UCLA School of Law project researches restrictions on critical race theory

By Anna Feng

Oct. 18, 2022 11:57 p.m.

This post was updated Jan. 28 at 4:12 p.m.

A UCLA School of Law research project aims to analyze restrictions on critical race theory, which has sparked controversy in local school districts and K-12 classrooms across the country.

LaToya Baldwin Clark, an assistant professor at the School of Law, defines critical race theory as an academic and legal lens of looking at the law and governmental institutions to understand why racial inequality persists in light of civil rights successes. Although critical race theory is mainly taught in law schools, many of the restrictions placed upon it have been on its usage in the K-12 classroom, in which critical race theory is rarely taught as critical race theory at all, she said.

“That doesn’t mean that we are going to students … and saying, ‘Hey, race is everywhere; everything is racist,’” Baldwin Clark said. “That’s not at all what teaching CRT in schools would be, but it is about teaching a way of critically looking at our institutions and recognizing that many of them are quite flawed if what we care about is racial justice.”

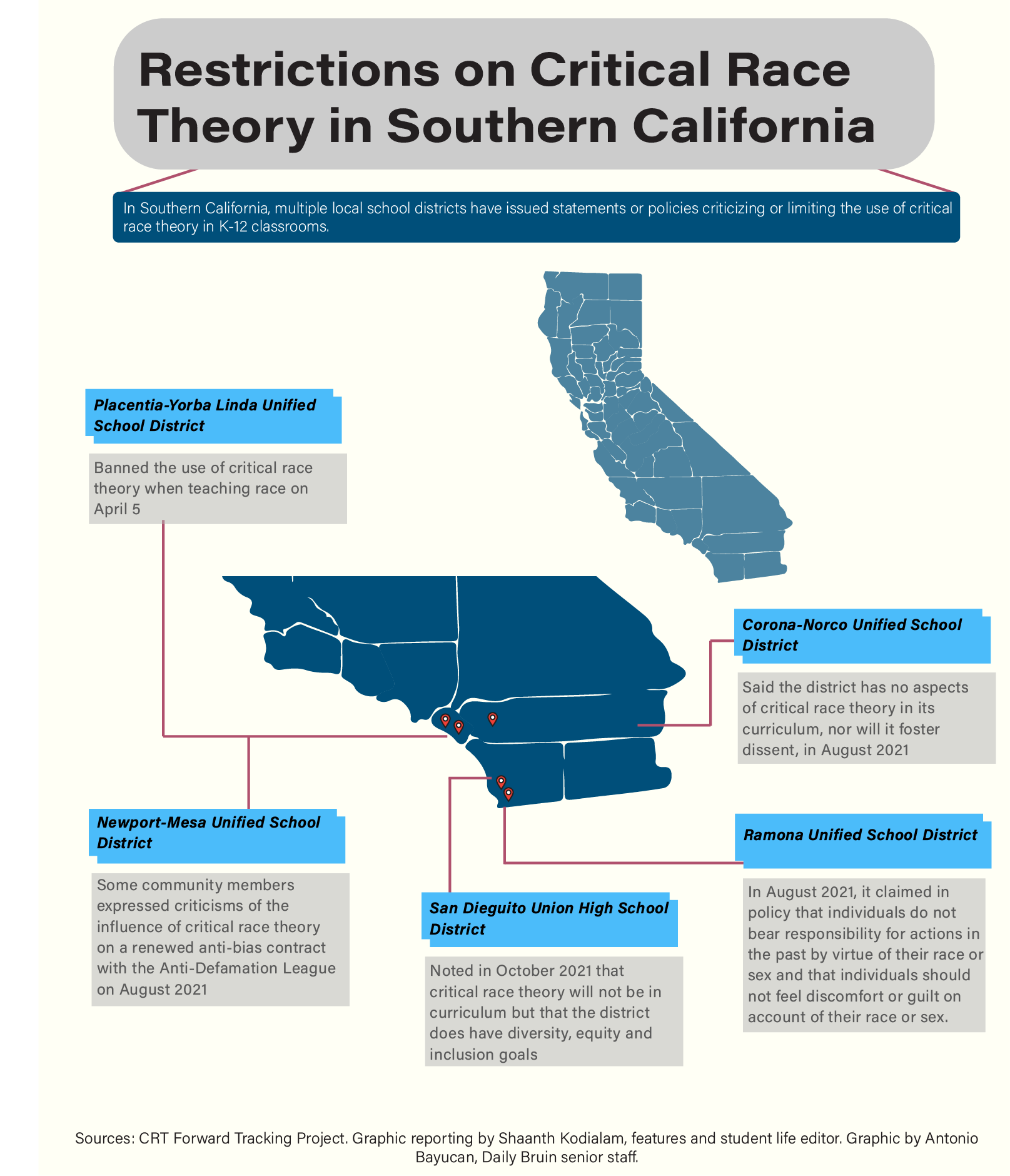

In recent years, critical race theory has become a contentious topic in American politics, said CRT Forward Project Director Taifha Alexander. Seven California school boards introduced eight regulations – including policies and resolutions – restricting or criticizing the use of critical race theory since 2021, and six of them were adopted, according to the CRT Forward Tracking Project.

The School of Law’s CRT Forward Tracking Project aims to provide a comprehensive analysis of restrictions on critical race theory in the U.S. so academics, lawyers, teachers and parents can understand the similarities between different criticisms of critical race theory, Alexander said.

Alexander, who is also a School of Law alumnus, said CRT Forward uses key phrases such as “1619 project” and “resolution” to comb through legal databases and identify cases of anti-critical race theory activity. The research team then pinpoints the entity that is being targeted, such as K-12 schools or inclusion policies, and the information is then logged into their own research database, she added. This data collection culminates in an interactive map display of anti-critical race theory activity across the U.S.

Alexander said she believes the backlash critical race theory has received is in response to the protests for racial justice in 2020 following the death of George Floyd.

