The Future: Utopian fiction preserves hope in media saturated with violent, dark narratives

(Rama Das/Daily Bruin)

By Nicolas Greamo

May 4, 2023 9:24 p.m.

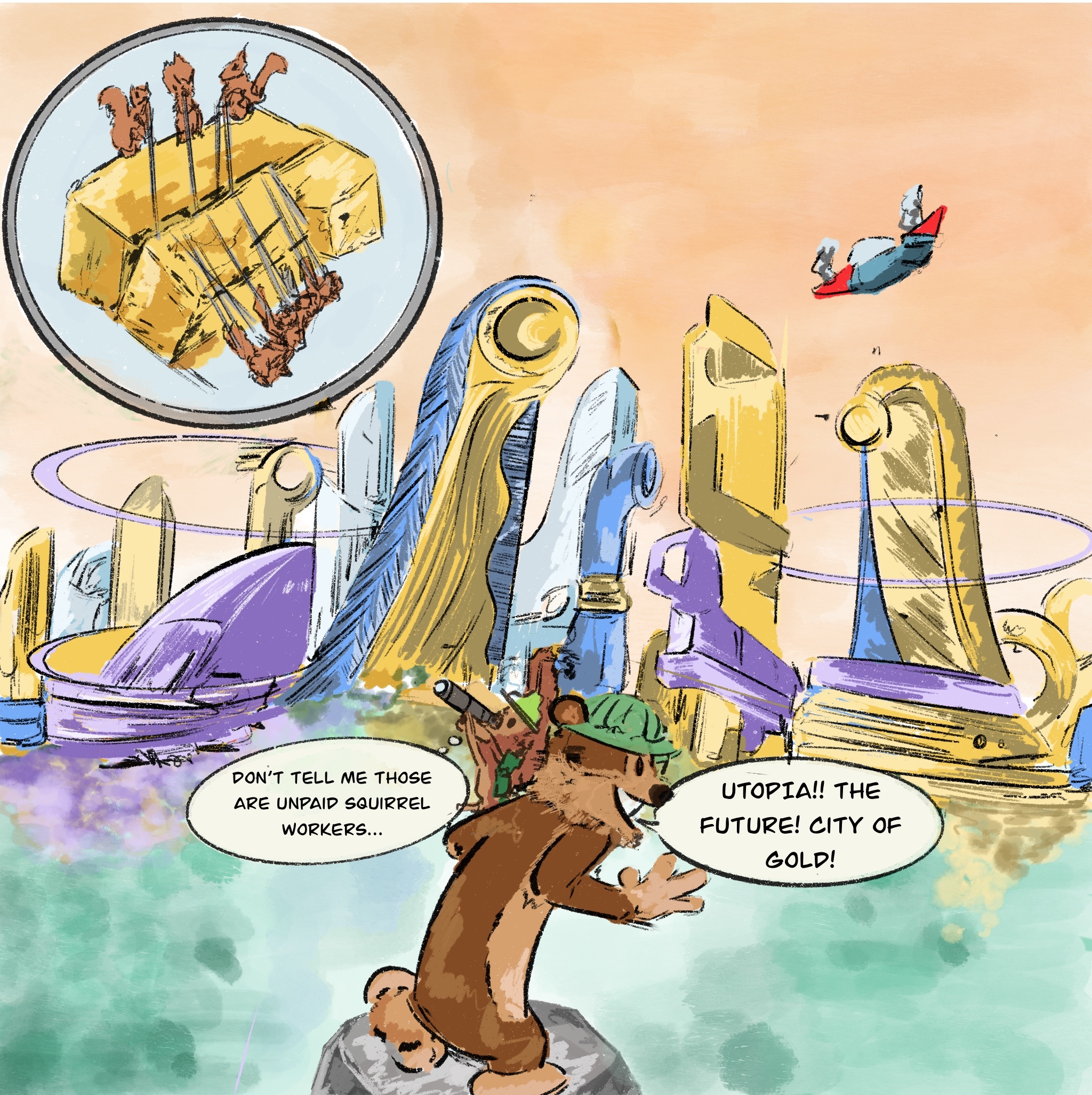

When was the last time you saw a piece of science fiction depict a future you actually wanted to live in?

Maybe there’s the idealized version of 2015 in “Back to the Future Part II” that Marty McFly visits, complete with hoverboards and a 19th movie in the “Jaws” franchise. Ultimately, however, this ideal 2015 disappears when his father’s high school bully steals a future sports almanac to become a massively powerful Donald Trump-inspired casino mogul in the 1980s, then making preparations for a presidential run.

The actual best example is probably “Star Trek,” which showcases a pretty progressive view of a moneyless global human community under a single government that has established a mostly peaceful federation of planets by the 22nd century.

However, beyond these rare examples, most science fiction properties today tend not to embrace utopian visions of the future.

Our pop culture is dominated by dystopias.

From “The Hunger Games,” set to release a prequel film in November, to the TV show “The Last of Us,” to James Cameron’s “Avatar” franchise, our cultural conception of humanity’s future seems overwhelmingly bleak.

