‘One timeline after the other was not met’ – UCLA’s $213 million project is failing

The Ascend project involves a transformation of UCLA’s outdated financial system, a mainframe system designed in the 1980s. After seven years, the project is still incomplete, and UCLA continues to rely on the legacy system. (Liam McGlynn/Daily Bruin senior staff)

This post was updated May 22 at 9:48 p.m.

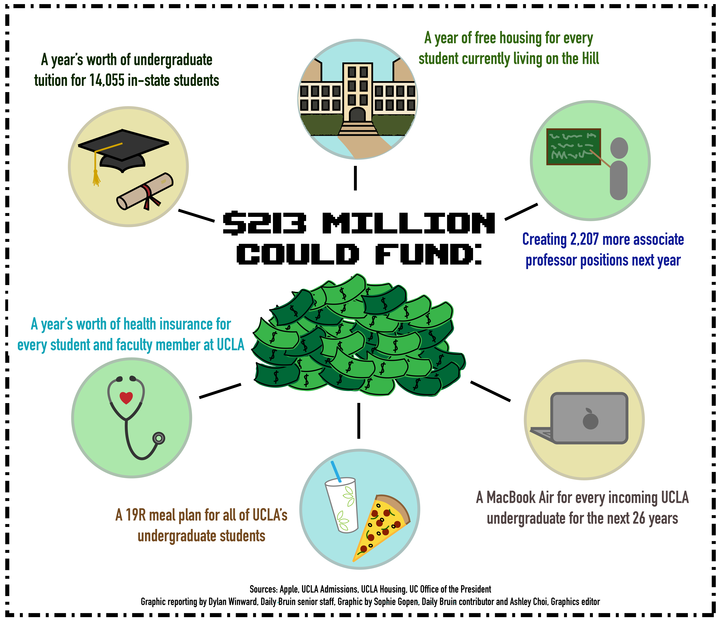

UCLA has spent at least $213 million on the Ascend Finance Transformation project, and yet, seven years after the project’s launch, it has few concrete accomplishments.

“I can’t say that I’ve actually seen a live screen for Ascend,” said Reem Hanna-Harwell, a former member of the project’s steering committee.

The initial reported budget for the project was $120 million, but, according to a presentation given during the May 2024 Ascend 2.0 quarterly town hall, the estimated total cost was projected to be roughly $286 million.

The university declined to answer exactly how much money has been spent on the project since its official start date in April 2018.

The Ascend project involves a transformation of UCLA’s financial system – moving from the current mainframe system to Oracle Cloud, modernizing the chart of accounts and upgrading all business applications which contribute data to the central finance, research and budget systems, according to the 2021 project charter. The project, directed by Digital and Technology Solutions, formerly known as IT Services, intended to replace UCLA’s outdated legacy financial systems software, designed in the 1980s when the university’s operating budget was just 7% of its current size.

UCLA has failed to provide documents relating to the project requested by the Daily Bruin over 180 days ago, despite last estimating that they would be made available Feb. 28. The law mandates that public records should be turned over “within a reasonable period of time,” according to guidance from the California Attorney General’s Office.

Reggie Kumar, UCLA’s associate director of media relations, also delayed responding to questions about the project sent March 25 for a month. He ultimately provided only a three-sentence statement.

Initially scheduled to be complete in July 2020, the project was put on hold in December 2019 and underwent various replanning phases for three years before the launch of Ascend 2.0 in October 2022.

In June 2024, the Ascend 2.0 executive sponsors – including Vice Chancellors Stephen Agostini, Michael Beck and Roger Wakimoto – announced the project’s second pause to reevaluate the implementation of Bruin Finance, the central application of the project, which was supposed to begin Aug. 2, 2024 and last up to 12 weeks. Since the pause took effect, more than 40 weeks have passed without any update.

The project remains on hold to allow for reevaluation of the scope and future plans, according to the statement provided by UCLA Media Relations.

