For UCLA community members, delay of student loan forgiveness poses challenges

(By Isabella Lee/Illustrations director)

When President Joe Biden announced a plan for student debt relief in August, Simona Grace said she finally felt like she had a chance to achieve her dream of attending graduate school.

Grace, a comparative literature alumnus, immigrated thousands of miles from Hungary. She overcame multiple financial and legal hurdles to transfer from community college to UCLA, her dream school. After Grace accumulated around $36,000 in debt, Biden’s announcement was the relief she needed to pursue a master’s degree, she said.

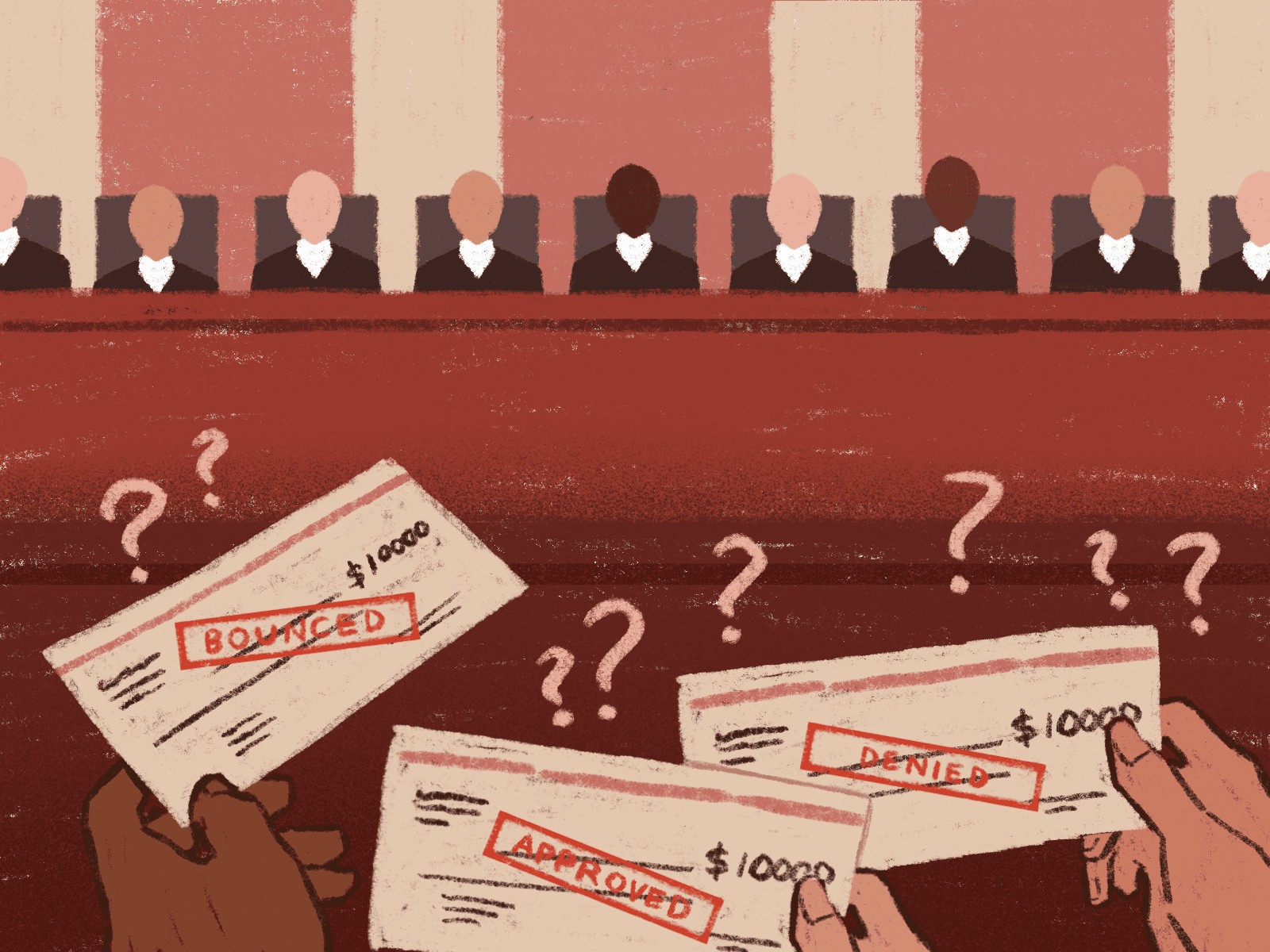

But that relief, which will forgive $10,000 for eligible borrowers with loans from the federal government, has been held up in court for months. The 8th United States Circuit Court of Appeals temporarily blocked the plan in November after several states, including Missouri and Arkansas, argued Biden’s decision would decrease state revenues. Though the Biden administration has appealed this decision to the Supreme Court with arguments set to begin Feb. 28, if the court fails to rule on the case before June 30, students’ payments will automatically resume 60 days later.

