Life and Hip-Hop: Examining the complex relationship between music and politics

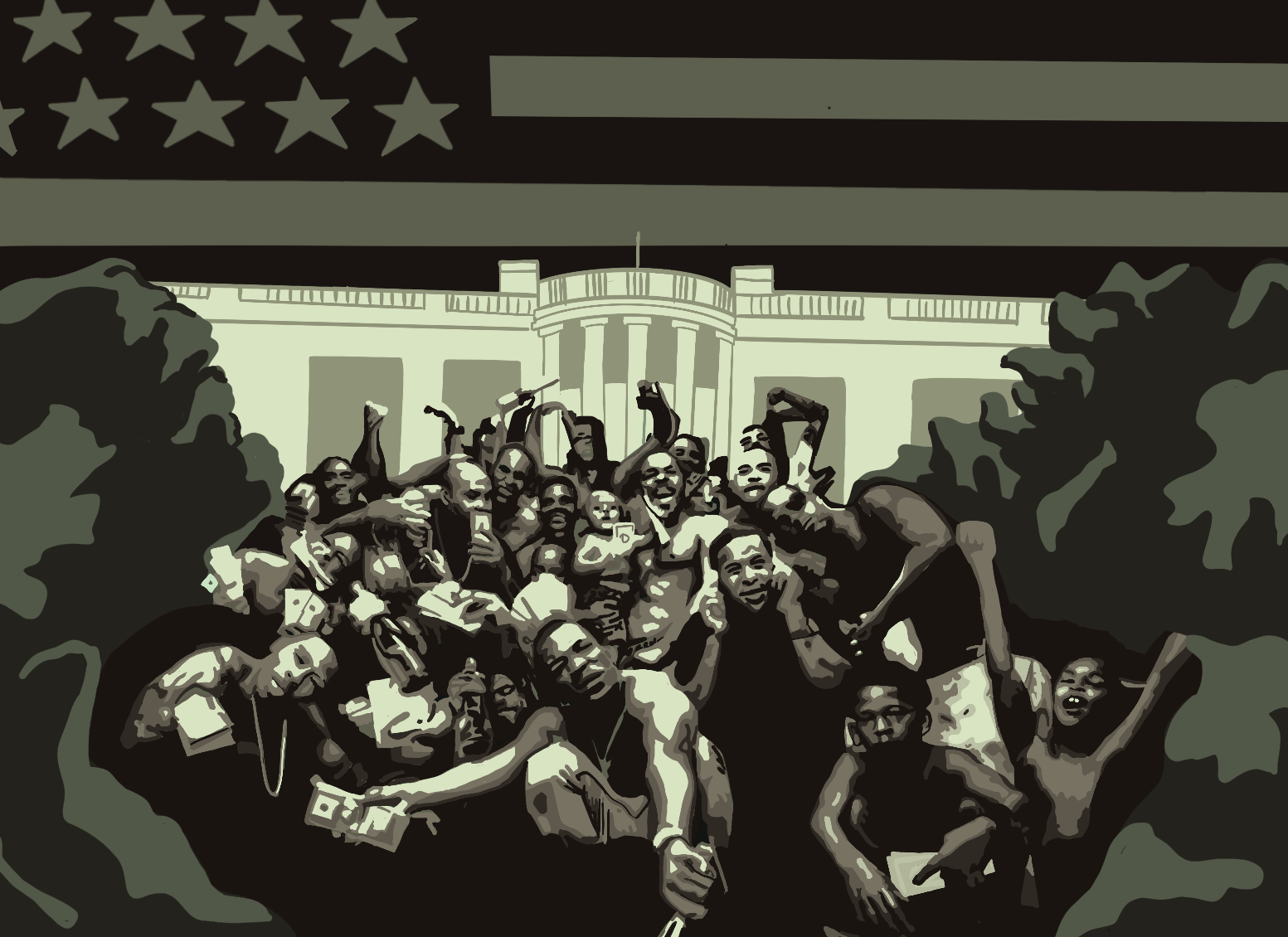

(Emily Dembinski/Illustrations director)

By EJ Panaligan

Nov. 5, 2020 12:19 a.m.

The impact of music extends far beyond the play and pause buttons. Formed in the 1970s as an underground movement, hip-hop has expanded into various art forms and musical subgenres – with rap specifically being one of the most popular musical styles among today’s youth. In “Life and Hip-Hop,” columnists Natalie Brown and EJ Panaligan explore and analyze how hip-hop intersects with and influences everyday aspects of life.

