Op-ed: Untold stories of urban Indigenous women need to be heard

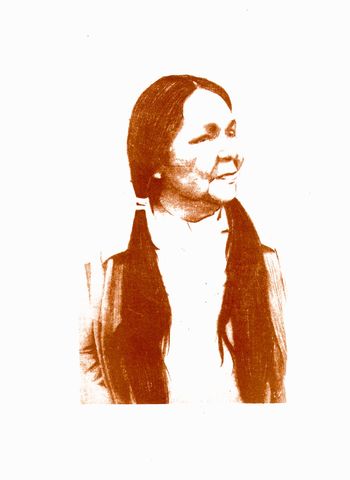

UCLA assistant professor Kyle Mays shares the story of his great-grandmother Esther Shawboose Mays, a fierce advocate for Indigenous peoples in Detroit. (Courtesy of Kyle Mays. Illustration by Liseth Amaya.)

By Kyle Mays

Nov. 25, 2021 10:58 p.m.

This post was updated Nov. 29 at 9:45 a.m.

The experiences of urban Indigenous communities remain understudied and misunderstood. I want to tell the story about the importance of Indigenous women in postwar Detroit. In the spring of 1940, my Nokomis, or great-grandmother, named Keadnoquay, or Esther Shawboose, traveled to Detroit from the Saginaw Chippewa Reservation at the age of 16. Detroit was right on the precipice of becoming the arsenal of democracy because of its contribution to the United States’ World War II efforts. I’m sure she was terrified. Imagine coming to a large city without family as a teenage girl and trying to survive.

Not long after she settled in Detroit, Esther married an African American man, my great-grandfather, Isiah Mays. They would go on to have nine children. While many Indigenous peoples migrated to cities in the 1940s and 1950s because of federal urban relocation policies designed supposedly to usher in Indigenous peoples from the savagery of their reservations to the civilized city, she came on her own accord.

She understood that in order to thrive, she needed to be around other Indigenous peoples. So, she joined the North American Indian Association, which first opened in 1940 as a hub for Indigenous peoples from Canada and all of the U.S. to immerse themselves in community and culture. As more and more Indigenous peoples came to Detroit, they began to protest their constant status as an invisible minority in an increasingly all-Black city. And protest she did, especially on behalf of children.

She founded a nonprofit, Great Lakes Northern Stars, which was designed to keep Indigenous youth in the homes of the Indigenous community. And she made sure that her children were involved in activism from the time they could crawl. She also co-founded Detroit’s Indian Educational and Cultural Center in 1974. This federally funded program was designed to educate youth in Indigenous cultures and make sure that they had an education that centered their histories and perspectives. She understood that urban spaces were an important part of the future of Indigenous peoples, and without creating educational institutions for youth, the future would not be bright.

She would continue protesting and working to create cultural and educational opportunities for Indigenous youth throughout the state of Michigan. She worked tirelessly with other Indigenous leaders to get the Michigan Indian Tuition Waiver, which granted Indigenous students who wanted to attend public colleges or universities free tuition based on treaty obligations, passed in 1976.

Esther died in 1984. However, her daughter, my aunt Judy Mays, continued working toward her mother’s dream – the creation of an all-Indigenous school to educate young people in the urban environment. My aunt Judy would go on to found the Medicine Bear American Indian Academy in 1994 in the city of Detroit. It was the third ever public school with an Indigenous curriculum.

While my family’s legacy as activists and cultural and educational workers is important, it is not unique. There are likely hundreds of stories of Indigenous women working to make urban spaces tolerable places for Indigenous youth to thrive. I end this by saying we should revive these legacies and continue to bring to light the many stories of urban Indigenous histories as well as the many forms of activism that urban Indigenous communities continue to demonstrate, showing that they are here and will continue to be so well into the future.

Mays (he/his) is an Afro-Indigenous (Saginaw Chippewa) writer and scholar. He is an assistant professor in the departments of African American studies, American Indian studies and history at UCLA. He is the author of “Hip Hop Beats, Indigenous Rhymes: Modernity and Hip Hop in Indigenous North America” (SUNY Press, 2016) and “An Afro-Indigenous History of the United States” (Beacon Press, 2021). He has a forthcoming book, “City of Dispossessions: Indigenous Peoples, African Americans, and the Creation of Modern Detroit” (University of Pennsylvania Press, 2022).