“Forever chemicals” reported in study spark concern for the incarcerated

By Amy Wong

April 22, 2024 10:56 p.m.

This post was updated April 23 at 10:03 p.m.

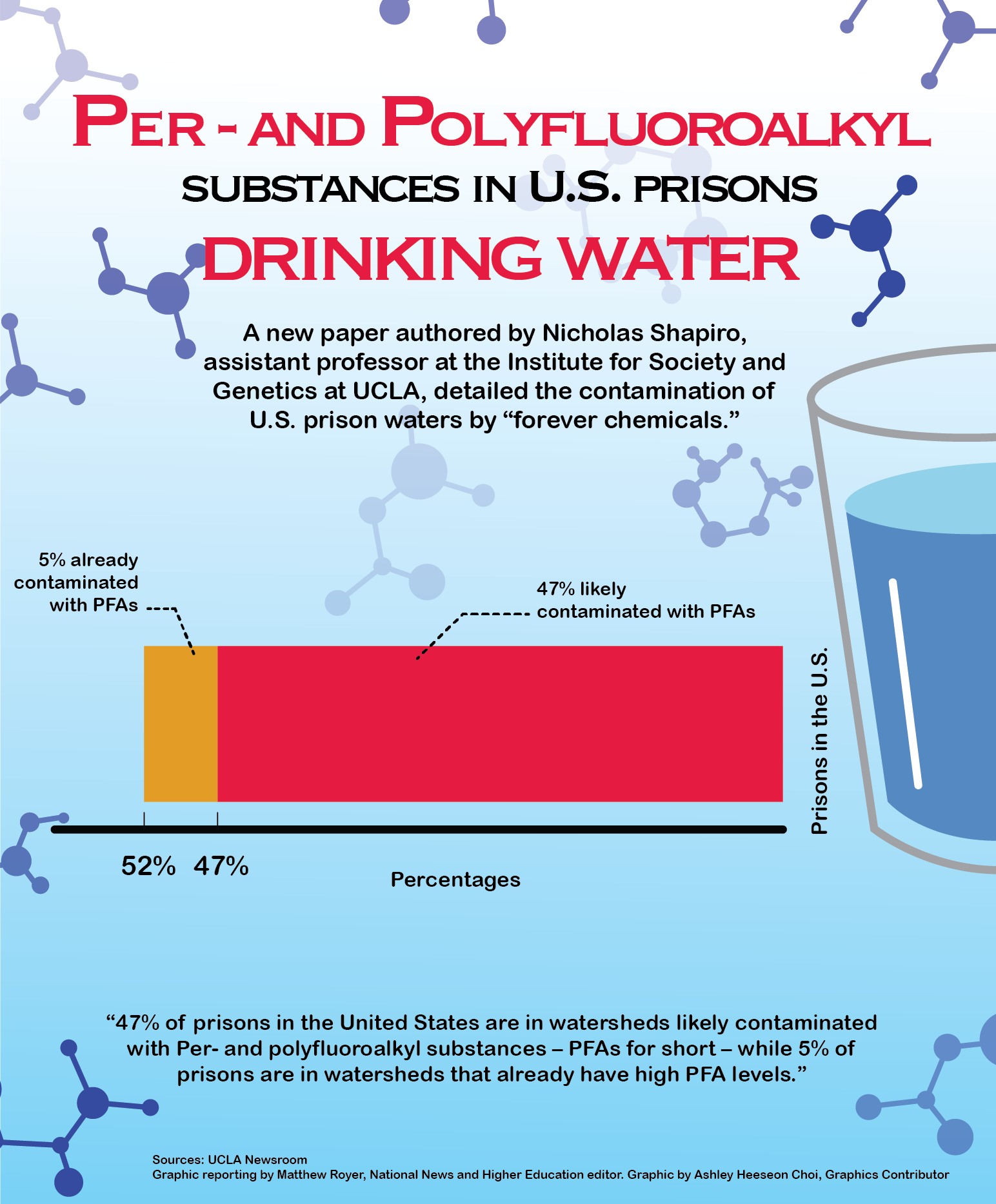

A paper co-written by a UCLA professor revealed high potential exposure rates of dangerous chemicals in United States prison water.

