Art exhibit review: ‘Exploring the Alps’ expresses wide range of mediums but fails to reach its peak

The gelatin silver print “Matterhorn from the North” is possibly the work of Aimé Civiale and is thought to have been taken between 1890 and 1893. The 40.3 by 59 centimeter piece is one of several artworks featured in the “Exploring the Alps” exhibition at the Getty Center, which will run through April 27, 2025. (Courtesy of the Getty Museum)

"Exploring the Alps"

Various Artists

Getty Center

Nov. 12 - Apr. 27

By Barnett Salle-Widelock

Nov. 13, 2024 10:32 p.m.

This post was updated Dec. 4 at 9:21 p.m.

The Getty Center’s look at an iconic mountain range presents a clever historical angle but leaves something to be desired.

“Exploring the Alps” opened Tuesday at the Los Angeles art museum and will be on show until April 27. The exhibit focuses on 19th-century depictions of one of the world’s most iconic mountain ranges, centering around a pastel by the Italian painter Giovanni Segantini. Intermixing photographs with pen and watercolor works, the display captures the fantastic beauty of the Alps from every angle.

Tucked away in a single room on the far side of the museum, the exhibition is unassuming in contrast with the dramatic, eye-catching nature of the mountainous subjects it presents. Less than a dozen works fit into the relatively small space. What does fit, however, is an immersive sense of quiet, which – combined with the exhibition’s mild lighting – successfully emulates the total peace one can only find in nature.

[Related: Art exhibit preview: Fall installments focus on themes including history, society]

