Examining how school zoning regulations contribute to socioeconomic disparities

By Riya Abiram

March 14, 2024 11:59 p.m.

This post was updated April 1 at 11:48 a.m.

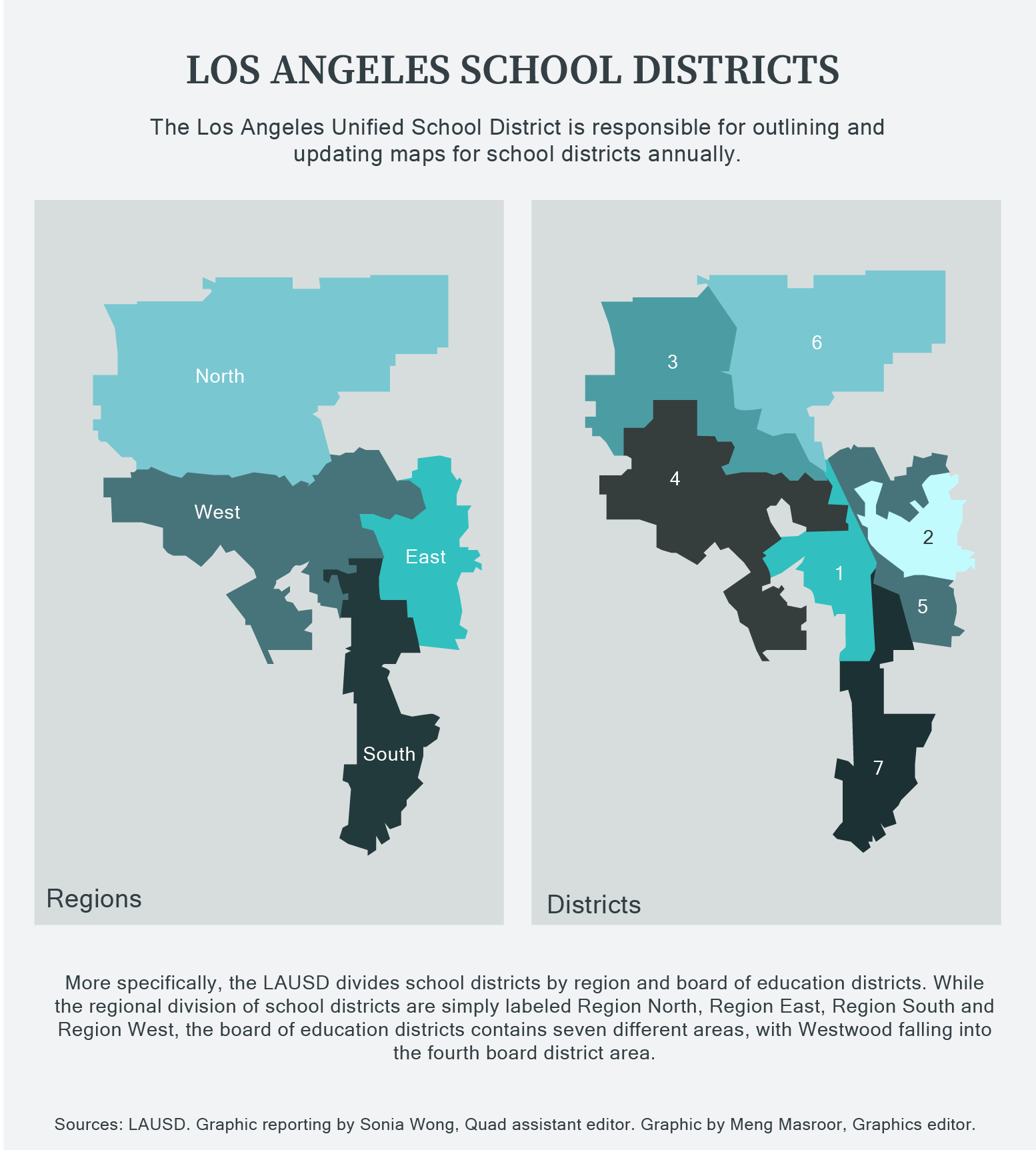

Across the country, the intricacies of school district zoning laws and district-drawn attendance zones that determine who can attend certain public schools extend beyond the physical layout of neighborhoods, according to the Urban Institute and Education Next.

School zoning regulations serve to provide students with a specific school depending on their attendance zone, according to the California Department of Education and the United States Congress. However, some experts and state officials believe these procedures uphold an archaic system that perpetuates historical inequalities and reinforces socioeconomic disparities.

School district legislation began as an approach to ending systemic educational inequalities, according to Education Next. In 1974, Congress passed the Equal Educational Opportunities Act, which states that public school students are entitled to the same educational opportunities regardless of sex, race, national origin or color.

