Students bear dreams on burdened backs, addressing systemic school inequity

By Tia Jolie Cooper

June 29, 2025 6:49 p.m.

This post was updated July 7 at 7:57 a.m.

In the American education system, a student’s zip code can shape everything – from textbook quality to future expectations.

Students from underfunded schools who reach elite universities carry the burden of systemic neglect.

Equity in education isn’t just about recognizing unequal starting points; it requires action.

This means we must invest in underfunded schools, expand support and enact policies that uplift students facing poverty and systemic barriers.

Recognition is only the first step – change must follow.

I grew up in Vallejo, California, a city rich in culture yet marked by economic instability. I was lucky to have a strong support system at home, but many of my classmates weren’t so fortunate.

Academic success often came second to survival.

This story isn’t unique. Across the country, students in cities similar to mine navigate economic instability both at home and in classrooms stretched thin by a lack of resources.

Does this outcome ensue as a result of schools striving to do their best under such constraints? Is it due to the historic exclusion of communities from funding? Is it the cause of the entire system?

Sarah Bang, a professor at the UCLA School of Education and Information Studies and the director of Public School Partnerships, reframes these questions.

“One point I hear folks say, ‘The system is broken.’ I would respectfully disagree,” Bang said. “The system is doing exactly what it was designed to do.”

Bang emphasized that underfunded schools reflect a larger, interconnected system that is overburdened and under-resourced.

Kimberly Agredano, an education and social transformation student, recalled teachers holding low expectations for her future.

“A lot of my teachers always said I wasn’t going to be anything. I’m not going to have a successful career.”

This type of environment lacks resources and leads to a decline in confidence. Agredano’s path to college wasn’t built on guidance, but rather on persistence and the need to carve out her own future.

Marisol Mercado, a second-year education and social transformation student, said limited resources affected both her preparedness and her confidence.

“My high school didn’t offer a lot of AP classes,” she said. “Instead, they signed us up for dual enrollment.”

Despite earning college credits, Mercado’s first UCLA English class was overwhelming.

“I cried every time there was an assignment due,” she said. “I don’t know how to analyze literature. I don’t know how to write a proper essay.”

High school praise hadn’t prepared her for college rigor, Mercado said. She added that she worked 40-hour weeks during the summer in order to put aside $10,000 for tuition. Her parents earned too much for FAFSA aid, but couldn’t afford to assist her financially with college, Mercado said.