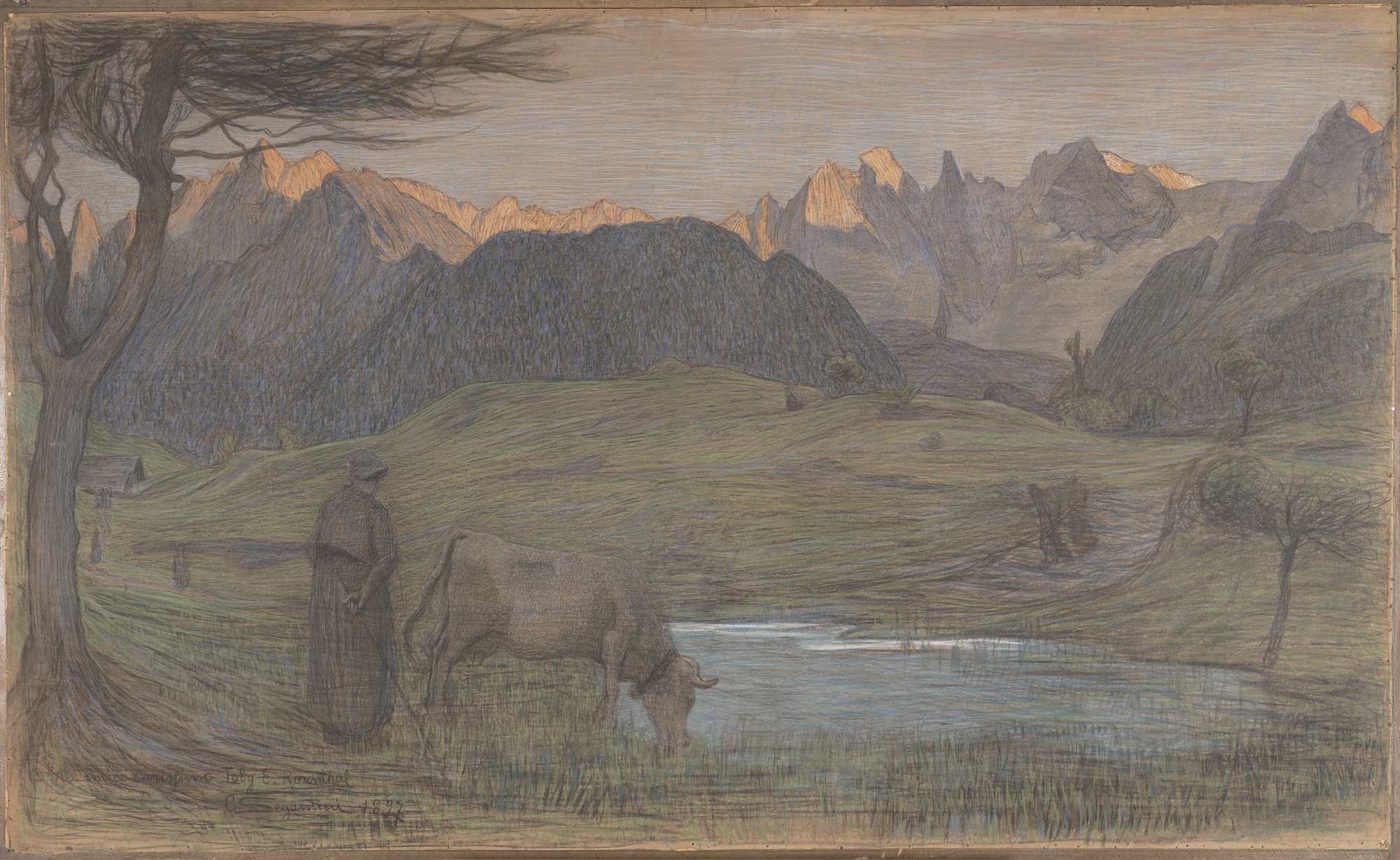

Front and center as the largest piece in the room is Segantini’s 1897 creation “Study for ‘La Vita,’” which depicts a panoramic view of a classic pastoral alpine scene in pastel, chalk, crayon and charcoal. Villagers and a cow sit peacefully beneath the shadow of the mountains, which span the frame as they are bathed in the light of a rising sun. A lake in the foreground completes the composition, mirroring the blue of the sky far above and giving the viewer a direct point of interest to focus on.

“Study for ‘La Vita’” is the exhibit’s least representational work, with the soft and quick lines showing the scene of the Alps as perhaps they would be seen in a dream rather than in precise detail. This ethereal presentation makes sense, as the painting was a study for a piece commissioned as a showcase of Swiss beauty, intended to be shown at the 1900 World’s Fair in Paris as part of a triptych. While Segantini died before witnessing the showing of his masterwork, “La Vita” featured alongside two other works, “La Natura” and “La Mort,” in the Segantini Museum in Saint-Moritz, Switzerland.

Other works take an opposite approach to depicting the Alps. While Segantini’s piece is one of the later offerings, it feels spiritually older in contrast with the comparatively modern approach of some of the other pieces in the collection. The 19th century was a time of change in the arts and sciences, and the “Exploring the Alps” exhibit captures this spirit of development through the dichotomy of mediums presented – including silver prints, ink and watercolor.

