UCLA researchers use artificial intelligence to provide data on overdose deaths

(By Isabella Lee/Illustrations Director)

By Caroline Sha

Sept. 2, 2022 9:11 p.m.

This post was updated Sept. 5 at 8:40 p.m.

UCLA researchers have created models using artificial learning that can be used to quickly identify the drugs involved in overdose deaths.

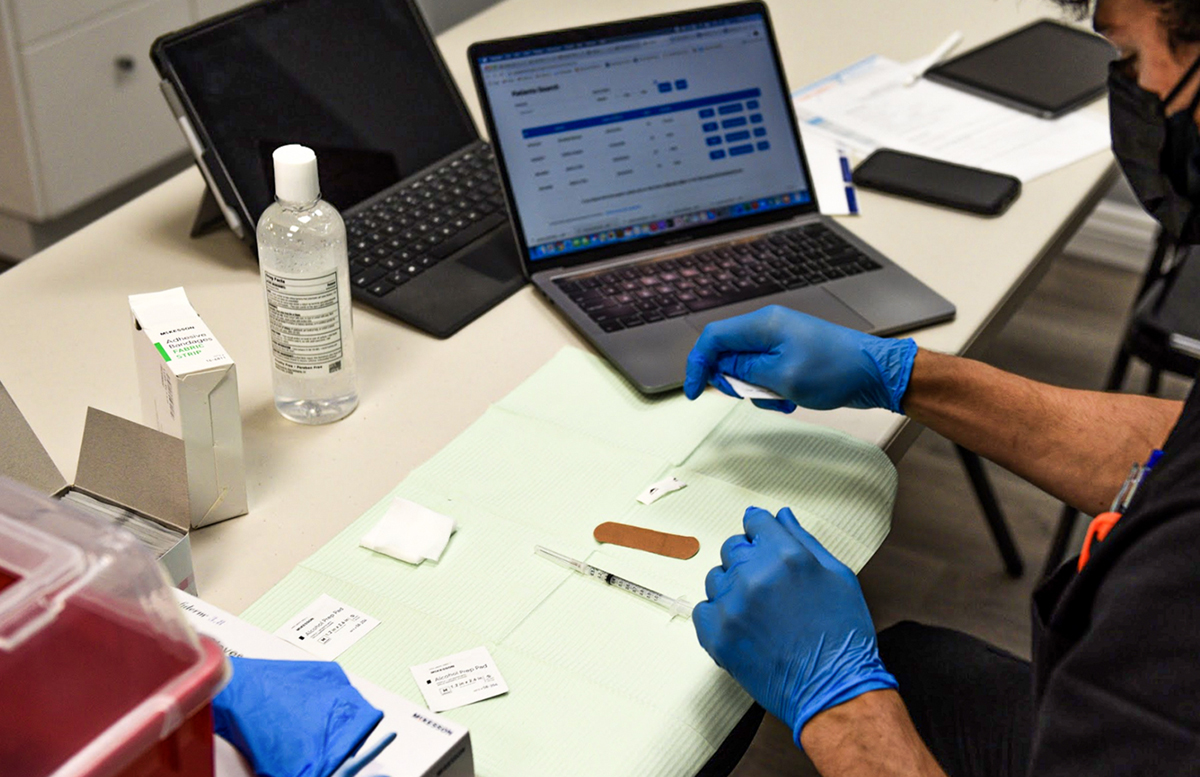

In the study published Aug. 8, the researchers found the algorithms tested had perfect or near-perfect accuracy in identifying the substances involved in overdose deaths, said David Goodman, assistant professor in the Division of Infectious Diseases, adding that the most commonly identified substance was fentanyl.