Beyond the recent examples, of course, are the lengthy list of dystopian films which have transformed our society and politics forever. We have used “1984” so much to signify something authoritarian or totalitarian that it has almost completely lost all meaning, which is fitting considering the point of Orwell’s novel.

Or consider the cultural stranglehold that “The Matrix,” a sci-fi allegory for the transgender experience created by two trans siblings, has on both our conception of virtual reality and our politics. The famous choice Laurence Fishburne’s Morpheus offers between the “blue pill” and the “red pill” has been appropriated by online reactionaries, even when the color of the red pill is specifically a reference to the color of estrogen pills.

To some extent, imagining a future of failure, suffering and apocalypse is simply a reflection of our society’s existential dread, first driven by the threat of nuclear war and now climate change.

But the fact that so much of our cultural output seems so pessimistic about our future has the potential to actually cement a nihilistic attitude of the future and an antipathy toward the present.

Believing that we have no hope to ever change the course of our future plays directly into the hands of those most responsible for the rising carbon emissions that threaten our existence or the massive military-industrial complex that benefits so much from designing deadly weapons and the auxiliary systems needed to deploy them.

If we don’t believe in the possibility of a better future, what else do we really have?

What is so fascinating about utopian fiction is its potential power to shape the kind of society we want to live in and progress toward.

The utopia is, first and foremost, a political tool. It requires a degree of honesty and clarity in one’s political intentions which can often be off-putting, but feels right at home in the field of speculative fiction.

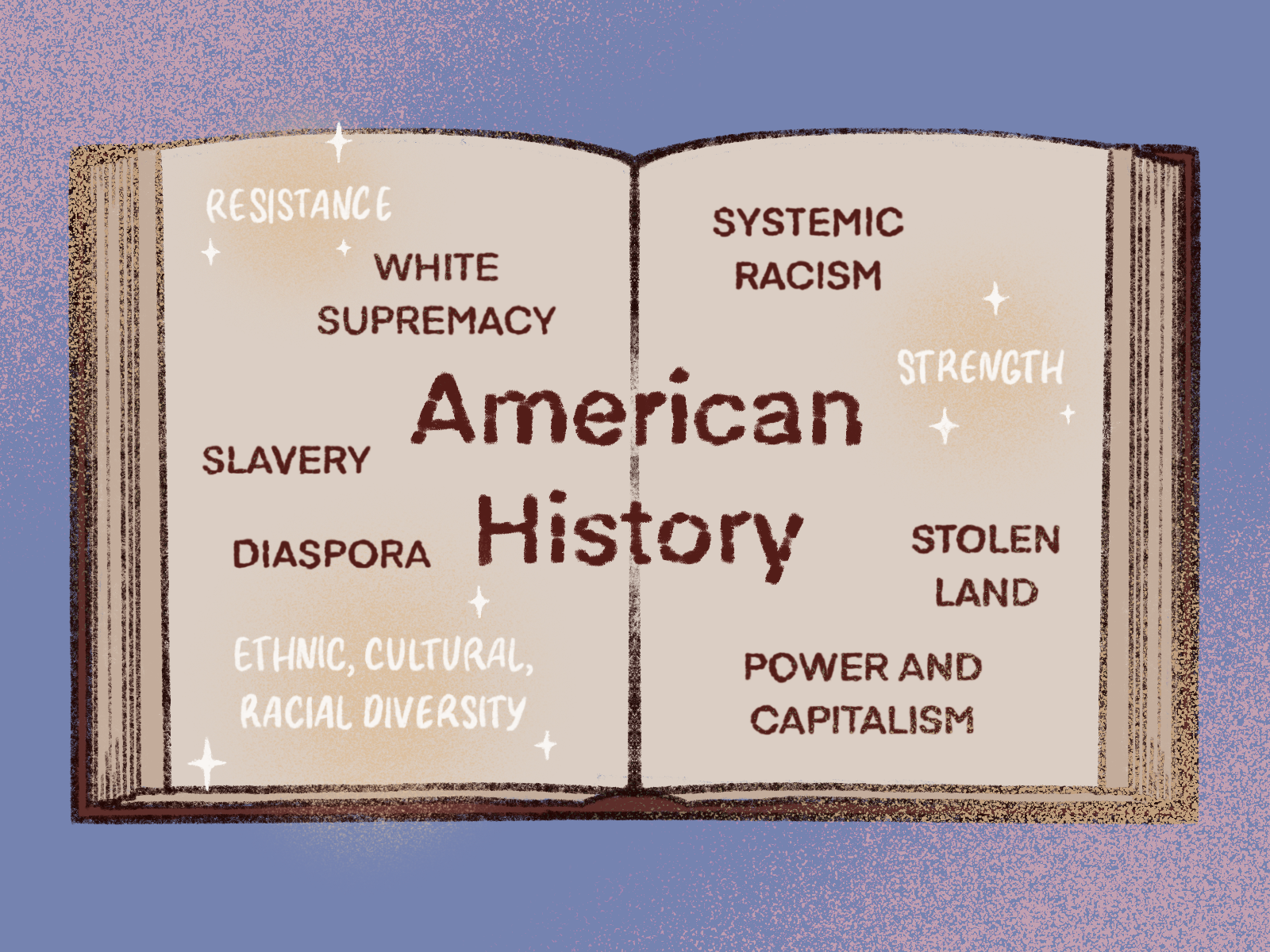

The genre of science fiction has been innately political from its inception. Consider, for instance, the omnipresence of robots in artistic conceptions of the future, stretching from Fritz Lang’s expressionist masterpiece “Metropolis” to Isaac Asimov’s lengthy bibliography to the “Blade Runner” series.

