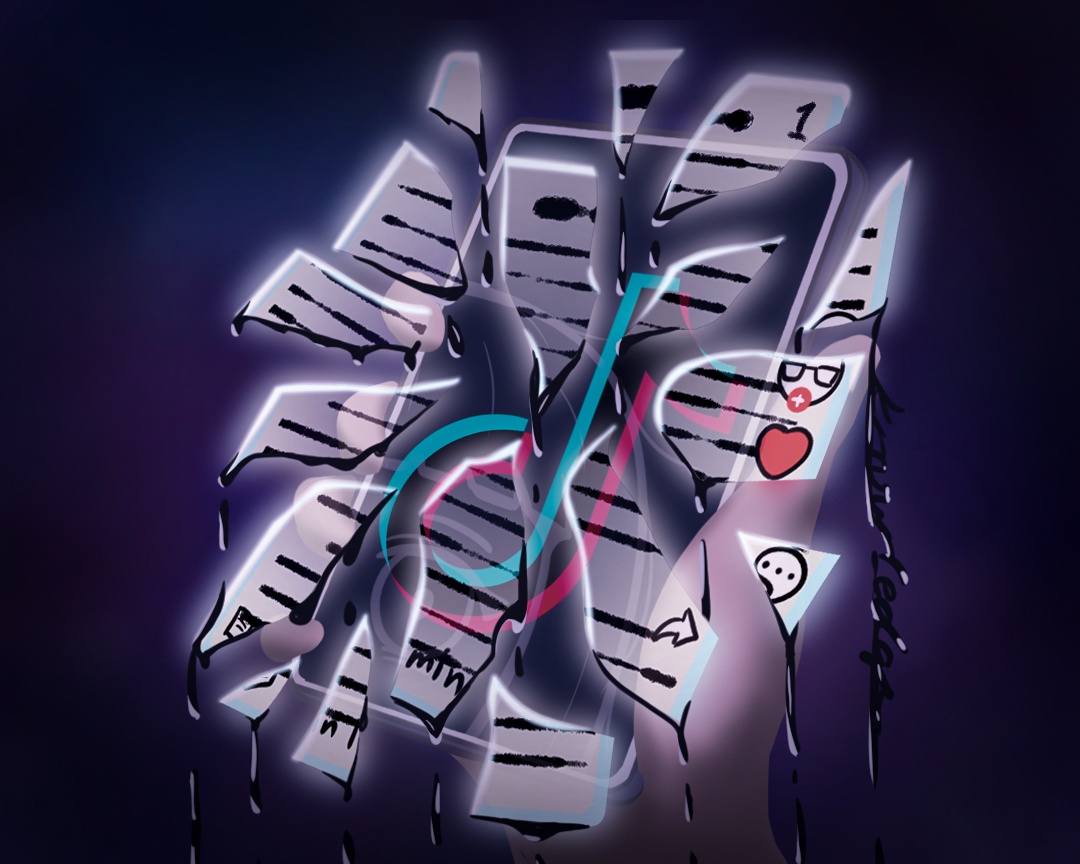

Literature has found a new, controversial home in the white-painted walls of TikTok.

As months stuck indoors during the COVID-19 pandemic helped propel the popularity of TikTok, a more niche community also emerged on the social media platform: BookTok. The app’s subculture features creators dedicated to promoting, reviewing and sharing a variety of books. While the literary side of TikTok may seem to fuel the reading revolution among members of Generation Z, BookTok’s content promotes the same palatable characters and experiences meant for a specifically targeted white audience, disregarding both readers and authors of color.

For example, among the popular titles are the respective works of Colleen Hoover, Taylor Jenkins Reid and Sally Rooney, including “It Ends With Us,” “Daisy Jones & The Six” and “Normal People,” all novels focusing on white characters written by white authors. As all of these books have received the treatment of a film or TV show adaptation, the transition from BookTok fame to the screen continuously perpetuates the oversaturation of white experiences.

Unfortunately, the pipeline of viral novels written about cisgender, heteronormative white stories is not a new phenomenon. Popular sites such as Wattpad and Archive of Our Own are similarly infamous for overproducing the same stories with dull, repetitive tropes. These works have also been produced for the screen, such as Anna Todd’s “After” series, based on her Wattpad-published Harry Styles fanfiction, and Netflix’s “The Kissing Booth” trilogy, written by Beth Reekles.

[Related: Second Take: Grammys continue to demonstrate lack of respect for the talent of Black artists]

In addition to the white leads, these stories also use the same stale and stereotypical plotlines. One of the most popular genres in the literary community is romance. Besides the illustrated carbon copy of the same bright-colored covers, the similarities also reside in the over used tropes used in these books. From best-friends-to-lovers to fake dating, a book’s ability to reach TikTok stardom demands more than just its stereotypical trope.

For instance, in “Get A Life, Chloe Brown,” author Talia Hibbert blends the “boy next door” and “opposites attract” cliches to tell the budding romance between the emotionally closed off, motorcycle-riding Redford “Red” Morgan and the methodical computer nerd, Chloe Brown. Even though Hibbert concocted the perfect recipe for BookTok to devour, the titular character goes against the typical rom-com protagonist – she is a plus-sized Black woman with a chronic illness. The novel never quite reached the same popularity on TikTok as other books, and that can only be attributed to the community’s refusal to go outside of their narrow-minded, white comfort zone seen in the works of Hoover, Rooney and Jenkins Reid.

The hyperexposure of these monotonous stories reveals a deeper issue in social media’s recent obsession with creating mass aesthetics and many younger teenagers feeling the need to categorize themselves as such. Characterized by Lana Del Rey’s discography and “heroin chic” persona, the newfound “sad girl” aesthetic also includes a reading list featuring Sylvia Plath’s “The Bell Jar” and Ottessa Moshfegh’s “My Year of Rest and Relaxation.” Besides the obvious white characters and microaggressions sprinkled within these novels, the target demographic of these books and aesthetic is young, white women who further promote the damaging romanticization of mental illnesses.

[Related: UCLA alumnus reflects on nonverbal expressions of love in ‘Baby Bao at Dim Sum’]

Another harmful theme among the novels promoted on BookTok is found in “Spicy BookTok.” Categorized by heavy and overly explicit smut, this genre toes a murky line between sexual degradation and romanticizing abuse and misogyny. In Hoover’s “November 9,” Ben, the supposed lover of protagonist Fallon, admits he “never wanted to use physical force on a girl before, but (he wanted) to push her to the ground and hold her there until the cab drives away” as she attempts to leave him. While Hoover could have made a point to her audience regarding the painfully disgusting toxic and possessive behavior demonstrated throughout the book, she and the rest of BookTok instead market the piece as an erotic, heartbreaking romance.

As society has advocated for accurate portrayals of diversity and human experiences within the entertainment industry, the same standard should be held in the publishing industry and reading community. Ultimately, uplifting the voices of people of color within literature needs to be just as prioritized as it is within other forms of media.

Until BookTok and the Internet as a whole begin to promote novels that go beyond the comfort of its bland white protagonists, not everyone should consider themselves well-read.