Opinion: By leaving my comfort zone studying abroad in London, I realized my sense of self

Tavian Williams (pictured) walks along cobblestone streets of Old Town, the oldest neighborhood in Edinburgh, Scotland. (Courtesy of Tavian Williams)

By Tavian Williams

July 27, 2024 9:06 p.m.

This post was updated Aug. 18 at 8:42 p.m.

“I am descending into London. Delta 186. When I land, I’m on my own. No one waits to pick me up at baggage claim.”

This journal entry, written Jan. 10, was the first of many during my two-and-a-half-month-long experience studying abroad in the United Kingdom.

I felt no fear embarking on my own. My biggest concern was navigating the Underground tube system from Heathrow to Central London with three suitcases and a duffle bag.

I only had a strong urge to escape the life I had always known.

My time spent abroad allowed me to start over again and craft an identity of my most authentic self: the version of myself that I easily imagined but didn’t know how to tap into.

I intended to undergo this process when I first entered UCLA. I expected to become vivacious, social and adventurous instead of keeping predominantly to myself.

But I quickly learned that life doesn’t always work out as planned. Being only 60 miles from home, it was too easy to fall into old habits, clinging to the safety of solitude when I knew I longed for company.

I needed to escape my comfort zone.

I figured about 5,440 miles away would be sufficient to remedy these tendencies – in a place where no one knew me, and I was free to debut whoever I wanted to be.

I arrived at my tube station: Tottenham Court Road. The wind chill made the air feel barely above freezing. It smacked me into reality when I hit the street. I looked around for any recognizable landmarks from previous visits to London, but everything was backward.

I was still thrown off by how cars drove on the left side of the road instead of the right. I passed by a green McDonald’s as I hauled my entourage of suitcases along the uneven pavement before I waved the white flag and hailed a black cab.

Despite the initial confusion and the differences, I felt a strange excitement experiencing London from a local’s perspective, making it feel as if it was my first time visiting again.

Navigating British English was my initial hurdle. “Queue” instead of “line” and “You alright, mate?” as a greeting threw me off.

But I acclimated to English living, settling in by my second day and cooking in my flat as if I’d lived there for years. I felt 30. I had an apartment and the autonomy to shape a home for myself.

Since it was partly an extension of me, I worked hard to keep it clean and guard it with care. I loved my flat and suitemates. Emotionally, I thrived abroad.

Socially, however, I remained a wallflower.

“I exhausted all my conversations with people I didn’t know, introducing myself and such, then resorted to my introverted tendencies of hovering by people I knew the most, awkwardly watching their conversation from the outside. It’s what I hate most about being in big social spaces,” I wrote Jan. 14.

It only worsened when the overthinking set in. Fidgety hands, misreading facial expressions and body language, twisting words, adding depth and complexities to simple things that are just that … simple!

I expected to transform automatically, but I was a tad socially awkward and somewhat clueless about making friends from scratch.

I refused to open myself up to others back home. I built a gilded cage around myself, rarely letting anyone get to know me. But I knew I couldn’t survive this term without embracing vulnerability.

I tuned out my thoughts and confided in two others in my program about feeling out of place, and we instantly bonded over our shared experiences of being introverted.

From then on, I shed the expectations I set for my experience abroad, placing myself in more uncomfortable social situations to allow my personality to shine through. I also stopped counting down the weeks until I had to return home.

Discomfort became the best friend I never had. Every week, I forced myself to have at least one moment where I said, “[expletive] it,” pushing me into social situations I typically avoided.

Letting go led me to experience my most memorable moments in London, such as riding the Underground to random boroughs to immerse myself in the unknown, going to dinner with a stranger I met at The Notting Hill Bookshop or dancing on stage in front of hundreds in a nightclub.

I traded my comfort zone for a front-row seat to some extraordinary experiences, such as going to my first Premier League match: Crystal Palace vs. Sheffield United.

In the stadium, a sea of chanting fans surged around me. Almost close enough to touch the football stars, the raw energy of the game crackled in the air.

Everything I knew about soccer came from “Ted Lasso,” so when Crystal Palace scored a goal, I wasn’t surprised when the man behind me with a South London accent slapped my back and embraced me as if we were old mates.

The best part of England was its dynamic range of activities. I could trade the electric atmosphere of the Crystal Palace stadium for a quieter adventure in the English countryside.

I took a day trip to Bath with a friend. As we traveled away from London, the urban sprawl gave way to rolling hills spotted with white flakes. When the train arrived in Bath, the city was covered in snow.

I geeked out as if I had never seen snow before, and for a day I was a kid again.