These pieces of fiction, largely made way before the actual technological advances in the field of robotics that we see today, ask questions about whether machines can be human because they reflect how our society so often turns humans into machines.

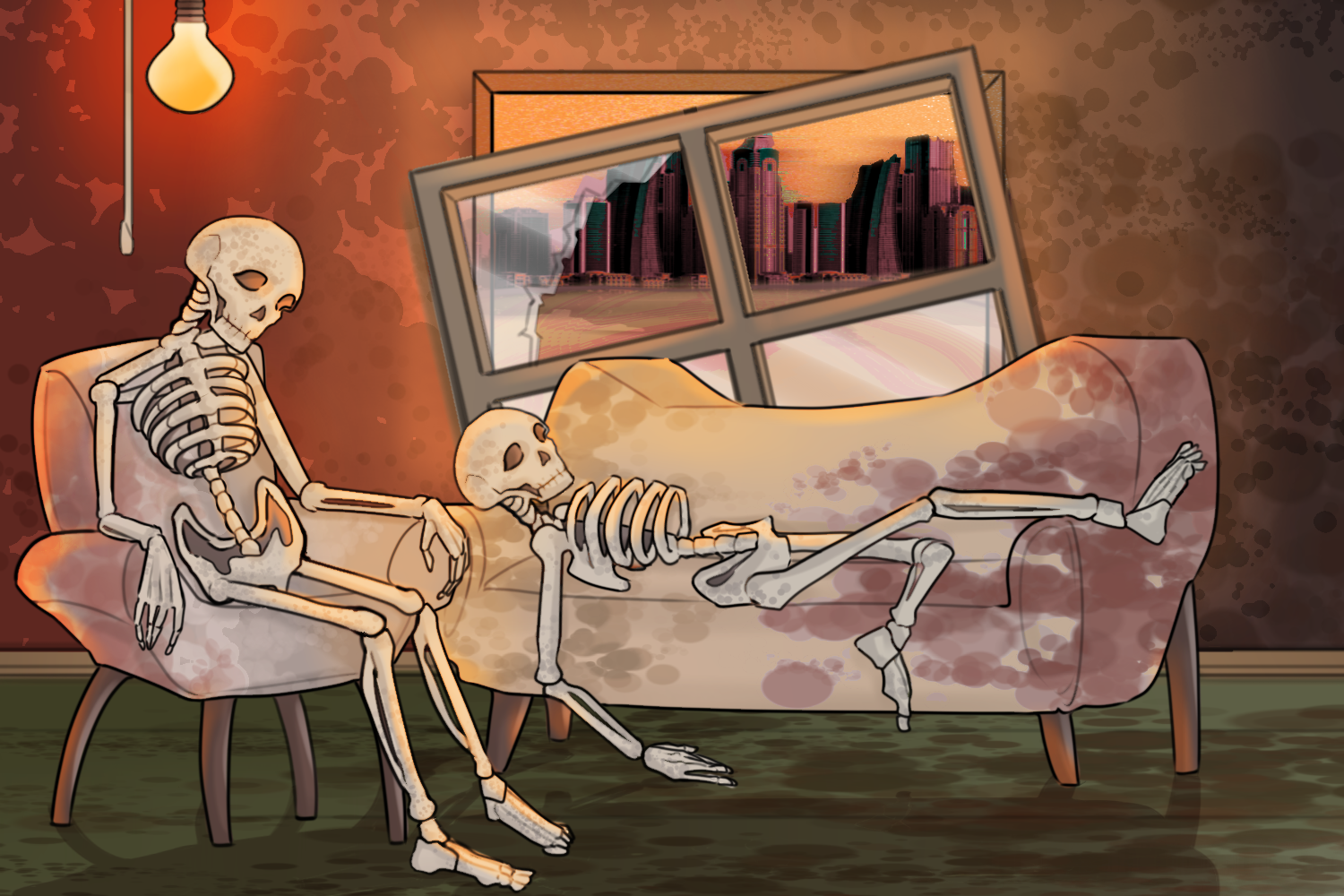

To some extent, our focus on dystopias over utopias is a consequence of how centrally our pop cultural landscape emphasizes the role of conflict and violence as drivers of narrative. This is particularly evident in video games, often accused of causing real-world violence, where the central interaction that the player, inhabiting their game avatar, has with many game worlds is explicitly violent.

We need more utopian fiction. More space-age romances. More worlds to dream of beyond the barren deserts or dark police states that so frequently serve as the settings for the same kinds of dystopian narratives.

Are we not deserving of even a little hope?