Aine Ekoh, a product designer for Ascend, said she has received little communication about the pause or what it will mean for people working on the project. She added that she believes it is possible the project will be canceled entirely, despite the university having already spent over $200 million on it.

“I would say ‘on pause’ is just a state where they just don’t know yet, and they might be looking into things to see if it’s worth it to continue,” Ekoh said.

Two of the project’s executive sponsors – Lucy Avetisyan, the university’s chief information officer and associate vice chancellor, and Agostini, the vice chancellor and chief financial officer – refused an interview and would not specify exactly what the project has accomplished thus far.

But, according to the DTS website, the only accomplishment seems to be the modernized application BruinBuy Plus. UCLA has not transitioned from the mainframe financial system to Oracle Cloud or fully implemented the UC-wide Common Chart of Accounts, a process the University of California Office of the President mandated to be complete by July 2023.

A chart of accounts is a comprehensive directory for managing financial accounts and transactions, according to a Microsoft Learn article. Bill McCarroll, UC San Diego’s former financial accounting director, said it would theoretically be possible to map the legacy Chart of Accounts to the new Common Chart of Accounts without upgrading the financial system, but it is not a good strategy.

“It’s really clumsy, and it’s not going to be totally in line with what UC would expect in the common chart data,” he said.

McCarroll added that it would probably require just as much work as creating a new financial system.

“Our financial system is currently a mainframe system,” said Hanna-Harwell, the senior associate dean of finance and administration of UCLA’s Humanities division. “This is an ancient relic of a system, really. And there’s probably very few people left on campus that know how to maintain this system.”

Eliud Escobedo Jr., UCSD’s business process innovation officer, added that mainframe systems cannot support the data management needs of leading research universities, leading many UC campuses to switch.

The majority of the other UCs have successfully modernized their financial systems and transitioned to the mandated Common Chart of Accounts. UCSD, for example, launched its upgraded financial system in July 2020, despite starting the project a year after UCLA and spending only $16 million compared to UCLA’s projected $286 million.

Jens Palsberg, a member of the Ascend Steering Committee from 2019-2022, said the project was too big, with too many competing voices failing to converge on a workable plan of action. Representatives initially appointed from the College of Letters and Science and the David Geffen School of Medicine have since left the committee.

“That’s something about UCLA that makes convergence difficult,” Palsberg said. “I could see how one timeline after the other was not met.”

UCSD, however, was able to bridge the gap between the competing interests of the administration and academic faculty and successfully got both the medical center and the foundation on board, said Kevin Chou, the deputy chief information officer at UCSD.

The key was fostering collaboration and addressing individual concerns, he added. He said his team facilitated dialogue between the central administration and academic unit leaders, gathered feedback from both subject matter experts and those using the software, and provided comprehensive training to prepare everyone for the new system.

Palsberg said the early stages of UCLA’s project felt collaborative, but by the time Avetisyan was appointed CIO, the supportive tone had faded entirely.

Internally, UCLA has also struggled to decide how to best manage the project, alternating between relying primarily on consultants and pushing for more in-house work. Because of early issues with the Huron consultants, for example, IT leadership moved project leadership in-house, Palsberg said. The Business Transformation Office was tasked with project management.

“By terminating consultant partner contract, UCLA will lead the project and primarily staff with in-house resources and supplemental expert resources,” said Omar Noorzai, the executive director of that office, in a written statement to the UC Board of Regents.

But the BTO was later relegated to IT Services in January 2021, and Avetisyan initiated a shift back to consultancy work, according to a complaint filed by Noorzai. He sued both the university and Deloitte – which was consulting on the project – and alleged the university violated competitive bidding laws and fired him in contravention of whistleblower protection laws.

Noorzai’s case will go to a jury trial in November. The Daily Bruin was unable to verify his allegations.

UCSD, on the other hand, did almost all the work in-house. McCarroll said the team considered opting for consultants but found it to be an unaffordable option. Since the launch of Ascend 2.0 in September 2022, UCLA has spent at least $92 million on consulting work.