We scrambled to a hilltop overlooking blanketed beige Georgian buildings and the Bath Abbey, pelting each other with snowballs. I felt an overwhelming sense of freedom in our laughter and the cold air.

Over lunch, our local friend introduced us to his childhood friends and gave us a walking tour through narrow cobblestone streets and the Roman Baths.

These adventures, venturing beyond my comfort zone, weren’t just fleeting moments of fun.

They subtly reshaped my perspective on myself and how I interacted with the world around me.

I left my base in England during the weekends and explored six other countries, solo traveling in three of them.

In each of these places, I wanted to form my own impressions of the locations I would venture to and the people I would meet, so I did little research about where I would visit.

My encounters with the locals from each country were wholesome and made my appetite for exploration insatiable.

Although spending St. Patrick’s Day in Dublin, Ireland – a city-wide celebration where I spent the day pub-hopping with friends and Irish locals covered head to toe in green – was my runner-up choice, my favorite destination was Copenhagen, Denmark.

Denmark was the last place I would’ve thought to visit – and the friendliest and safest country I have ever explored.

I stood out among the Danish. Some people stared, but there was no hostility in their eyes – they did not make me feel like an “other.”

The same day I arrived, I felt comfortable enough to wander alone at night.

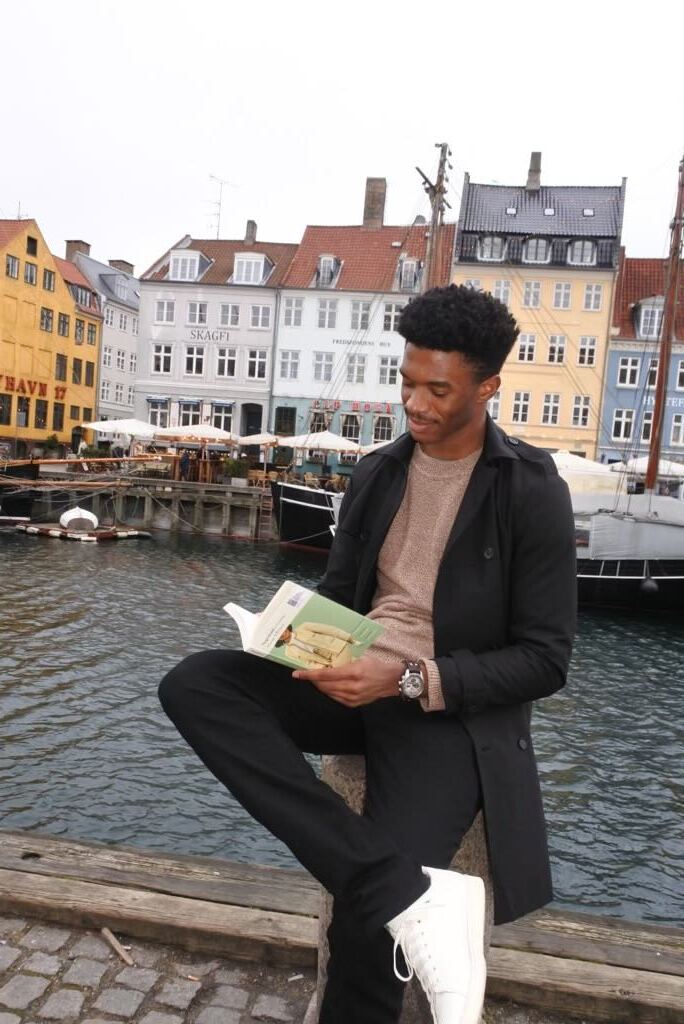

I biked freely across the city to Nyhavn, receiving welcoming gestures from locals along the way. A stranger in a cafe even invited me back to their flat to meet their puppy, but it didn’t feel unusual.

And by chance, I met someone out there.

“I met (my friends) for dinner, and their hostel mates. One was Australian, the other French. At dinner, the French girl and I sat across from one another. … I stared into her eyes until she felt the same way about me as I did her,” I wrote Feb. 6.

I was struck by her voguish fashion sense, but more importantly, her inquisitiveness and sophistication.

She was a keen photographer, and the images she captured had a visual language that spoke more volumes than words could express.

I left Denmark smitten. I never thought I would experience a rare moment too often dramatized by Hollywood in real life.

This experience led me to become an active participant in a narrative of my own, and after a month and a half of talking, I found myself on a plane to Paris for a date.

Abroad, a sense of belonging washed over me. I could freely express myself without the self-consciousness that sometimes shadowed me back in the United States. It was a stark contrast, a reminder of the work that still needs to be done back home.

