LA Day of Remembrance observes anniversary of incarceration of Japanese Americans

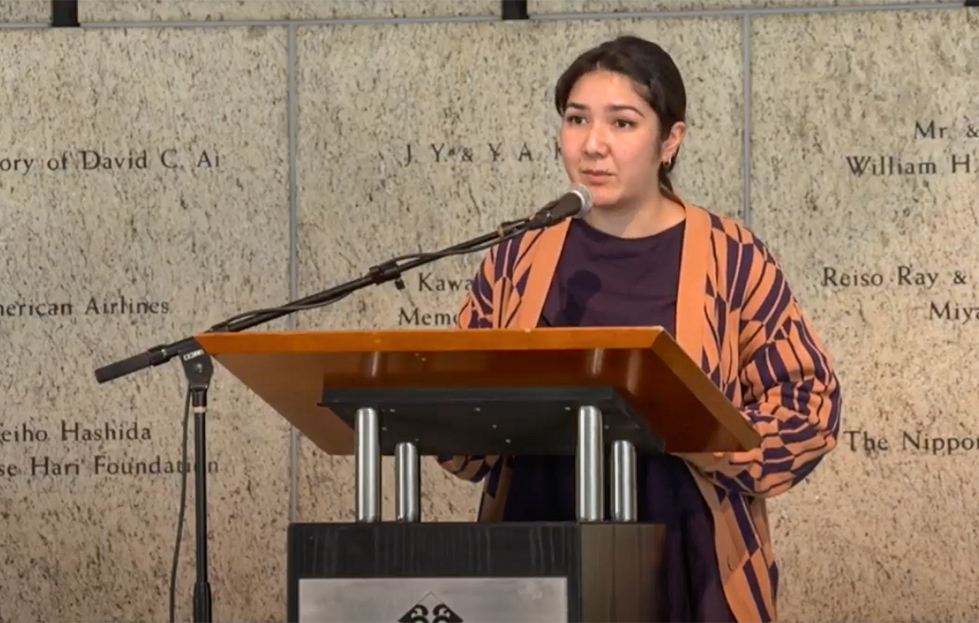

Panelists at the 2022 Los Angeles Day of Remembrance spoke about topics such as reparations. (Megan Tagami/Daily Bruin)

By Megan Tagami

Feb. 25, 2022 8:39 p.m.

This post was updated Feb. 28 at 12:09 a.m.

The UCLA Asian American Studies Center co-sponsored the annual Los Angeles Day of Remembrance on Saturday to memorialize the 80th anniversary of the executive order that authorized the incarceration of people of Japanese ancestry during World War II.

The event, which took place at the Japanese American National Museum and was livestreamed to the public, featured activists and scholars working on issues regarding the Japanese American concentration camps and reparatory justice.

Executive Order 9066 removed approximately 120,000 people of Japanese ancestry from their homes along the Pacific coast and sent them to 10 concentration camps across the Western and Midwestern United States, according to The National WWII Museum. The order followed the Japanese bombing of Pearl Harbor and the U.S. entrance into World War II in December 1941.

Although the Office of Naval Intelligence and the FBI believed most Japanese Americans were not threats to national security, mounting hysteria and military pressure led then-President Franklin D. Roosevelt to sign the executive order in February 1942, according to the museum.

Emiko Kranz, an Asian American studies and public health graduate student, spoke at the Day of Remembrance event. Kranz, whose grandparents were incarcerated in the Granada and Gila River concentration camps, said Japanese Americans had to fight for survivable living conditions in the camps as they faced inadequate medical care, food and education for their children.

She said in addition to separating families and removing them from their homes during the war, the U.S. government also fractured the Japanese American community through its loyalty questionnaire.

In 1943, the War Relocation Authority and the War Department administered a questionnaire that initially asked incarcerated Japanese Americans if they would be willing to serve in the U.S. Army and renounce their loyalty to Japan, Kranz said. The community became divided on where its allegiances should stand, especially when those who were deemed disloyal were placed in the Tule Lake concentration camp, Kranz added.

“This questionnaire deepened divides within the Japanese American community, as a false dichotomy of loyal and disloyal Japanese Americans arose within the camps themselves,” Kranz said. “Answering to the country that imprisoned you and those you love was anything but simple.”

Renee Tajima-Peña, an Asian American studies professor, said her uncle was incarcerated and relocated to Tule Lake in California. She added that, while at Tule Lake, her uncle would write letters to his family, and he was later transferred to the Heart Mountain camp in Wyoming.

“He would write letters, and my grandmother was so distraught, she would burn all the letters,” Tajima-Peña said.

Japanese Americans had to rebuild their lives following the closure of the concentration camps, Kranz said. She added that because Japanese Americans were only permitted to take what they could carry to the camps, many were forced to sell their possessions and had little to return to after the war.

Japanese Americans’ economic losses from World War II may total between $1 billion and $3 billion, according to Densho, a nonprofit organization dedicated to preserving the histories of incarcerated Japanese Americans.

Starting in the 1960s, Japanese Americans began the fight for reparations to hold the government accountable for the harm it inflicted on the community, Kranz said. Notably, she said the 1980 Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians provided Japanese Americans the opportunity to publicly share their incarceration experiences, adding that more than 500 Japanese Americans eventually testified. These testimonies ultimately led to the Civil Liberties Act of 1988, which provided a presidential apology and $20,000 to every surviving Japanese American incarcerated during the war, Kranz said.

Some Japanese Americans initially resisted speaking about their traumatic wartime experiences, said Kathy Masaoka, the co-chair of Nikkei for Civil Rights and Redress and a panelist at the Day of Remembrance. However, survivors’ testimonies play a critical role in informing younger generations, Masaoka said.

“It was such an eye-opener and education, and we just couldn’t stop listening,” Masaoka said. “It galvanized and sustained the movement for reparations.”

Japanese Americans’ reparation success was made possible in part by the support and example of the Black community, Masaoka said. According to Visual Communications, a nonprofit organization dedicated to Asian Pacific American film and media, prominent Black leaders such as former LA Mayor Thomas Bradley spoke in support of reparations at the 1981 hearings.

Masaoka added that the Japanese American community must now do its part in supporting the reparations movement for Black Americans.

Dreisen Heath, a researcher and advocate for Human Rights Watch and a panelist at the Day of Remembrance, said reparations are critical in allowing communities to heal from the trauma of the past. She added that House Resolution 40, which proposes the establishment of a commission to study and recommend reparations for Black Americans, is critical in enabling Black individuals to share their experiences of injustice as Japanese Americans did more than 40 years ago.

[Related: Activist groups petition Congress to enact bill examining effects of slavery]

“If we do not patch this up to move forward, we can’t have these goals of reconciliation and equality,” Heath said. “You cannot do that without reparations.”

Interracial solidarity is critical for the passage of H.R. 40 and redress for Black Americans, who have yet to receive a national apology for their past enslavement and reparations for forced labor, racial massacres and other acts of brutality, Heath said.

Tajima-Peña also said Japanese Americans have a moral obligation to defend the rights of other minority communities. In addition to supporting the Black community, Japanese Americans have also advocated against the racial profiling of Muslim and Arab Americans following 9/11 and have spoken out against the separation of immigrant families at the border, Tajima-Peña added.

Thus, the Day of Remembrance is not about nostalgia or remaining in the past but is instead a way for Japanese Americans to stand with other communities, Tajima-Peña said.

“It’s about that solidarity,” Tajima-Peña said. “It’s keeping that memory alive through action.”