A study published in May 2024’s edition of the American Journal of Public Health found that 47% of carceral institutions were located in a watershed boundary that is in the same boundary and a lower elevation level than a site with per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances, said Lindsay Poirier, a co-author of the paper and an assistant professor of statistical and data sciences at Smith College.

PFAs are a category of chemicals often used in products such as firefighting foam and nonstick pans because of their water-resistant properties, Poirier said. These chemicals are sometimes referred to as “forever chemicals” because human bodies are unable to break them down, Poirier added.

PFAs have been used since the 1940s and are extremely persistent in the environment because they do not break down well, said Nicholas Shapiro, an assistant professor at the UCLA Institute of Society and Genetics. He added that they are also dangerous to humans.

“They cause a broad range of health impacts from birth defects to endocrine disruption,” Shapiro said. “These are chemicals in common household products but also used in industry, and they’re everywhere, almost, so it’s a really big problem. It’s probably one of the most pressing, emerging toxic issues in the world.”

Shapiro said he began to consider studying prison water several years ago after he was called into a community in south Georgia to investigate air quality concerns. The community was farther away from the emission source than the state prison, county jail and a juvenile detention center, he said.

Shapiro also said he noticed that the carceral facilities were located next to an airport that potentially used PFAs, leading him to wonder if the prisons had issues with the chemicals.

The proximity of detention centers to potentially pollution-generating industrial facilities is a pattern that spans the entire country, Shapiro said. He added that he began reaching out to incarcerated people and realized water quality was one of their most common concerns.

Incarcerated people are vulnerable to issues with water quality because they are not able to access alternative water sources, Shapiro said.

“In a free world, it’s much easier for us to get a bottle of water or get a filter, because we have agency over our lives to a degree that’s just not possible in a carceral facility,” he said.

In addition to their lack of options, incarcerated people do not know and are often not informed that their drinking water may be contaminated, Poirier said.

“There is a real need to raise awareness of these kinds of issues so that incarcerated individuals have the ability to advocate for themselves and so that other organizations have the ability to help advocate,” she said.

The main legal protection against contaminated prison water comes from the Eighth Amendment’s prohibition on cruel and unusual punishment, which the Supreme Court ruled to apply to prison conditions, said Sharon Dolovich, a professor of law and director of the UCLA Law Behind Bars project.

Claims about prison conditions under the Eighth Amendment follow the standard of deliberate indifference, or knowingly failing to mitigate situations in which incarcerated people might be at risk, Dolovich said. She added that although there are many organizations which provide legal representation for incarcerated people, there are not enough lawyers to cover Eighth Amendment cases.

On April 10, President Joe Biden’s administration issued a national drinking water standard that included limits on five PFAs known to be in drinking water. Shapiro said the new regulations will increase the number of systems that are tested for PFAs chemicals from 6,000 to 66,000.

“Because of this new rule set, … we are likely going to see much better national data,” Shapiro said. “In a few years, we’re going to be able to really understand, and even in a much more granular level, the actual exposures that are happening across the country.”

One of the challenges the researchers faced when writing the report was the lack of monitoring of PFAs in different parts of the country, Poirier said.

Differences in monitoring techniques and policies across states also made data difficult to analyze, Shapiro said. The researchers used statistical modeling to smooth out differences between environmental regulatory jurisdictions in an attempt to get a broader picture of risk exposure to incarcerated individuals, he added.

The high exposure to PFAs is indicative of the flaws of the carceral system, Shapiro added.

“We need the data to step into the truth,” Shapiro said. “But we also need to think about this issue as not just a water quality issue, but the issue of the unsustainability of the way that we do incarceration in the U.S.”