UCLA study finds that some neurological cells may affect Alzheimer’s disease

(Megan Wu/Daily Bruin)

By Leila Okahata

Nov. 14, 2022 12:07 a.m.

This post was updated Nov. 17 at 7:17 p.m.

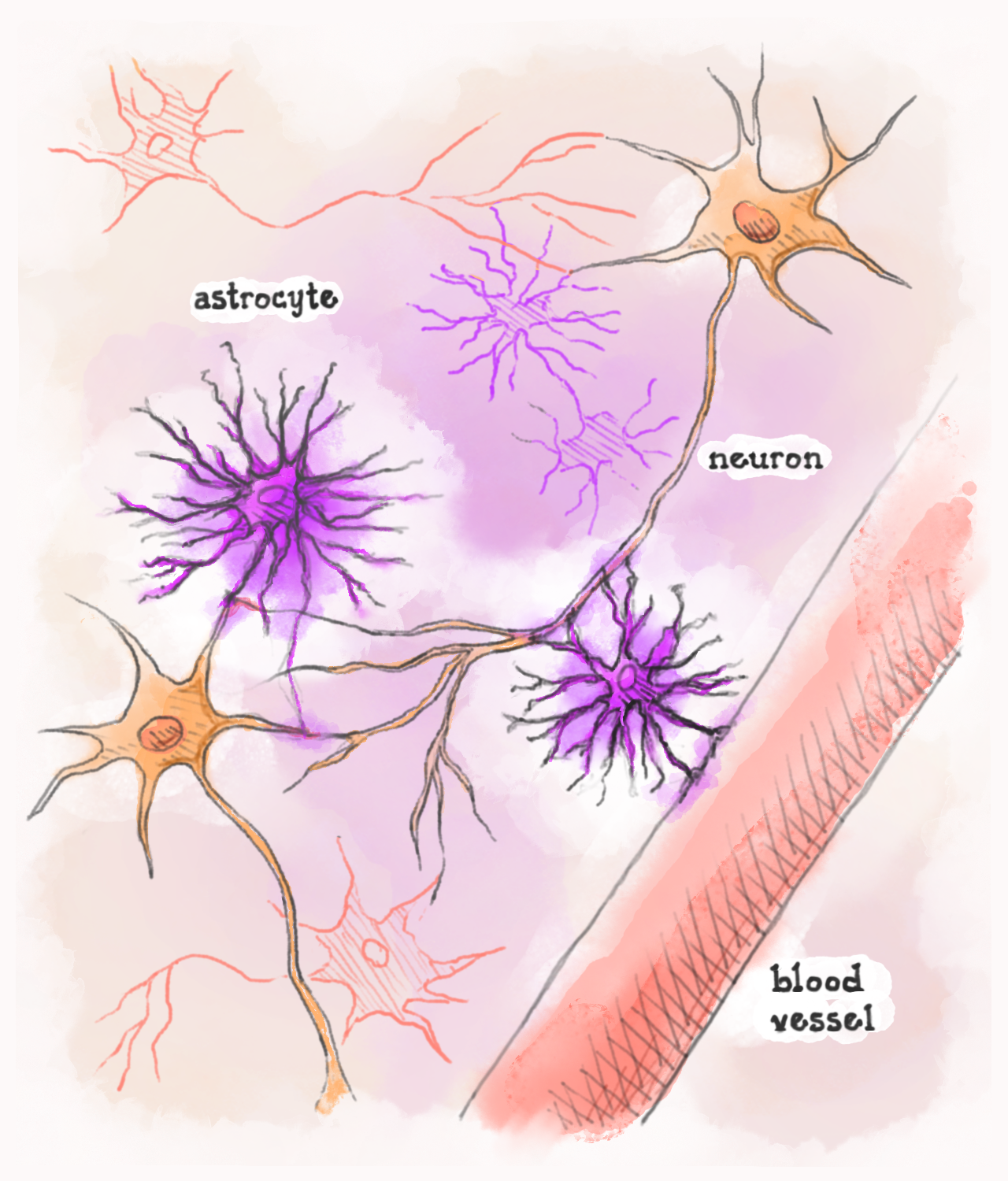

A recent UCLA study found that astrocytes, star-shaped cells in the brain, may play a role in Alzheimer’s disease progression and be a potential target for future therapies.

According to Baljit Khakh, a senior author of the study published Nov. 4 and a professor in the departments of neurobiology and physiology, astrocytes are a relatively understudied cell type. He said his initial motivation for the project was to better understand their structure and distribution across the brain. However, as he and his team were analyzing the genes that underlie these cells’ complex, bushy structure within mouse brains, they unexpectedly found a subset of genes related to increased risk of Alzheimer’s disease, he said.

“This doesn’t often happen in science,” Khakh said. “But it illustrates that having an open mind and asking basic questions is still a good way to discovery.”

This finding led the team to wonder if astrocytes’ structure might be altered in Alzheimer’s disease, Khakh said. To test this hypothesis, researchers turned off the genes related to astrocytes’ bushy shape, making them structurally smaller and simpler, in a part of the brain known as the hippocampus, said Fumito Endo, lead author of the study and an associate project scientist in Khakh’s lab. According to the study, the mice displayed cognitive impairments and performed poorly on memory tests as a result of the change.

The team also examined the genetic data of astrocytes in human brains afflicted with Alzheimer’s disease and found that the same genes associated with complex astrocyte structures were not expressed, while the genes associated with simple astrocyte structures were, Khakh said.

Although these results imply that astrocytes are potential factors in Alzheimer’s disease, it is unknown whether the transition to simpler cell shapes for astrocytes is a cause of Alzheimer’s disease or a symptom of it, Khakh said. These findings further illustrate the complexity of Alzheimer’s disease as, according to the Alzheimer’s Association, the onset and progression of the disease may not have a singular cause.

“In complex brain diseases like Alzheimer’s, it’s very simplistic to think of them as affecting one cell type, either the neurons, astrocytes, microglia, or blood vessels,” Khakh said. “It’s likely that they affect all of these cell types and, at some point, those of us who are interested in the field will have to converge and start treating them as multicellular diseases.”

Nevertheless, with further research, restoring astrocyte shapes may be a beneficial treatment for not only Alzheimer’s disease, but also other central nervous system disorders such as Huntington’s disease and multiple sclerosis, Endo said. Astrocytes could be similarly smaller and simpler in these disorders, he added.

Astrocytes have traditionally been regarded as cells that simply attach neurons together, but advanced research has revealed these cells to be important for providing neurons with nutrients and aiding blood flow in the brain, Khakh said. To expand scientific understanding of astrocytes, this study also provides a dataset of the morphological and genetic features of astrocytes within 13 brain regions, he said.

Jessica Rexach, an assistant professor-in-residence of neurology, said this dataset will become an important tool for researchers in astrocyte biology for many years to come.

“This is really that resource … that we’ve been needing in the field,” she said. “And so quite concretely and quite practically, I will be using it for experiments that I’ve wanted to do but haven’t been able to because I haven’t had just the right datasets to do it with until now.”

Khakh said the researchers now have many new questions to answer about astrocytes and their role in the brain and body.

“We’re beginning to think that they may be active players in how the nervous system works and how it becomes dysfunctional in disease,” Khakh said. “Now, we don’t know exactly how this happens, we don’t know exactly how they contribute to functions of neurons, and we don’t know exactly how they change in disease, but that’s what we’re trying to do.”