“All of the momentum … ensuring that we were able to reach our full potential as a multiracial democracy was curbed because conservative activists and anti-CRT architects didn’t want the world to challenge the current status quo,” Alexander said.

For CRT Forward research assistant and law student Nicole Powell, one of the main takeaways from working on the project was seeing the breadth of the legislative attacks on critical race theory.

“It’s not necessarily attacking what (people) think is critical race theory,” Powell said. “It’s just creating a boogeyman of critical race theory and monitoring and surveilling classrooms.”

Alexander said the CRT Forward project examines state and federal activity alongside nonlegislative activity, such as training restrictions, setting it apart from other projects tracking restrictions on critical race theory. As a result, it provides a more comprehensive view of the anti-critical race theory measures currently taking place in the U.S., Alexander added.

Law and public policy graduate student Danielle Garcia, who also worked on the project as a research assistant, said the project’s comprehensive view of the anti-critical race theory measures in the U.S. was particularly shocking to her because of how pervasive it was.

“It almost felt like you could not run for school board in some of these towns without taking a side on CRT,” Garcia said. “They were disassociating with CRT because of how much of a trigger word it was and what a brand it cultivated.”

Another thing that surprised Garcia in the project findings was seeing how extreme anti-critical race theory activity was, Garcia said. She pointed to one restriction attempting to rename the enslavement of Black people as forced migration.

Fatima Rivera, a fourth-year sociology student and CRT Forward research assistant, said many parents might be worried that teaching about race in the classroom may create feelings of guilt for some students. She added, however, that she wished anti-critical race theory activists would consider the perspectives of people of color.

“I know that a lot of them become very offended because they think that they’re placing blame on their race or they’re making their children feel guilty for belonging in that race,” Rivera said. “But … for people of color, this is their whole lives. It’s not something they can just censor themselves from.”

Contributing reports by Shaanth Kodialam, features and student life editor.