Not only did the in-house option allow UCSD to save money, but McCarroll said it also allowed it to avoid design conflicts between consultants and staff.

“You don’t want consultants to design a system when they really don’t understand how you want the system to work, right?” McCarroll added.

UCSD had to deal with the disadvantage of diverting operational resources to the project, McCarroll said, but, by doing the work in-house, its staff gained a comprehensive understanding of the system that allowed them to tackle the bugs and problems much more efficiently after the project went live.

Without consultants, McCarroll said UCSD relied on Oracle to answer questions and provide advice. However, UCLA has had minimal contact with Oracle, Ekoh said.

Ekoh added that, despite having direct contact with vendors at other companies she has worked at and having found that contact helpful, her team did not have any access to an Oracle representative.

“There was a lot of working around Oracle,” Ekoh said.

Miscommunication between Oracle and the university continues to exist as project leaders question whether to continue with Oracle as the primary software provider or explore alternatives.

“Oracle’s lack of responsiveness – particularly regarding licensing costs and support – has emerged as a concern. This issue is part of the ongoing evaluation,” said Jennifer Ferry, UCLA’s associate chief information officer and Ascend 2.0 project manager, in a March 2025 written statement to the UC Board of Regents.

Palsberg spoke at length with UCSD leadership to understand why they succeeded where UCLA did not, but said he could not explain exactly what he discovered without upsetting half a dozen vice chancellors at UCLA.

He added that the Ascend team did not complete a single modernization during his time on the committee.

Graphic reporting and interactive by Liam McGlynn, Daily Bruin senior staff.

The first modernization did not come until January 2024 – after he had left – when BruinBuy Plus, software that manages purchasing and vendor payments, went live. David Schaberg, the former dean of humanities at UCLA, said the software implementation did not go well, with staff complaining that the system was inconvenient to use.

“There’s been a lot of complaining on campus about the very miserable turnaround time in reimbursements for vendors with whom UCLA does business,” he said.

In the first four months of the software’s use, a backlog of over 50,000 unpaid invoices accumulated, causing monthslong delays in payments. In response, project leaders assembled a “Tiger Team” in April 2024 to stabilize BruinBuy Plus, successfully reducing the backlog – though not without consequences.

These delayed payments and high outstanding balances caused some vendors to refuse future purchase orders made by the university. Other businesses, however, continue to accept them, despite persistent challenges in receiving payment.

Ramin Messian, the owner of Enzo’s Pizzeria, said that around 30% of the purchase orders UCLA sends to his business are incorrect or never paid. Meanwhile, the university owed Lamonica’s NY Pizza nearly $25,000 last year, according to an assistant general manager.

Beth, a UCLA administrative assistant who requested partial anonymity because of fear of retaliation, complained of an absence of communication between DTS and BruinBuy Plus users when making updates to the system.

“They make changes. We’re not notified, and then we have to scramble and figure out what has happened,” she said. “The lack of updating those of us doing the work is rude, not thoughtful, not helpful, creates extra work.”

Today, over a year since its implementation, BruinBuy Plus still poses issues, some of which require direct assistance from IT or Accounts Payable. Beth noted, however, that she has had difficulty reaching IT representatives and has found them mostly unable to answer questions, frequently finding it easier to cancel purchase orders altogether and starting over.

Palsberg said the finance department at UCLA is understaffed, and positions are difficult to fill, in part, because the financial system is troublesome.

“I kind of feel the pain of the people who work with the finances at UCLA,” he said. “The work could be more smooth if we had a better financial computer system for them to work with.”

Since BruinBuy Plus’s implementation, Beth said experienced staff members have left the department, seemingly to avoid having to deal with the confusion caused by the system’s issues.

“In finance, multiple people have left in highly visible positions and taken other positions on campus – not necessarily even at the same pay grade – just to get away from all the headaches with the transition process,” Beth said.