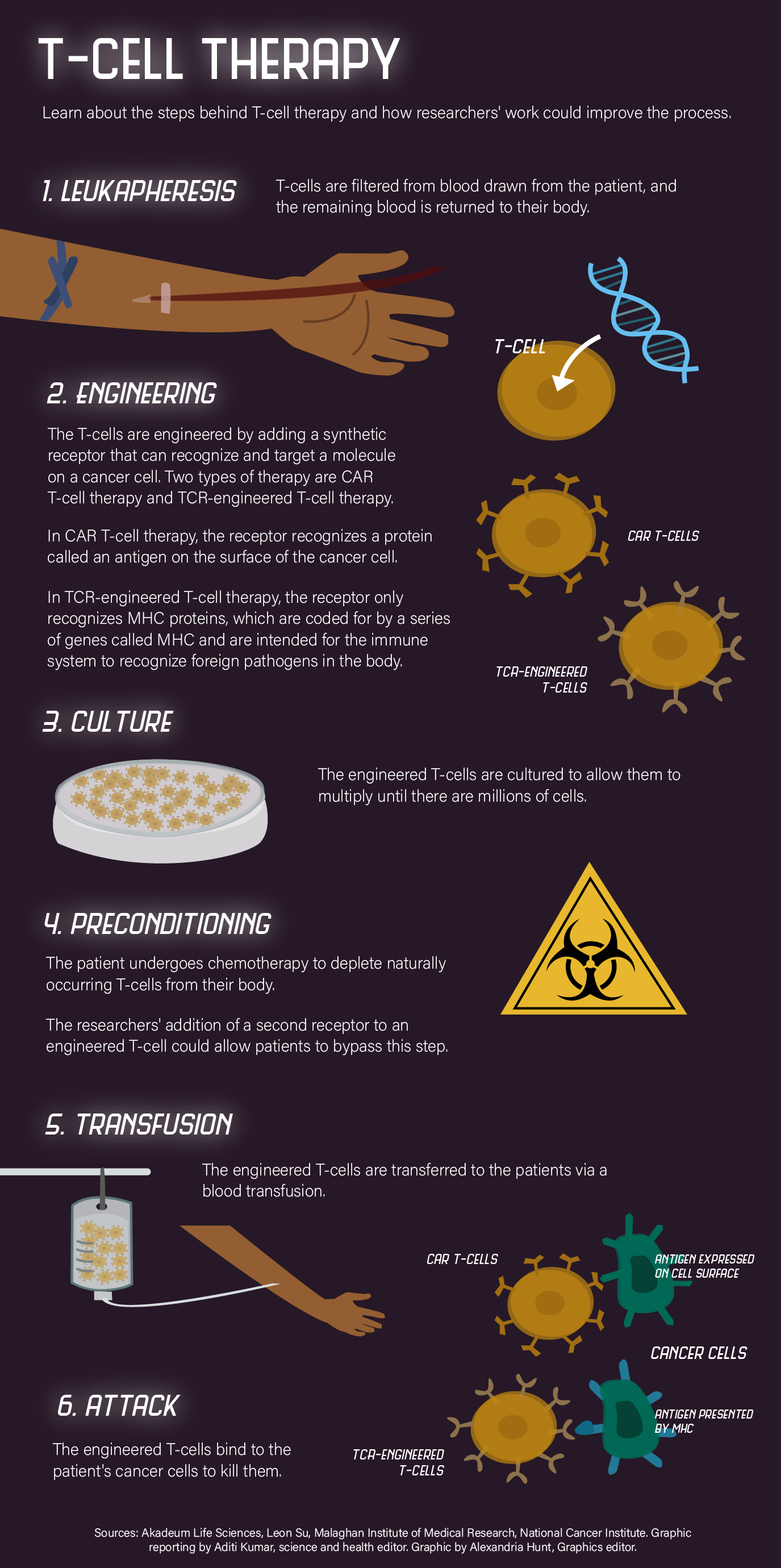

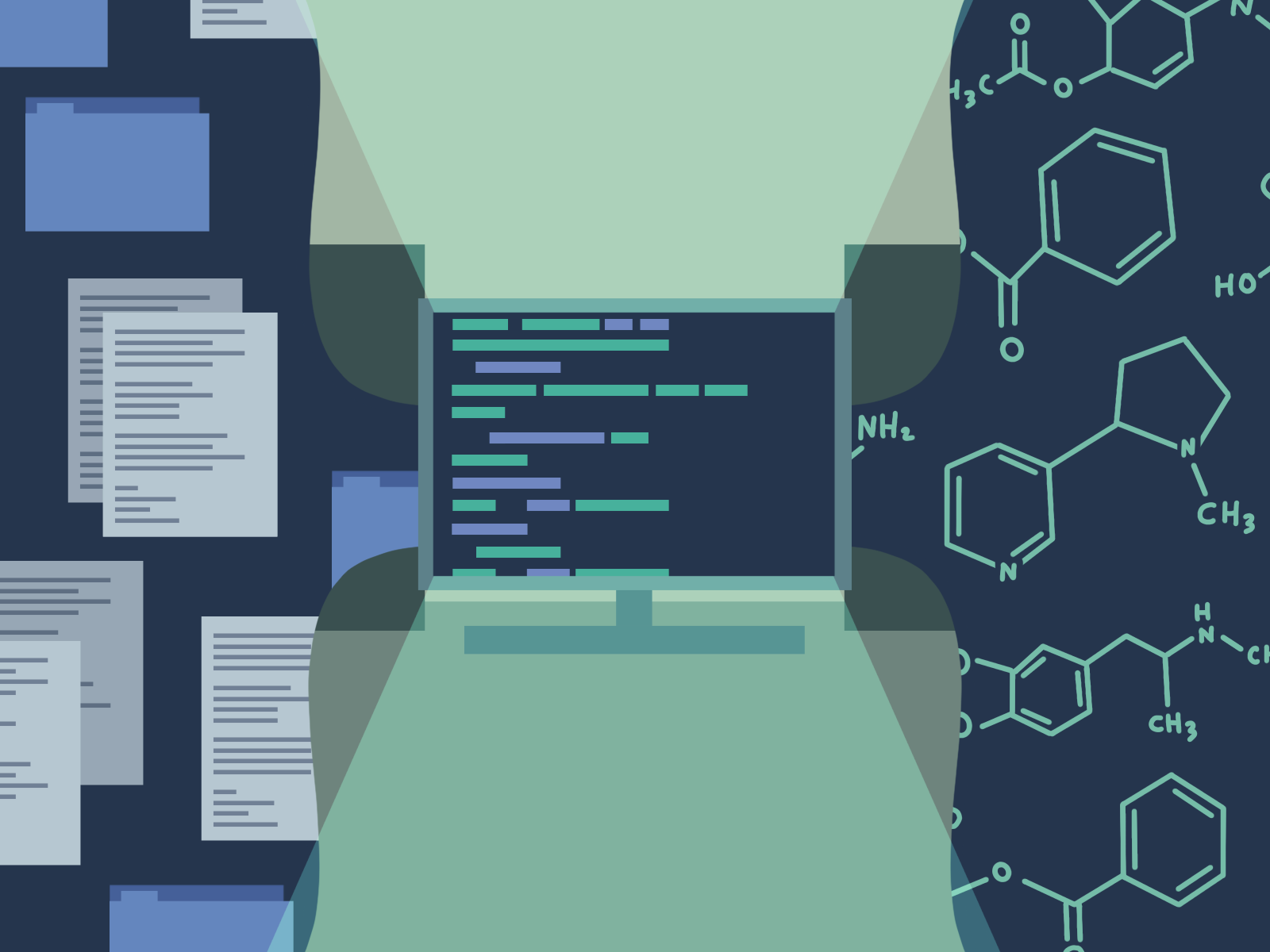

The researchers evaluated the accuracy of different machine learning and natural language processing models in identifying the substances involved in overdose deaths recorded in county and state medical examiner data, according to the study.

Both ML and NLP are forms of artificial intelligence, said Goodman, who is also a co-author of the study. He added that NLP allows computers to understand and interpret human language while ML uses data produced through NLP processes to create models.

The United States’ overdose rate has spiked during the COVID-19 pandemic and prior to the pandemic was around 20 times the global average, said Joseph Friedman, a substance use researcher in the UCLA department of social science.

[Related: UCLA study isolates monthly overdose statistics, reveals pandemic related surge]

However, it can take months for federal data on overdose deaths to become publicly available, Goodman said. A leading cause for this time discrepancy is that the current system for processing overdose deaths involves manual review by humans, he added.

Such lags can delay awareness of important patterns in this data, said Chelsea Shover, assistant professor in residence in the Division of General Internal Medicine and Health Services Research. Her team was able to document the spread of fentanyl to the West Coast before the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, though the agency has also become faster in the last two years, she added.

However, by using medical examiner data, the present lag could be reduced to two to three weeks, said Shover, who is another co-author of the study.

Expediting the drug identification process for overdose deaths allows researchers to work with public health agencies more efficiently to respond to overdose outbreaks, Friedman said.