The act also states that one’s neighborhood is the appropriate basis for determining public school assignments.

Critics argue that while the law may appear promising on paper, it still may be insufficient in terms of attaining complete educational equality. For example, according to Education Next, the endorsement of neighborhood-based assignments kept segregated neighborhoods from many educational opportunities. The same source stated that prior to the passage of Proposition 13 in California in 1978, the vast majority of funding for public schools came from neighborhood property taxes, which allowed affluent communities to provide more resources for their students than those in school zones with lower property values.

The laws surrounding school district zoning continued to evolve throughout the country. Proposition 13 aimed to reduce the impact of property taxes on public amenities such as schools by capping overall property tax rates and giving the state legislature the power to allocate funding for various school districts, according to the California Legislative Analyst’s Office.

Despite these initiatives, many remain unsatisfied with school zoning policy. Scott Epstein, the director of policy and research at Abundant Housing LA – which is a nonprofit organization focused on improving housing access in the greater Los Angeles area – said there is much progress to be made in terms of building inclusive and equitable communities.

“We basically have given up on the housing side,” Epstein said. “American policy when it comes to desegregating our schools has focused on transportation, has focused on the schools themselves, and not desegregating neighborhoods. That’s a huge problem because the neighborhood piece is the root cause of the problem.”

Additionally, while Proposition 13 decreased the funding disparities between schools in higher- and lower-income neighborhoods by enforcing an annual cap, the property tax revenue generated within wealthier communities remains substantial compared to that in areas with lower property values, according to the California School Boards Association.

With this difference in mind, a handful of initiatives have been introduced in the state. For example, Proposition 98, which was passed in 1988, guarantees an annual increase in education spending in the state budget and sets a minimum funding requirement for all community colleges and public schools in California.

When looking at the neighborhoods surrounding UCLA, Epstein said housing analysts believe disparities extend into the school’s surroundings, such as the wealthy neighborhood of Holmby Hills located to the east of campus. Epstein added that these disparities stem from policymakers aiming to segregate affluent communities from lower-income populations.

“City leaders made a choice about how to zone that neighborhood (Holmby Hills). Most of those original choices quite frankly were built on racial animus and exclusion,” Epstein said. “That is the history of Los Angeles, and generations of leaders since then have made the choice to retain that exclusionary map.”

These distinct zoning practices have been linked to a child’s readiness for school and overall childhood development, according to Frontiers in Education. Lower spending and fewer resources in a school district can result in a higher likelihood of grade repetition, suspensions and expulsions, as well as decrease the likelihood of students graduating from high school and being ready for college, according to the Learning Policy Institute.

Epstein added that these policies can contribute to educational disparities.

“We have certain laws around educational equity, but the truth of the matter is that even in our public school system, schools that are in more affluent areas have a lot of advantages,” Epstein said. “They have parent-teacher associations that are connected to more resources. Often, the parents in those neighborhoods have more time to volunteer. So this plays out in terms of students’ opportunities.”