Schaberg said the university also struggled with the switch to using UCPath to process its payroll.

“That was widely felt to be an expensive kind of disaster,” he said.

Palsberg said the implementation also created a significant backlog. Staff struggled to find a solution, and the new system brought many mistakes, he added. Palsberg said he had a mistake in his own paycheck, as did former CFO Gregg Goldman.

Project management has been a longstanding weak point for UCLA DTS. Mark Bower, a former director, said IT Services did not have a strong project management office prior to 2020 and did not have standardized procedures for how to approach or manage a project.

Bill Jepson, former chief information and technology officer for the School of the Arts and Architecture, said the team in charge of UCPath’s implementation in 2018 underestimated the challenges they faced. They experienced many delays, and both the time and financial costs were ultimately greater than the savings, he added.

IT leadership also did not do a good job of listening to the needs of the academic administrative units throughout the centralization process, Jepson said.

“They were looking at their own problems and solving those, but they weren’t good at trying to understand what our problems were,” he said. “They didn’t even care to figure out what our needs were.”

The Ascend project is just one of many key initiatives part of a larger IT transformation effort and not the only one that has experienced pushback. Other initiatives include a security transformation, classroom technology modernization, improved data governance and internal reorganization.

The internal reorganization initiative, Reimagine IT: Talent, involved the creation of hundreds of new job descriptions and titles and required all nonunion employees of central IT services to reapply for new positions.

Max Belasco, the UCLA co-chair of the University Professional and Technical Employees-Communications Workers of America 9119 – which has gone on strike four times this year and alleged unfair labor practices – said many employees who had been with the university for a number of years did not get the jobs they applied for, many of which were equivalent to their former role.

“People who I know that have been really dedicated to the mission of higher education – and some people have done it for quite a period of time – did not feel like they were being acknowledged or considered part of this ‘True Bruin’ community that we like to imagine,” said Belasco, the manager of Bruin Learn and clinical IT at the UCLA School of Law.

Carlos Inductivo, a systems administrator, said leadership did not communicate with the staff ahead of or throughout the reorganization. He said the reapplication requirement was announced unexpectedly at an all-staff meeting in August 2023.

“People were freaking out when they saw it,” he said. “It was pretty shocking.”

Inductivo, who is union represented, did not have to reapply for his position. However, he was notified that he would be transferred from BruinCast to a role he did not understand in the Housing and Hospitality unit, an entirely different organization, in December 2024. He said he had no idea what the role would entail or whether he was qualified for the position, as of October.

“It’s causing a lot of anxiety not knowing what my future job will be, what my hours will be like,” he said.

Additionally, the director of BruinCast, who Inductivo said ran the department flawlessly, was not rehired. After the transition to new leadership, Inductivo said the department began receiving a lot of complaints from students and faculty, which had never been a problem during his two years in the department.

Inductivo said the university was late in getting roles filled by as much as six months in some cases. The planning phase started in 2022, but there were 84 unfilled positions as of October 2024, and the last positions were not filled until the end of 2024, Ferry said.

USC IT – where Avetisyan previously worked – underwent its own reorganization in 2019 and completed the process in roughly a year, less than half the time UCLA did, said Douglas Shook, the chief information officer at USC from 2015-2023.

The completion of the Reimagine IT: Talent initiative in April coincided with the announcement of the department’s rebranding to UCLA Digital and Technology Solutions.

The May 2024 town hall presentation outlined two options for the future of Ascend: the first being a two-year delay and the second an indefinite pause. One year later, UCLA looks poised to restart the project for the second time after completing a reassessment of the program.

“I realized that this will never, ever happen at UCLA. As in, I could not see a realistic path to make it happen,” Palsberg said.

Having already spent more than $213 million with limited visible progress, questions about the project’s long-term viability and eventual cost remain. A UCLA spokesperson said the university will provide an update on the finalized plan later this year, seven years after the official start of the project.