UCLA professors abroad search for “˜God’ particle to answer life questions

UCLA professors have been actively involved with experiments within CERN laboratories on the Swiss-French border.

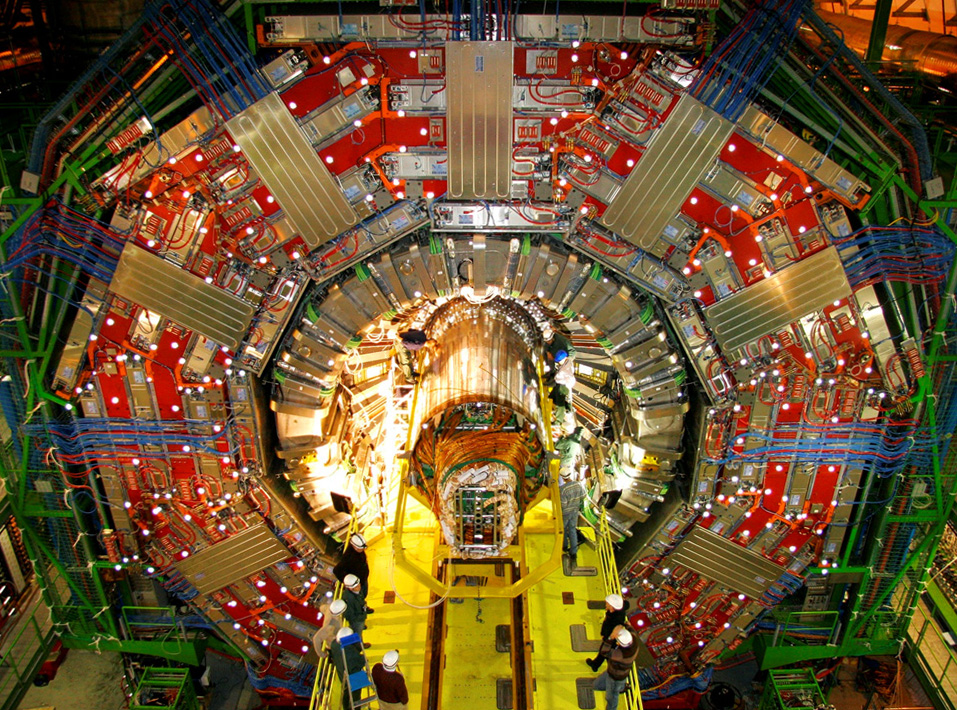

Courtesy of Michael Hoch

By Elizabeth Case

Sept. 16, 2011 4:16 p.m.

Case

Editor’s note: For the next six months, Bruin reporter Elizabeth Case will be living in Germany’s capital city of Berlin, reporting on life abroad while taking classes at Humboldt Universität. This biweekly column is a collection of insights, tips and advice from a student traveler.

As we stepped off the tram 100 meters away from the Swiss-French border, a huge, bronze globe dominated the skyline. The sign in front read “CERN: Accelerating Science.”

We had arrived at the largest particle physics laboratory in the world.

Rachel Woods-Robinson, a third-year UCLA student, and I had spent the previous two weeks hiking around the highest peak in the Alps.

We started and ended our tour of Mont Blanc in Geneva, Switzerland, and, as two physics students, spent our last day at one of man’s most advanced scientific facilities.

We were particularly interested in learning more about the laboratory’s Large Hadron Collider, which has received press in the past for its search for the “God” particle ““ the Higgs boson ““ and its supposed ability to create Earth-eating black holes.

Fear not, UCLA professor of physics Robert Cousins assured us, there is absolutely no chance the LHC is going to destroy the world.

Cousins has worked at CERN ““ also known as the European Organization for Nuclear Research ““ for almost 20 years, and now splits his time between researching in Geneva and teaching in Los Angeles. He acted as our real-life-scientist guide around the Compact Muon Solenoid project, one of CERN’s six main experiments.

The history of the Compact Muon Solenoid, a machine that collects information about proton collisions, is closely intertwined with UCLA. Cofounded by David Cline, a UCLA professor of physics, the project’s first meeting was held on campus in 1994. The machine was partially constructed at a laboratory across the street from the Weyburn Terrace apartments.

Cline and his group began building the machine in 1998. It was installed in CERN in 2008 and recorded its first pieces of data in March 2010.

UCLA has two main groups involved in the solenoid project: Cline works and maintains the actual machine, while Cousins focuses on information analysis.

“This year and next year, we hope that the data will reveal new physics,” Cousins said.

Either integral questions about the laws of nature will be confirmed, or they will need to be completely revamped. Scientists are looking for the Higgs boson, a theoretical particle vital for the Standard Model theory in quantum physics.

To find the Higgs boson, scientists accelerate protons to near the speed of light in the LHC, then smash those protons together to release the protons’ building blocks.

“Protons are like a bag containing quarks and gluons,” Cousins said. “We (make them collide) and then run relativity backwards to find out what was there. … Things would have to go badly to not have found it by 2012.”

David Saltzberg, a UCLA professor of physics responsible for building the final pieces of the Compact Muon Solenoid, said the collider is like a giant, extraordinarily powerful microscope.

“It has so much pure discovery potential,” Saltzberg said. “Who wouldn’t want to look at the universe this way?”

With Europe in economic turmoil, there has been some skepticism over whether such research is worthy of the laboratory’s $800 million budget.

Yet, Saltzberg said research at CERN often results in fruitful technological “spin-offs.”

These spin-offs include the World Wide Web, which was invented at CERN in 1989 to aid international scientific collaboration. Cline was a member of the original experiment that led to the Web.

The technological advancements, however, are secondary to the science, Cline said.

“I do (this research) because I’m very interested in the nature of the world,” he said. “Cavemen had drawings of the moon. This curiosity goes back to the very origin of humanity.”

At the end of next year, whether or not scientists discover anything new, the hadron collider will be shut down for two years for retrofitting. When it reopens in 2014, the improvements will allow protons to collide at even greater energies.

“This is the greatest physics experiment of this generation,” Saltzberg said.

Email Case at [email protected] and follow her on Twitter, @elizabeth_case.