UCLA study finds variance in certain cells affects immune responses between sexes

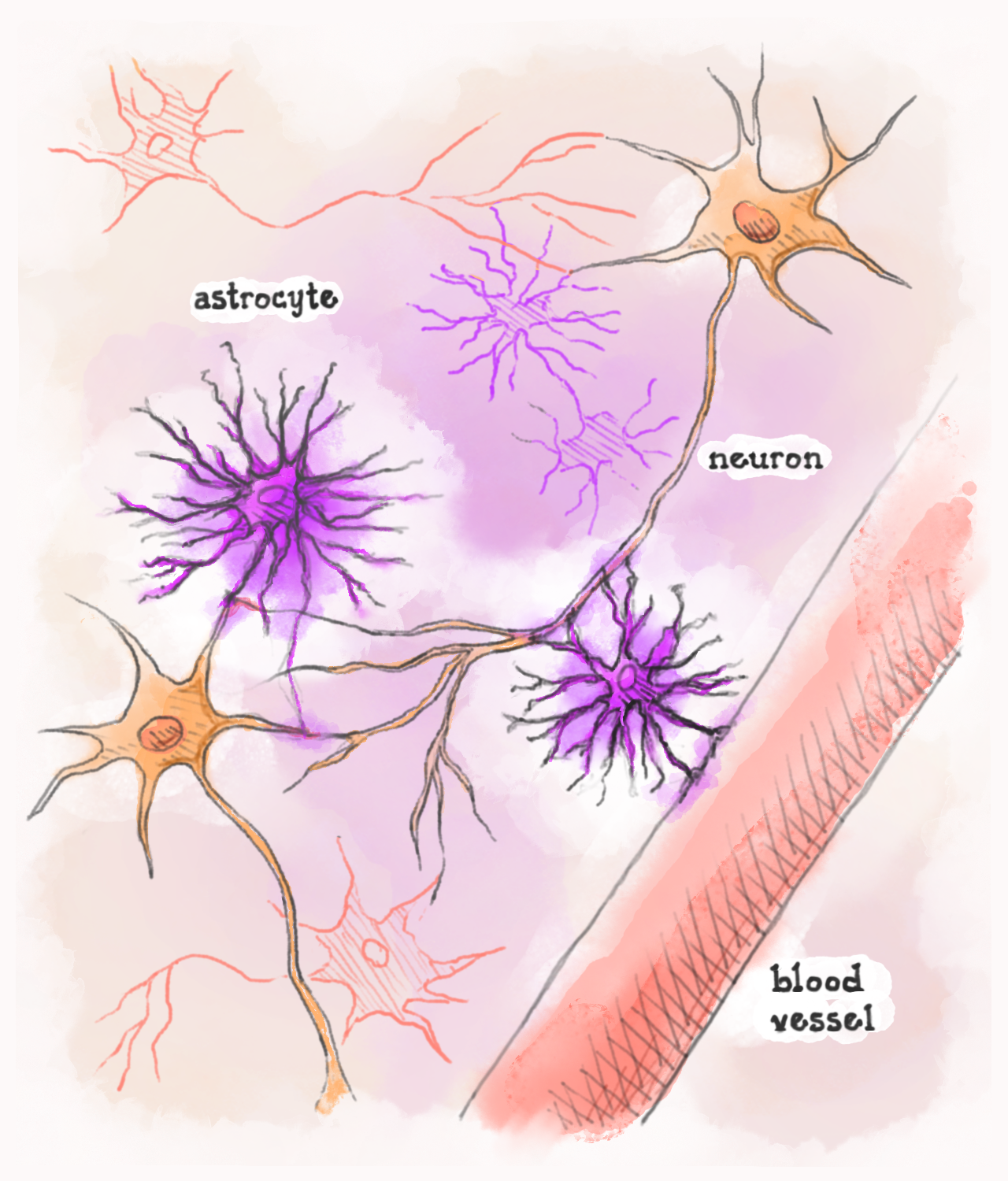

Alston Kao/Daily Bruin

By Megan McCallister

May 21, 2023 10:48 p.m.

Differences in immune cells between sexes allow biological females to have stronger immune responses in early stages of infection, according to a UCLA study published in March.

The immune system’s first responders after a person is infected by a virus are called natural killer cells, said Joey Li, a medical and molecular biology doctoral student. He added that men have more of these cells than women despite being more susceptible to viral infections.

The study’s researchers found that the weaker natural killer cells found in males may result from a deficiency in a protein called UTX, which is coded for by a gene located on the X chromosome, Li said. The UTX protein plays a critical role in fending off viruses and tumor invasions, said Mandy Cheng, the first author of the study.

Typically, biological females have two X chromosomes whereas males have one X and one Y chromosome, said Cheng, a postdoctoral researcher in molecular and cellular biology. As a result, female natural killer cells have two copies of the gene that codes for the UTX protein, while males have just one, she added.

The researchers found that natural killer cells which had two copies of the gene were able to fight off viruses more efficiently than cells with only one, Cheng said. These results indicate that the higher amount of UTX found in female natural killer cells, as compared to male ones, might be what allows the female immune system to better attack viral invaders, she added.

“The main goal here is to raise awareness into how big of a difference there is between … female and male immune systems and how a lot of our therapies are mainly catered towards males at this moment,” Cheng said.

The authors said these differences might have consequences for future research. Historically, most studies were conducted on male animals because scientific belief held that they were easier and cheaper to study than female animals, said Arthur Arnold, a distinguished professor of integrative biology and physiology and a co-author of the study.

“It turns out that’s basically quite flawed because males and females are different in many ways,” Arnold said. “The risk is, if you only study males all the time, then the principles you learn might only apply to males, and you don’t really know when they also apply to females.”

To confirm that the different immune responses could not be attributed to any hormonal differences between sexes, the researchers replicated the study in mice that had sex-hormone-producing organs removed and found that female mice still had stronger immune responses, said Timothy O’Sullivan, senior author on the study.

This evidence adds to a growing body of research demonstrating that male and female cells are intrinsically different, not just because of hormones, Arnold said.

Li said the report’s insights may have clinical implications for individuals undergoing gender-affirming hormone therapy.

“These kinds of studies will help us remain cognizant clinically of that, ‘OK, this patient may have altered immune function,’” Li said.

A deeper understanding of the differences between male and female natural killer cells can also help with developing better immunotherapy treatments for cancer, O’Sullivan said. O’Sullivan, an assistant professor of microbiology, immunology and molecular genetics, said he studies how these cells can be engineered to fight severe viral infection or tumors. The study’s findings might help in developing methods to use female natural killer cells as potential immunotherapeutic agents, he added.

The results of the study could also partially explain why males tend to be more susceptible to severe COVID-19 infection and why females generally respond better to COVID-19 vaccinations, Li said.

Ultimately, understanding sex differences is an important step toward more personalized medicine, Cheng said.

“(This study is) helping us understand the mechanistic biological reasons for these sex differences that we see in outcomes of viral infection,” Li said. “I think it’s really important because it allows us to account for that clinically when caring for patients.”