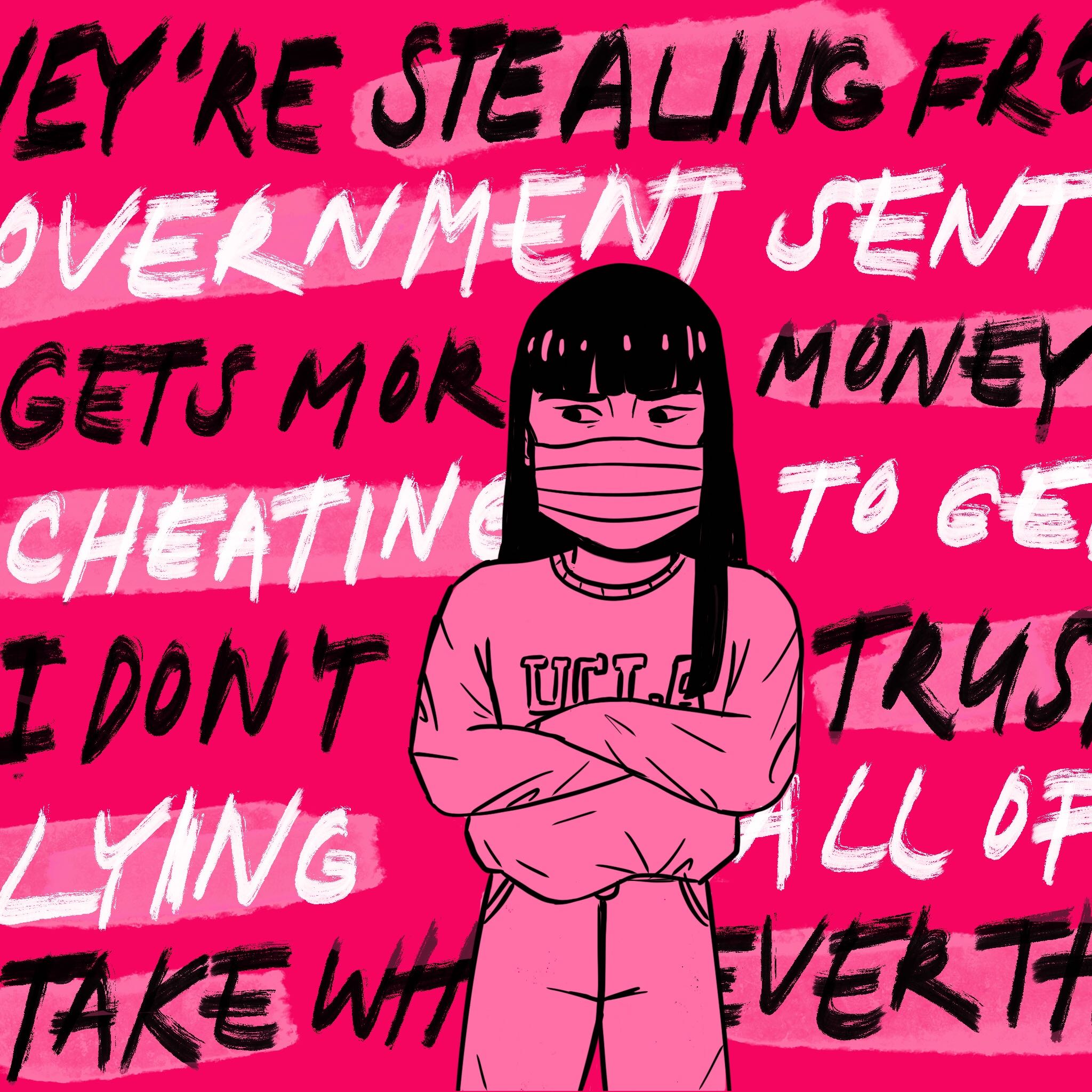

Academic espionage accusations unfairly target Chinese international students

(Courtney Fourtier/Daily Bruin)

By Lena Nguyen

Feb. 10, 2020 12:43 a.m.

They say it’s better the devil you know than the devil you don’t.

But categorizing Chinese international students as the enemy shows that universities throughout America fail to understand either.

Xenophobia against Asian and Asian American communities on college campuses has skyrocketed since the coronavirus outbreak. But these are not new acts of aggression against Chinese students – rather, this is only the latest in a larger pattern of a modern Red Scare.