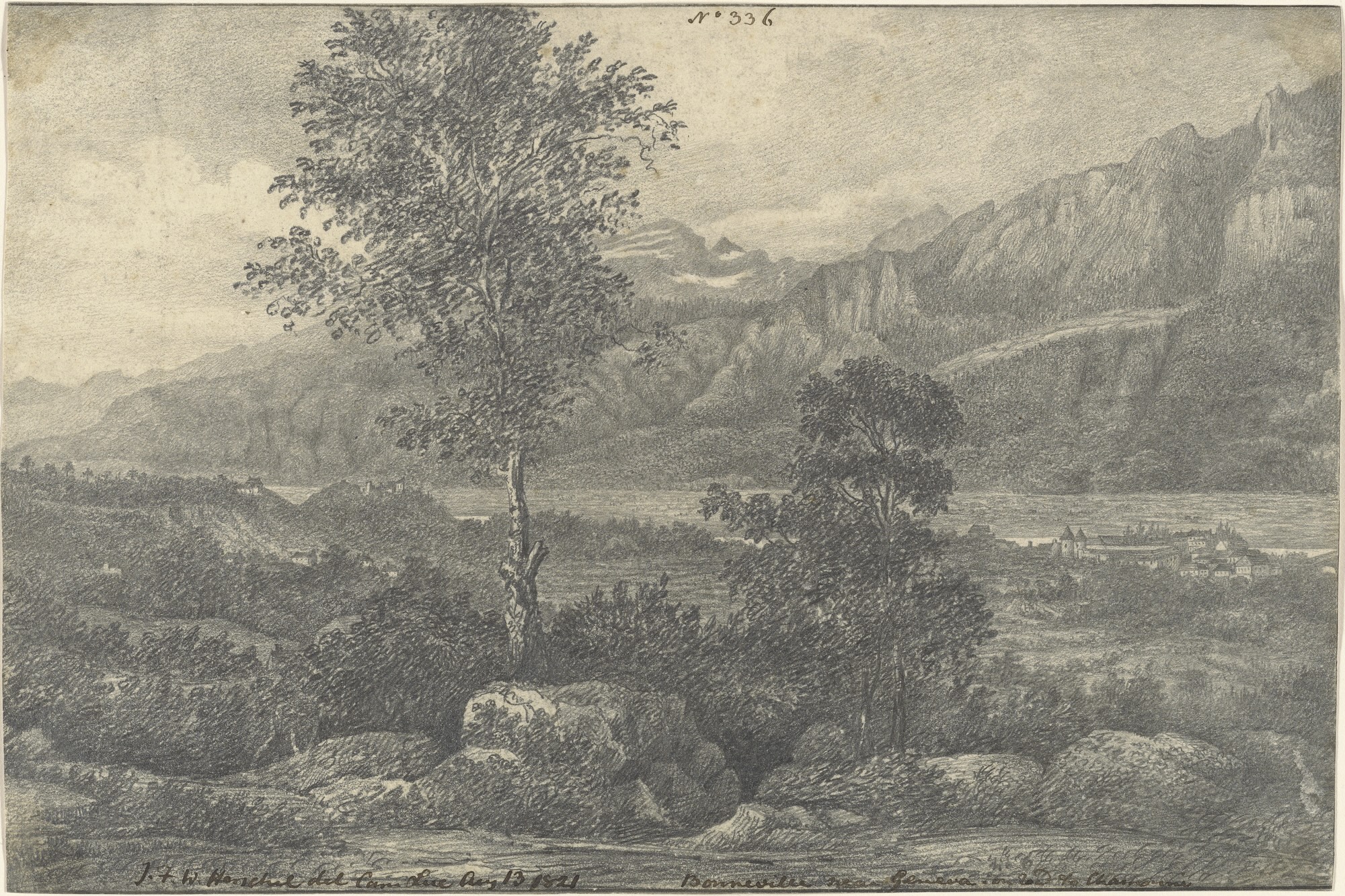

“Bonneville near Geneva on the Road to Chamonix,” an 1821 work by Sir John Frederick William Herschel, points to these shifting methods. Five years before the first photograph was taken, Herschel used a camera lucida – an early optical drawing aid – to illustrate a masterfully detailed scene of a far off village resting alongside a river under the rising mountains in smooth graphite.

With a fad of exploration sweeping through Europe in this era, photographs from the mountains at the time capture this spirit of rugged learning. The Bisson Frères’ 1860 image, “Ascent of Mont Blanc,” showcases a group of figures dwarfed by their surroundings as they lug heavy camera equipment up sharp, rocky terrain. Taken from above in albumen silver print, an early photographic technique, the Bisson Frères would have already had to drag their own gear hundreds of feet up the slopes to take their dramatic still of the scene.

The theme of the blurry border between science and art, as well as photograph and painting permeates the exhibit. In this case, it is the photographs that win. Thomas Ender’s “Wooded River Landscape in the Alps” from the mid-19th century is a colorful, romantic painting of an idyllic, clear day in a valley. With all its soft peacefulness, it still falls short of the dominant, imposing beauty of a simple shot of the iconic Matterhorn – thought to be by Aimé Civiale – in black, white and gray.

The strength of the photographs relative to art from other mediums is predominantly because a mountain range such as the Alps feels like it was made for a camera. The snowcapped peaks are striking in their own right, and the believability of a photograph overwhelms any twist that could be imparted by a paintbrush. Ender’s watercolor provokes a beauty of small proportions, but it takes a print image to truly capture the stunning scale of the landscape.

What all mediums featured in “Exploring the Alps” demonstrate, however, is the powerful draw of the range. Segantini, like many alpine painters, worked en plein air – or outdoors with his easel – as he drew the scene in front of his eyes. Just like the photographers trekking across unfriendly ground for the sake of documenting the stunning surroundings, painters worked in uncomfortable conditions outside the studio, all out of a love for the scenery.

[Related: Alumnus’s dance company probes surveillance through choreographing the unseen]

While the exhibit features excellent works, the size of the “Exploring the Alps” display is disappointingly small. The massive body of work that the Alps have inspired over the last few centuries feels distant, replaced by a collection of unexceptional size. It would seem appropriate to feature more works that can be measured in feet, such as Segantini’s, but instead most could be measured in inches, contrasting with the enormous mountains they show.

The most striking image, the photograph of the Matterhorn, is the second largest, and not by chance. It grabs attention from across the room, just as the mountain in real life does over its surrounding landscape. Unfortunately, the entire exhibit does not have that same attention-grabbing effect. If one is willing to look closely, there are interesting scenes on display, but a sparse arrangement takes away from some of that beauty.

Ultimately, “Exploring the Alps” is a wonderful taste of the mountains, but the exhibit’s limited scope leaves the viewer hungry for more.