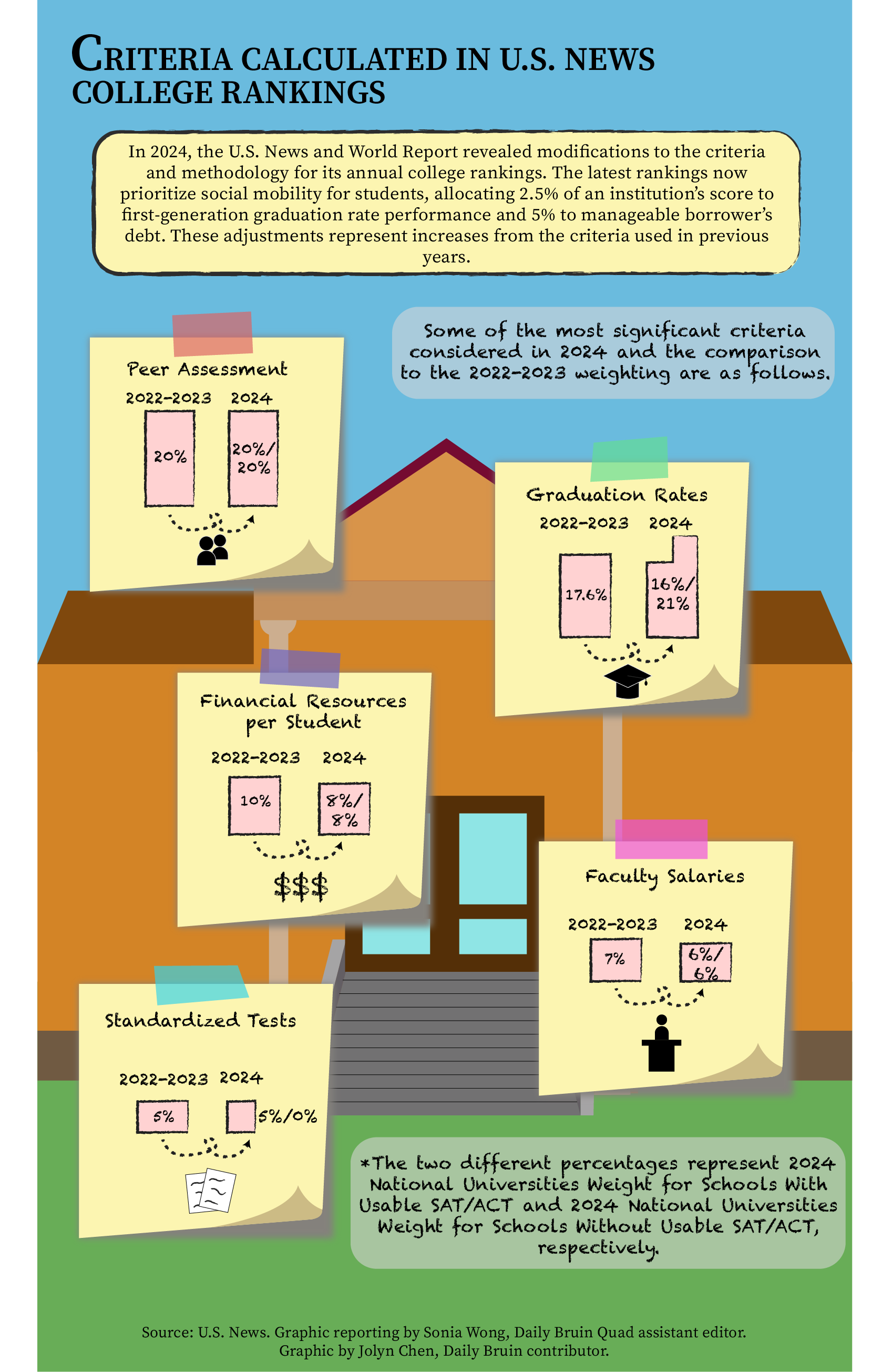

According to U.S. News & World Report, studies have found that students attending more affluent schools have access to a wide array of extracurriculars and advanced courses as well as better teachers, and they have an easier time attaining higher GPAs, all of which affect graduation rates and college admissions.

Charvi Reddy, the president of Advancing Childhood Curiosity to Empower STEM Scholars – which is a club aimed at providing quality STEM education to underserved schools in the LA area – said she notices substantial educational gaps that arise in less affluent communities.

“If you’re living in an area where your parents are trying to make rent every month, they’re focused on that. They’re focused on trying to feed their kids with whatever’s left. You’re not going to have the opportunities that kids in wealthier areas have,” said Reddy, who is also a fourth-year human biology and society student. “You’re not going to go home and have a parent or even a paid tutor who helps you with your homework – you’re most likely going to be figuring it out yourself.”

Sana Minhas, a third-year human biology and society and international development studies student, said she attended a high school in Fresno with fewer resources than a nearby well-funded counterpart. She added that her experience applying to universities highlighted the challenges that come with fewer resources and opportunities.

“In UC admissions, you have to be a bit competitive. A lot of colleges want to see that you have extracurriculars. They want to see that you have volunteer hours. They want to see what kinds of clubs you’ve been in,” Minhas said. “While I’m sure a lot of schools might understand that some schools don’t have the funding and a lot of students don’t have the access to be a part of clubs, it’s still a big issue. If you don’t have these opportunities, you might feel like you can’t apply in general.”

Minhas added that it was difficult for her and her classmates to receive numerous rejections, as she thinks the lack of opportunities in high school affected their college decisions.

“They are such smart, intelligent, talented people, but I do feel like a bit of the opportunities we had impacted our admissions,” Minhas said.

For students from underprivileged backgrounds who obtained admission to higher education, other obstacles exist. Students from low-income families who attend college are 10.5 times more likely to drop out than their high-income counterparts, and they experience a lack of guidance and support during their higher education journeys, according to Educational Partnerships Inc.

Epstein said most affordable housing is built in lower-income areas that are less adjacent to jobs, services and often educational opportunities.

Recognizing these challenges, Epstein said there are key initiatives on the 2024 November ballot that Bruins should look out for in improving regional equality, such as a measure that would increase funding for affordable housing through sales taxes as well as a measure called Healthy Streets, which would force the city to completely implement its public transportation plan.

“Even when the streets are being repaved, it would be a great opportunity to do those quite cheap and very impactful changes to the design of the street to make them more sustainable and equitable,” Epstein said.