The Future: Existential threats must be understood and addressed to navigate future

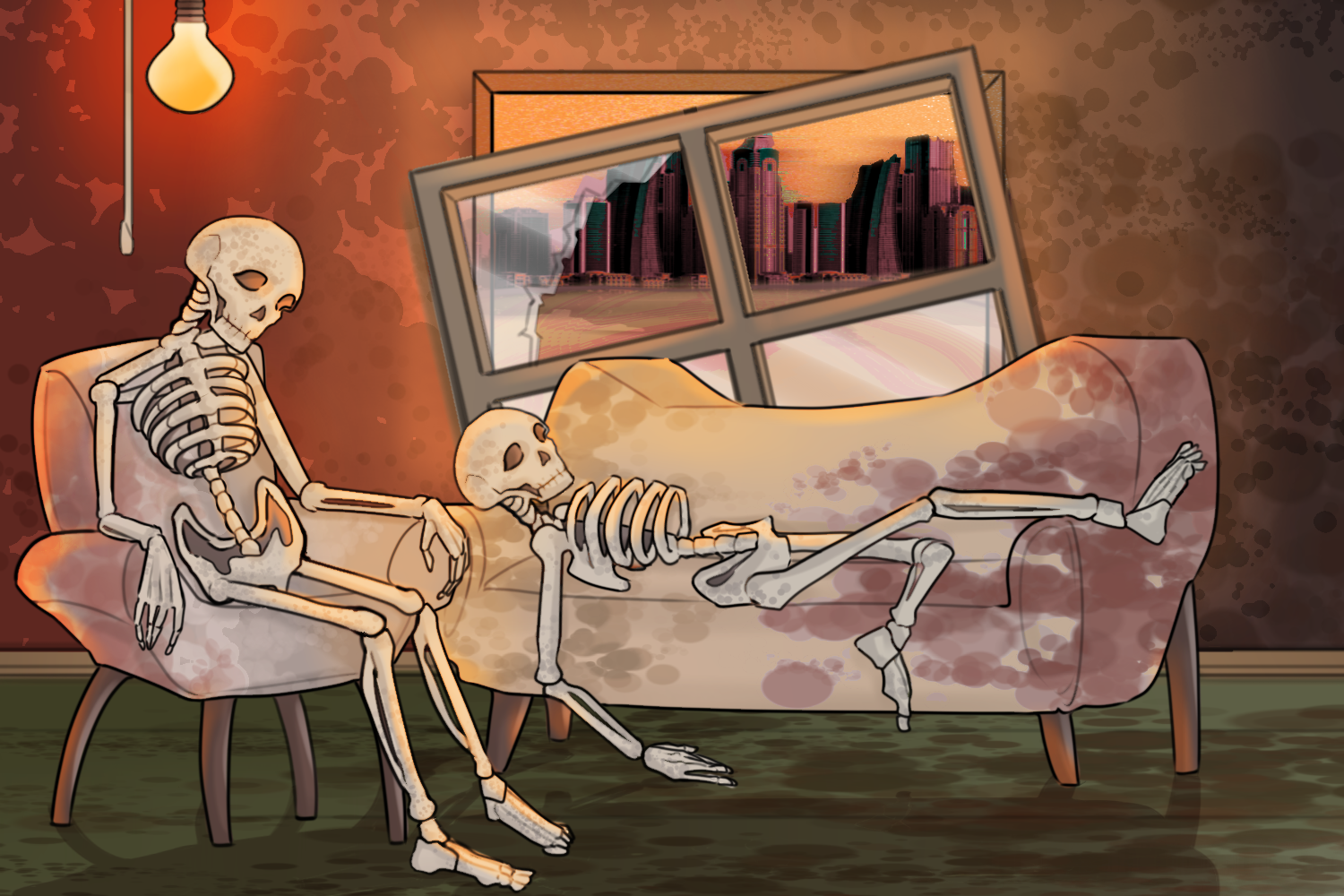

(Yan Liu/Daily Bruin)

By Allison Bushong

May 4, 2023 9:17 p.m.

People across the world have been faced with the seemingly ever-present fears of a global pandemic, climate change, mass shooting threats and international warfare – and that’s just within the past few years.