Truthfully, I felt safer and more comfortable in the countries I visited than in certain parts of the States. Ironically, being from America contributed to this security.

My travels also exposed me to the harsh realities faced by immigrants and travelers perceived as “outsiders.”

On my Air France flight to Paris, immigration enforcement officers brought a man who was being deported aboard. I vividly remember one of the officers speaking kindly to me in a Scottish brogue.

But that same Scottish officer taunted the man, telling him that he was not welcome in the U.K., it was not his country and that he was being sent back to “where he belonged,” escalating an already tense situation.

The man pleaded throughout the hourlong flight, speaking English just as well as I and French at the same proficiency as a French local, but his foreign accent and immigration status othered him. Several guards surrounded him throughout the flight, even though he was tied up.

Passengers began recording the altercation, but his pleas became white noise to people’s conversations.

With my American passport, I received a level of respect and decent treatment that immigrants and travelers from developing countries were not granted.

Witnessing the disparity in treatment based solely on nationality burst the bubble of blissful ignorance that I carried as a Black American traveler in other countries, well aware of the privilege I yielded with an American nationality.

My American accent and passport gave me a warm reception in many European countries that others of the African Diaspora, whether it be Black African individuals, Afro-Caribbean or Afro-Latino, may not have had.

I felt despicable for doing nothing, especially because I knew what otherness felt like.

The encounter left me questioning if my time abroad was an illusion, giving me a false sense of security because it was so different from what I’ve always known, or if I could feel safe anywhere in the world living as I am.

During my last week in London, my parents visited. They were astonished at how much I had changed and how acquainted I was with the city. Their pride made me feel good, but I still felt like I was in a chrysalis with still so much to discover about the world and my relation to it.

But soon, my time was up.

“On the bus ride back to Bedford Place, I stared out the double-decker windshield, taking in what was once foreign, now felt like home. I thought about all my experiences and the faces I came across, and let the tears roll down my face,” I wrote March 24, my last night in London.

On the flight home, my mind felt empty, drained by all the emotions. I scrolled through my photos, hoping to feel something during that 11-hour flight.

I thought about how anxious I felt when I hosted wine and cheese nights, afraid people wouldn’t attend. But they always came.

I laughed about celebrating my roommate’s 21st birthday at Harrods and my late nights clubbing in London and Edinburgh with friends until 5 a.m.

I missed meeting strangers from across the globe in hostels, visiting random bakeries and bookstores everywhere I went, the warm breeze on my face when the tube pulled into the station, getting Trinidadian food at Fish, Wings & Tings and the taste of Amsterdam’s fries and mayonnaise.

I mourned the liberation I felt sharing the most vulnerable sides of myself.

I reflected.

I don’t even remember the day I stopped using a map to navigate the Underground. It happened naturally. Nor did I remember when I became so comfortable with myself and able to hold my head so high.

On my first day back at UCLA, I turned 20.

“I thought that I would feel some sort of weight from departing from this era. I felt the weight of turning from 17 to 18. However, that teenage naivety has shed … I think it’s because I allowed the kid in me to have his last hurrah … I leave this chapter behind me with no regrets,” I wrote April 1.

Adjusting back to American life was surprising – and difficult. People talk about the culture shock of moving to a new place but never mention the reverse shock you experience when returning to where you started.

I left England with a different disposition than when I arrived – one very serious, unsmiling and pessimistic.

I had to relearn simple things like American lingo and mannerisms, the taste of preservatives in food and which way to look before crossing the street.

I missed Europe’s architectural aesthetic and the ease of public transportation. I often thought about London, the friends I made and our adventures.

But I realized the adventure would only end if I let myself fall into those same old habits.

They were only a text away, and because we were all attending UC schools, visiting wasn’t difficult. I traveled to Davis and San Diego – parts of California I rarely see – to visit my friends and meet their friends and roommates.

I entered unfamiliar social spaces surrounded by people I didn’t know. Instead of feeling socially awkward and shrinking within myself, I found myself easily engaging, whether it was a house party during Davis’ Picnic Day or playing poker with my friend’s fraternity brothers in La Jolla.

I joined in on conversations, sharing stories and laughing along, or simply sat back, feeling content and at ease in my own company.

Being proactive and grounding myself in the present, I made new memories with the same people over 5,000 miles from where the good times began, bringing out the pieces of myself I thought I left behind in London.

My time abroad is now a distant but wonderful recollection.

And when I miss London, at least I can grab an OK cup of tea and a chocolate croissant at the new Pret A Manger in Westwood.