The time saved by switching from manual review to AI can also allow public health agencies to do other analyses, such as examining the overdose rate in demographic groups, and enables researchers and officials to disseminate overdose data to the public quickly, Shover said. These analyses let them facilitate public health campaigns and inform health care providers and communities about the latest patterns in overdoses faster, she added.

Furthermore, NLP models allow for the analysis and classification of detailed data regarding overdose deaths, Goodman said.

He said researchers could train the model to differentiate between similar drugs such as fentanyl – an opioid – and buprenorphine – a medication used to treat opiate use disorder – which are both currently classified with the same code when creating national statistics, allowing communities and researchers to access more specific data regarding overdose deaths.

He added that the models could also be applied to segregate overdose data on a more local level, as the CDC only releases national- or state-level data.

Additionally, although the data used to build these models came from only three counties, the models performed well in other jurisdictions, Goodman said. He added that these models require an extensive amount of data on a drug, meaning the models may fare worse in the classification of drugs with less data.

The developed models are publicly available on Github, Shover said, adding that she’s willing to help specific agencies and jurisdictions adapt the models to their needs.

Goodman said he and Shover have also applied for a grant to create a more publicly oriented platform where they could provide local-level overdose data to communities.

“If public health agencies are connected with harm reduction organizations and community organizations, … they’re able to give them a heads up about kind of epidemiological findings that are coming down the pipe, and I think that’s the key thing,” Friedman said.