In order to navigate the future effectively, we need to address and mitigate these existential threats that continue to loom over our heads.

Of course, fears of potentially apocalyptic events occurring in our lifetimes are not new.

During the Cold War, anxieties over a potential nuclear exchange between superpowers helped create a culture of paranoia about communist infiltration that permeated American society. Many of the ways Americans responded to the culture that blossomed from the existential threat of the Cold War and the Red Scare in the 1950s set a precedent for how we respond to foreign policy threats today.

“There was this overwhelming sense of fear,” said Thalia Ertman, a doctoral student in the department of history. “Some of this still holds over. If you are considered an employee of the University of California, one of the things you have to do when you become an employee is sign a loyalty oath, which is straight out of the Cold War.”

There are clear parallels between the nuclear fears of that period and our generation’s reaction to the climate crisis, which has driven the rise of eco-anxiety. According to Narayan Gopinathan, a doctoral student at the Institute of the Environment and Sustainability, eco-anxiety is the fear and worry associated with the damaging consequences of human activities on ecological systems.

Eco-anxiety can create a culture of fear about the future of our planet, similar to the feelings collectively experienced by Americans in the 1950s. As we grow up in a world where existential threats pervade our lives, we get almost acclimated to them as their presence becomes normalized.

Sean Yancey, a psychiatry fellow at UCLA Counseling and Psychological Services, recounted a 2021 study by The Lancet that found that 84% of youth are at least moderately worried about climate change. About 56% of the respondents in the study agreed with the statement that “humanity is doomed” because of climate change.

Despite this, Yancey added that very few UCLA students seek counsel from CAPS regarding their eco-anxiety.

“I don’t feel like I actually encountered that much eco-anxiety in the clinic,” said Yancey. “Part of it is it’s this really abstract thing. It’s hard to know: ‘How do I even think about this? How do I worry about this? Who do I tell about this?’”

Similarly, everyday citizens living through the intense paranoia and fear that was cultivated during the Cold War may not have turned their full attention toward these seemingly imminent threats to their existence. The lack of direct attention to these anxieties does not make them any less real. In fact, this indicates a deeper understanding of how we respond to existential threats when they seem pervasive.

Ertman compares 1950s instructional videos showing kids how to hide under their desks in the case of a nuclear threat to the active shooter drills that have been implemented in public schools for several decades. For Generation Z, these drills became more routine than explicitly fear-inducing.

“That was very normalized,” said Ertman. “In some ways, it’s this constant low-level awareness that there is a threat, but it’s also not as shocking as we might think it is.”

The massive media coverage these crises garner often desensitizes us to them. Witnessing a mass shooting every other week on TV only normalizes the tragedy and diminishes the intrinsic value of human life in the process. Perhaps this continued low-level awareness of threats to our existence, perpetuated by their presence in the media, contributes to Gen Z having some of the highest levels of depression and anxiety ever recorded.

On an individual scale, dealing with these mental implications can be difficult, but not impossible. Alongside the techniques of mindfulness and setting individual boundaries with news consumption, Yancey advises collective action as a way to confront these anxieties. When turning toward the future, understanding the unexpected impact that these low-level anxieties can exert on our lives is integral to building resilience and making permanent changes.

Ertman sees some of these existential crises as motivators for social change. She gives the example of the 1960s counterculture, the Women’s Liberation and Civil Rights movements having branched out of the extreme paranoia of the 1950s. This follows a similar pattern to the 2020 social justice movements such as Black Lives Matter and Stop Asian Hate arising against the backdrop of the pandemic.

“In a nihilistic way, you’re like, ‘Well, then we don’t really have anything to lose, so we might as well pay for what we believe in,’” said Ertman. “I have hope that there will be more protests and more actual change done.”

Gopinathan echoed Ertman’s hope for collective action in the future, pointing out that there are individual and collective moves we can make to mitigate the anxieties that may plague us.

“I do think that we can be proactive by engaging in activism, engaging in personal action to try and help this transition (away from fossil fuels) happen faster,” said Gopinathan. “For example, I think if you’re a citizen of a democratic country, the number one thing you can do is vote.”

As existential threats continue to arise, we must understand our relationships with them and their patterns in history in order to navigate the future on both individual and collective levels.