[Related: UCLA community members assert recent student loan forgiveness is positive start]

This holdup has been difficult, said Grace, who received a Pell Grant, a federal award given to undergraduate students with exceptional financial need. Under Biden’s decision, grant recipients such as Grace are eligible to have an additional $10,000 forgiven, totaling a potential $20,000. Around 30% of UCLA students were Pell Grant recipients in the 2019-20 academic year.

Both of the last two presidential administrations have used existing higher education laws to pause student loan payments in light of the COVID-19 pandemic. The Higher Education Relief Opportunities for Students Act of 2003 and Higher Education Act of 1965 give broad authority to the Secretary of Education to waive debt and modify payment collection, particularly in times of emergency, said law professor Joseph Fishkin.

While Fishkin said he believes federal law clearly allows the Biden administration and the Department of Education to forgive loans, the Supreme Court’s recent track record of decisions may indicate a stop to the forgiveness plan. The increasingly political and partisan discourse surrounding Biden’s action has also obscured the benefits it will provide to people, he added.

“The Supreme Court has a recent history of looking at actions that were kind of novel – new things, even if they seemed pretty clearly to fall within established authority, … and finding a way to, if not strike them down, at least take a pretty serious whack at them,” he said.

But, for some UCLA community members, the holdup impeding Biden’s decision means far more than just legal battles, as future aspirations depend on whether or not they can pay off their debts.

Keara Williams, an education doctoral student who applied for debt forgiveness, said any loan forgiveness will bring her a step closer to her dream of becoming the first in her family to own a home.

“Sometimes, I just have daydreams about the type of home that I want and how I want to decorate it and what location and how to build a family,” Williams said. “The idea of owning that – I think it’s exciting, it’s motivating, it’s hopeful, right? But when it’s blocked, all those feelings kind of just drop.”

Grace said that as a young mother, she was paying thousands of dollars for her son’s daycare just so she could go to work. With rising costs from her personal life and obligations, she said it was difficult to think about paying for her own education.

“The decisions that I had to make to earn a college degree is directly impacting my child’s ability to earn a college degree and pay for that degree,” Grace said. “It has become an issue of not just this generation, but now our children are affected by the debt that we have.”

Students of color, who are traditionally more likely to receive Pell Grants, are also disproportionately impacted by student loans, which the Biden administration noted in a press release. According to the press release, Black students are more likely to have to take out loans for school, and they are more likely to be Pell Grant recipients.

High costs have also reinforced barriers to higher education for Black students, Williams said. When they are able to pursue college or university, she said they are especially vulnerable to taking on student debt without the resources to support them. Though there are scholarships for students from a wide range of backgrounds at UCLA, resources aimed at supporting Black students often lack institutional support and funding, she said.

“Most Black students need a loan to survive,” Williams said. “We don’t own a home in my family structure. And so there’s no equity I can pull out on. There’s no family home I can live at. I was forced to live in a dorm, I was forced to live in an apartment, and I was forced to get a loan to be able to do it.”

Fulfilling Biden’s commitment to make payments more manageable for borrowers, the Department of Education also announced a revised payment system in January that will adjust expected loan payments to account for individuals’ incomes. But Williams said that even if payments are lowered, these expectations still do not take into account the realities that marginalized communities particularly face, such as the rising costs of food, rent and health care.

While Biden’s decision remains in legal battles, both Williams and Grace said it would still be only a first step, rather than a solution, to addressing student loan debt.

Grace said she is optimistic about the upcoming Supreme Court case, adding that she plans to keep trying to earn a master’s degree.

However, Williams said loan forgiveness continues to feel like a distant prospect and one that might never happen.

“It’s been so long, and I’ve lost that optimism. … I think it’s gone,” she said. “If it happens, great. If it doesn’t, my hopes aren’t high.”