Beyond the Statute: Homelessness must be addressed as a public health priority

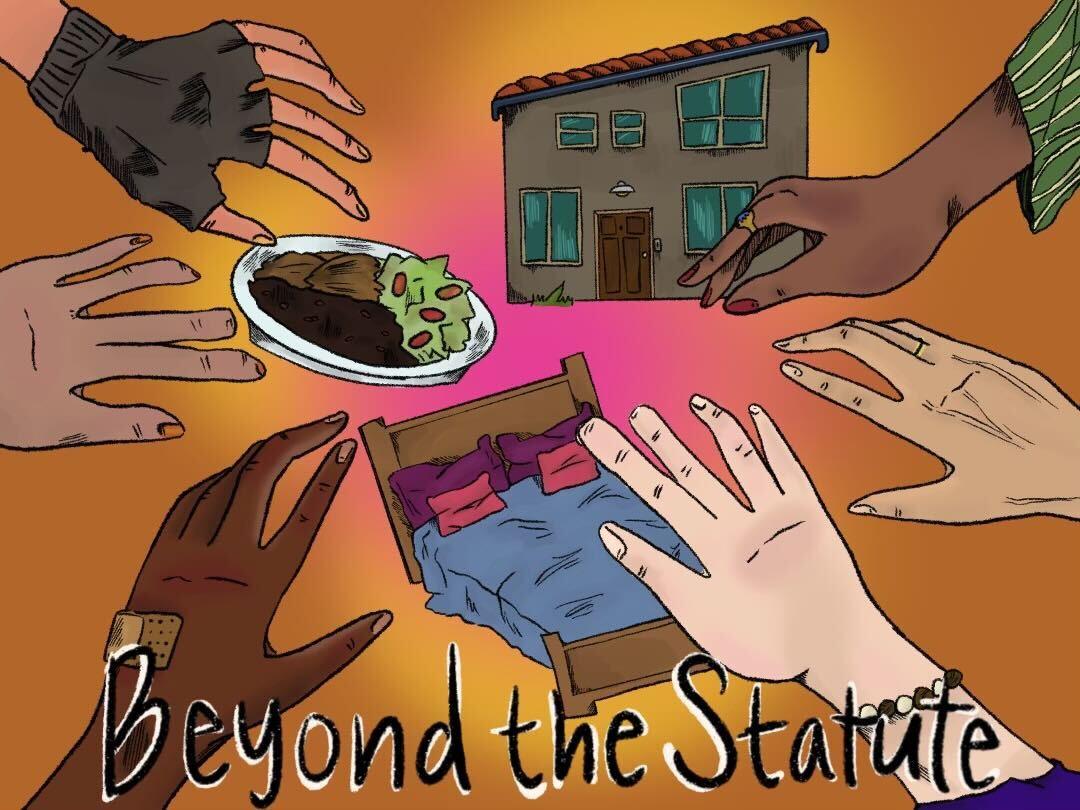

(Yuri Mansukhani/Daily Bruin)

By Sierra Benayon-Abraham

Jan. 16, 2025 12:03 p.m.

This post was updated Jan. 16 at 8:32 p.m.

“Beyond the Statute” is a series created by Sierra Benayon-Abraham, an assistant Opinion editor and third-year public health student. In these columns, she will be exploring various public health policies, laws and experiences that different marginalized communities encounter, along with the truths behind them. It is her goal to share the importance of understanding health care on a universal level while highlighting both the disparities and inequities that exist for distinct marginalized groups. With UCLA’s campus abounding in students interested in health care, law and public policy, Bruins who have either an interest in or experience with the topic are welcome to submit op-eds or letters to the editor to be published as part of this series to represent the many facets of health care policy.

A bed to sleep in at night provides warmth. Fresh food in the fridge is fuel. A roof over your head offers safety. Together, these privileges define an essential space for every human being: a home.

Housing is health care.

Health and homelessness are inextricably intertwined. Living without stable housing exacerbates health issues, while chronic illnesses can prolong homelessness.

“It’s hard to be healthy without a home,” said Ippolytos Kalofonos, a psychiatrist, anthropologist and assistant professor-in-residence at the UCLA David Geffen School of Medicine Center for Social Medicine.

On a single night in January 2023, 653,104 people in the United States experienced homelessness – a record high according to the National Alliance to End Homelessness.

The U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development reports that individuals in homeless shelters are more than twice as likely to have disabilities compared to the general population.

According to the National Coalition for the Homeless, 36 people experiencing homelessness die each day.

It is evident that current health care policies are under-serving those experiencing homelessness.

“Healthcare laws and practices are far from adequate or equitable for unhoused populations,” said Troy Vaughn, CEO and President of Los Angeles Mission, an organization that provides comprehensive programs to address the needs of people experiencing homelessness, in an emailed statement.

A lack of health insurance or funds to pay for medical treatments leaves many homeless individuals relying on emergency rooms for care. Yet, this often guarantees extreme costs compared to receiving treatment from a primary care physician.

Chronic illnesses such as diabetes, heart disease, HIV and AIDS can occur at three to six times higher rates among homeless populations, according to the National Coalition for the Homelessness. Moreover, mental health challenges and substance abuse disproportionately affect these individuals.

“Accessing healthcare while experiencing homelessness is fraught with challenges,” Vaughn said in the emailed statement. “Many of our neighbors face systemic barriers such as lack of documentation, transportation issues, and minimal knowledge about their healthcare rights.”

A lack of a safe place to store medications can complicate treatment for chronic conditions such as diabetes, asthma and high blood pressure.

Accessing a healthy diet can be difficult when your meals primarily come from shelters and soup kitchens, which are often serving donated food items high in sugar and starches.

Even minor injuries, such as cuts and scrapes, can lead to debilitating infections if a patient lacks the opportunity to change used bandages out for clean ones, a common occurrence among homeless populations.

“Many of our neighbors report being treated with bias or outright refusal of care because of their appearance, lack of hygiene, or inability to pay,” said Vaughn in the emailed statement.

According to a 2010 national study, 73% of respondents experiencing homelessness confirmed having a minimum of one unmet health concern. These medical challenges include an inability to receive medical or surgical treatment, prescription medication, mental health care, optometry care or dental care.

How can these health issues be resolved without addressing the structural failures that perpetuate them?

“We have the means to house people,” Kalofonos said. “We don’t have the will.”

Recovery is often associated with hospital beds and intense medical care, but we may be overlooking the most critical component of health care: housing.

Neglecting the importance of housing in maintaining public health can fuel vicious cycles of poverty. These cycles may begin with the loss of employment due to an extended illness. However, without a stable source of income to support the cost of health care needs, a person may not be able to properly heal to the point where working can resume.

In order to break this cycle, we must begin by viewing the health inequities and stigma surrounding those experiencing homelessness as a public health crisis and priority.

The Midnight Mission, an organization that was founded in 1914, works with homeless individuals and families in order to help those in need regain self-sufficiency and independence – both crucial steps to combating homelessness.

“The Midnight Mission demonstrates how targeted support – such as meals, recovery programs, and housing assistance – can help people transform their lives,” said Heidi Struble, the communications coordinator at The Midnight Mission, in an emailed statement. “Students can be inspired to see how small acts of kindness and advocacy can lead to significant societal changes.”

Addressing homelessness as a public health priority demands comprehensive policies that work with homeless individuals to meet their long-term needs. Housing must be seen not as a privilege, but as a vital component of health care.

After all, we have now reached the point when a person’s zip code – or lack thereof – has the potential to act as a stronger determinant of health than their genetic code.