Last July, Yi-Chi Shih, an adjunct professor of electrical engineering at UCLA, was convicted of illegally scheming to obtain military-grade semiconductor chips from a U.S. company. In the plot to send the technology to a Chinese company for replication, Shih’s actions added fuel to the existing fear surrounding academic and intellectual property espionage.

In 2018, President Trump threatened to ban all Chinese international students from studying in the United States. The FBI encouraged universities to monitor those who may be involved with Chinese entities, leaving academics nervous to collaborate with Chinese scholars on research projects. And hundreds of students are left with visa delays or denials to return to America to complete their studies.

Between the 2018-2019 school year, UCLA had 11,942 international students. Chinese students made up 48.9%.

That’s a number the university can’t afford to lose if antagonistic policymaking puts international admissions on the line.

Preserving the integrity of academic research is vital, but allowing xenophobic paranoia to run rampant only harms the diversity of a UC education. Chinese international students and academics are attracted to the American higher education system, but hostility and suspicion are deterring intellectual collaboration. National security interests are not mutually exclusive with a culturally diverse campus, and administrators need to be defending their campuses in the midst of academic decisions being made by career politicians.

The microscope has targeted Chinese academics long before this.

Over the past two years, prominent politicians have called for the shutdown of Confucius Institutes, and U.S. and Chinese cultural and language exchange partnerships, with concerns about Chinese spies. There are currently 500 Confucius Institutes internationally and five in California – including one at UCLA.

Since its founding in 2006, funding from the Chinese government’s ministry of education has launched nationwide Confucius Institutes into a position of high scrutiny.

And such concerns are not lost on UCLA administrators.

David Schaberg, dean of humanities and a member on the board of directors of the Confucius Institute, said he recognizes how Chinese funding in American academia is perceived.

“Especially for faculty, (Confucius Institutes) sometimes have done great good – but because of the way they’re set up and because of sometimes not being very transparently integrated into what’s going on (on) campus, that can create a lot of suspicion,” Schaberg said. “I think the overall (political) climate makes it relatively easy for people to attack the Confucius institutes and to question what they’re doing on campuses.”

Yet the reality is hardly sinister.

Hanban, the Chinese government office responsible for funding the Confucius Institutes, allows UCLA to invest in cultural projects that resources here wouldn’t otherwise allow. Between 2008 and 2017, UCLA has been gifted $2,774,486 from Hanban for Confucius Institute operations and study abroad subsidies for students. The funding also pays classroom teaching assistants for local K-12 schools, allowing international graduate students to participate in Mandarin teaching programs and English training.

Meanwhile, David Geffen’s donations to UCLA put his name on a couple more buildings.

The Confucius Institute is quite clearly not the international spy hub it’s made out to be. And because Hanban offers the funding before it’s allocated toward individual projects or approval of scholarships, the Chinese government isn’t dictating how that money is spent – UCLA is.

And they seem to be using it for a whole lot of good.

But if political rhetoric has anything to do with it, this relationship is at stake. Political animosity between the United States and China in the past few years has created more than just an awkward working relationship between the Confucius Institute and American universities – it’s shifted the culture of inclusivity on campus.

UCLA spokesperson Ricardo Vazquez, in an emailed statement, said that the growing accusations over academic espionage will not affect admissions.

“In terms of admissions of Chinese international students, there are no changes,” Vazquez said. “UCLA will continue to look for students who can contribute to and benefit from a UCLA education.”

However, international students are feeling anything but welcome.

Leo Liu, a second-year computer science student, said that Chinese international students are the victims of larger political tensions between the two nations.

“It’s impossible for undergraduate students here to be accused of academic espionage. What is there for me to spy on?” Liu said. “If the general atmosphere in America is something like this, I would say that less and less people will choose to go study in America.”

Intellectual property espionage from foreign actors does pose a great concern to the United States, and some would argue that it’s better to be safe than sorry when it comes to invaluable research findings. A 2017 report from the Commission on the Theft of American Intellectual Property concluded that intellectual theft from China has cost American businesses between $225 billion and $600 billion annually. Certainly, even UCLA has experienced a run-in with IP theft.

But this doesn’t justify categorizing Chinese students and world-renowned academics as potential conspirators, especially when these crimes rarely occur on campus. Cyberattacks are typically committed by tech firms and businesses aiming to steal trade secrets, while those simply looking to further their education are left paying the price for an academic arms race.

The accomplishments of American universities are not just their own – a diverse student and faculty body is essential to academic progress.

And if that changes, the significance of excluding those groups will become overwhelmingly clear.