“I’m out for presidents to represent me/ I’m out for dead fuckin’ presidents to represent me.”

Queens, New York, rapper Nas initially presents a belief in the system of democracy in this line from the 1994 Q-Tip remix to his iconic song “The World Is Yours.” But the second half of the lyric reveals that he’s not at all interested in elected officials that represent his interests, but rather, the dead presidents’ faces on the dollar bills that signify his personal wealth.

It’s easy to see why Black hip-hop artists generally don’t have favorable outlooks on American politicians. The irreparable damage of slavery lingers today – even after decades of protests, movements and marches for the country to afford Black individuals basic civil and human rights. Those who are elected and sworn in to represent the citizens of the United States don’t always bear a great track record of having Black America’s best interests at heart.

And the reason why hip-hop’s relationship with politics has been largely contentious and pessimistic is because the genre has continuously reflected the Black experience in America. In political discourse and studies, politics are generally split into “big P” and “little P” – the public and the personal, both which played particularly prominent roles in hip-hop’s conception during the late 1970s in South Bronx, New York, said Shana Redmond, a professor in musicology and global jazz studies.

[Related: Life and Hip-Hop: Nipsey Hussle’s legacy of resisting gentrification in birthplaces of music]

The notion of personal politics contributes heavily into the idea of property, which she said goes all the way back to the days of slavery when Black bodies were under the ownership of American slaveowners. The emancipation of Black individuals meant they were able to steal themselves back and reclaim their ownership, which has influenced this through line of theft that is present in hip-hop’s conception, Redmond said.

“Hip-hop developed from this investment in seizing back resources that have been taken from (Black communities), so they’re stealing electricity for their turntables or borrowing breakbeats from existing music as a means of getting the party started,” Redmond said. “Hip-hop becomes a way out of no way and (Black artists are) able to actually make a world from from its barest kinds of resources and capacities.”

While these displays of personal politics in hip-hop are subtle at their core, examples of public politics are much more obvious. Redmond said hip-hop’s relationship to policing and imprisonment has been a very public one dating back to the late 1980s during the Reagan administration and the war on drugs, which criminalized drug addiction and targeted Black and brown communities. She cited examples of songs that directly spoke to Black issues of the time, such as N.W.A.’s 1988 song “Fuck Tha Police,” which outright declared the failure of policing as an institution in America.

[Related: Life and Hip-Hop: Exploring the origins of the association between drugs and music]

The concept of policing within hip-hop has also directly affected the music through the form of censorship, said Tabia Shawel, the assistant director of the Ralph J. Bunche Center for African American Studies. Committees like the Parents Music Resource Center, which was founded in 1984 and spearheaded by Tipper Gore, the wife of former Vice President Al Gore, sought to denounce hip-hop music for its lyrical themes and content by labeling albums with Parental Advisory labels, Shawel said.

“You’ve got politicians meddling into this process because they’re in agreement with the way in which hip-hop has been criminalized,” Shawel said. “They felt it glamorized deviant behavior, and therefore it needed to stop, (even though) we know that such lyrics can be found in a number of different genres.”

The PMRC proved this point with its “Filthy Fifteen” list, a compilation of popular songs in 1985 that exhibited themes of sex, drugs, violence and explicit language which they presented as examples at Senate hearings. Of all the songs on the list, none of them are hip-hop, suggesting the PMRC was just loosely grouping the genre in with examples of explicit popular rock and pop songs of the time.

Shawel said hip-hop has been able to transcend public and political scrutiny because of its radical nature, along with its ability to morph into different sounds and subgenres beyond its makeshift New York roots. Its impact as one of the most popular genres in the world has made it instrumental in expanding the global reach of ongoing racial injustice protests because of its insight into Black-specific issues, she said.

“(Hip-hop) breeds the prospect of unity among people who are often told that they should not like one another,” Shawel said. “But if we’re compassionate, and we all understand why it is that this system is continuously working to degrade or dehumanize a certain section of our society, then we have a better chance at becoming a united front and working toward dismantling that system.”

Nas was justified in “The World Is Yours” to hesitate in trusting the government or the systems that have failed Black Americans for decades now. But looking ahead, hip-hop has the unifying power to potentially amend a historically fractured relationship between Black communities and the leaders meant to serve them.