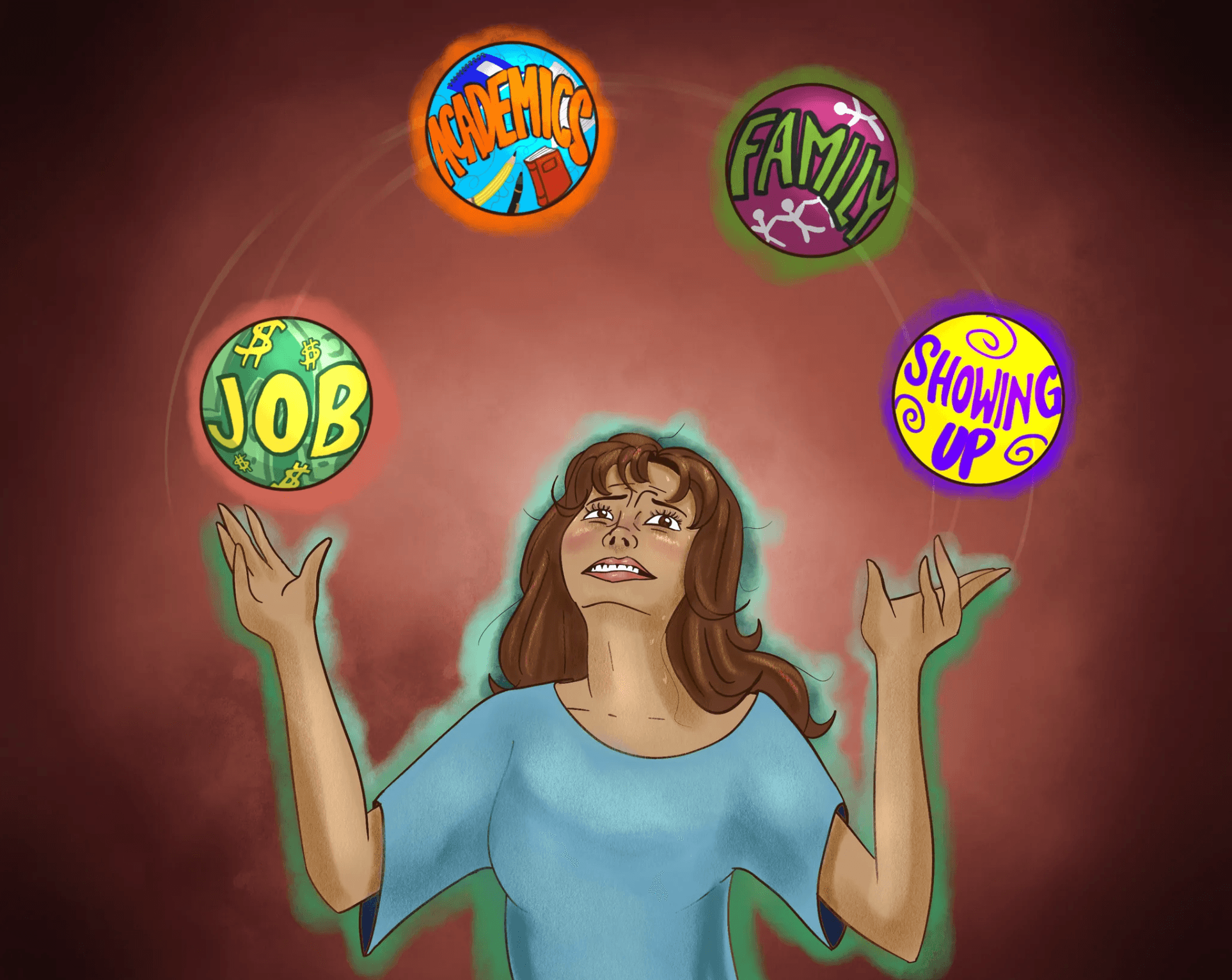

For her, college involved more than just academics – it meant jumping through hoop after hoop to stay afloat.

This neglect extends beyond academics. Dr. Julissa Muñiz, an assistant professor at the UCLA School of Education and Information Studies and a first-generation college graduate herself, said safety and survival often override learning.

Students from low-income areas tend to worry about which streets are safe or what clothes won’t put them at risk. When safety is uncertain, school isn’t the priority, Muñiz said.

Nicole Kayum, a former Vallejo High School teacher, said she witnessed the toll of structural inequality in and beyond the classroom.

“It’s already a set race, and like those cartoons of the show about equity – you’re already four laps in the back,” Kayum said.

Kayum added that she saw how trauma and instability shaped students’ lives and their relationships to learning. Constant lockdowns, grief and neighborhood violence weren’t abstract backdrops. They were part of the school routine, she said.

“There hasn’t been a lockdown all year,” Kayum said. “You don’t know how good you have it. You don’t know what these kids in Vallejo go through. They’re a lot tougher than you think, and a lot stronger.”

Reaching elite colleges brings new challenges. Academic gaps are real, but so is the disorientation of being among peers who’ve always felt as if they belonged. The pressure to adapt isn’t about ability – it’s about access.

Dawn Kurtz, the CEO of the Los Angeles Education Partnership, a nonprofit organization that partners with schools and communities to promote educational equity and improve outcomes for historically underserved students, said that academic success is only part of the battle.

“You’re comparing apples and oranges,” she said, referring to the discrepancies in what students had access to and the opportunities they could realistically pursue.

Many students also lack access to counselors, mental health care and exposure to college pathways that their peers may take for granted, Kurtz said.

Muñiz added that students from underfunded schools must quickly learn unspoken norms, including how to read a syllabus, attend office hours and talk to professors.

Bang said well-resourced students commonly arrive already fluent in these expectations. Universities, meanwhile, often overlook this disparity, treating students as data points instead of individuals.

At Vallejo High School, along with many other schools, support is there yet fragmented. Schools, districts and communities try – but the pressures of survival, burnout and instability stretch them thin.

When students finally arrive at places such as UCLA, they don’t just carry academic dreams. They carry the weight of everything that got them there.

To students battling imposter syndrome: You belong here.

You are not defined by your circumstances, but shaped by them. It is your resilience that has brought you this far.

To professors: Remember, your students aren’t cookie-cutter. What feels instinctive to some may be new to others. Make room for “basic” questions – small moments of clarity can mean everything.

True equity in education doesn’t begin with equal treatment. It begins by meeting students where they are – and walking with them from there.