International students face challenges with COVID-19 vaccine accessibility

By Anya Sastrena

May 13, 2021 11:24 a.m.

About 6,000 miles away from Westwood, Hana Hong sees all her UCLA friends posting their COVID-19 vaccination cards on Instagram.

Although Hong wants the vaccine, the first-year biology student from South Korea said she has not been able to receive the first dose.

“I have no access to them,” she said. “My mom has no access to them.”

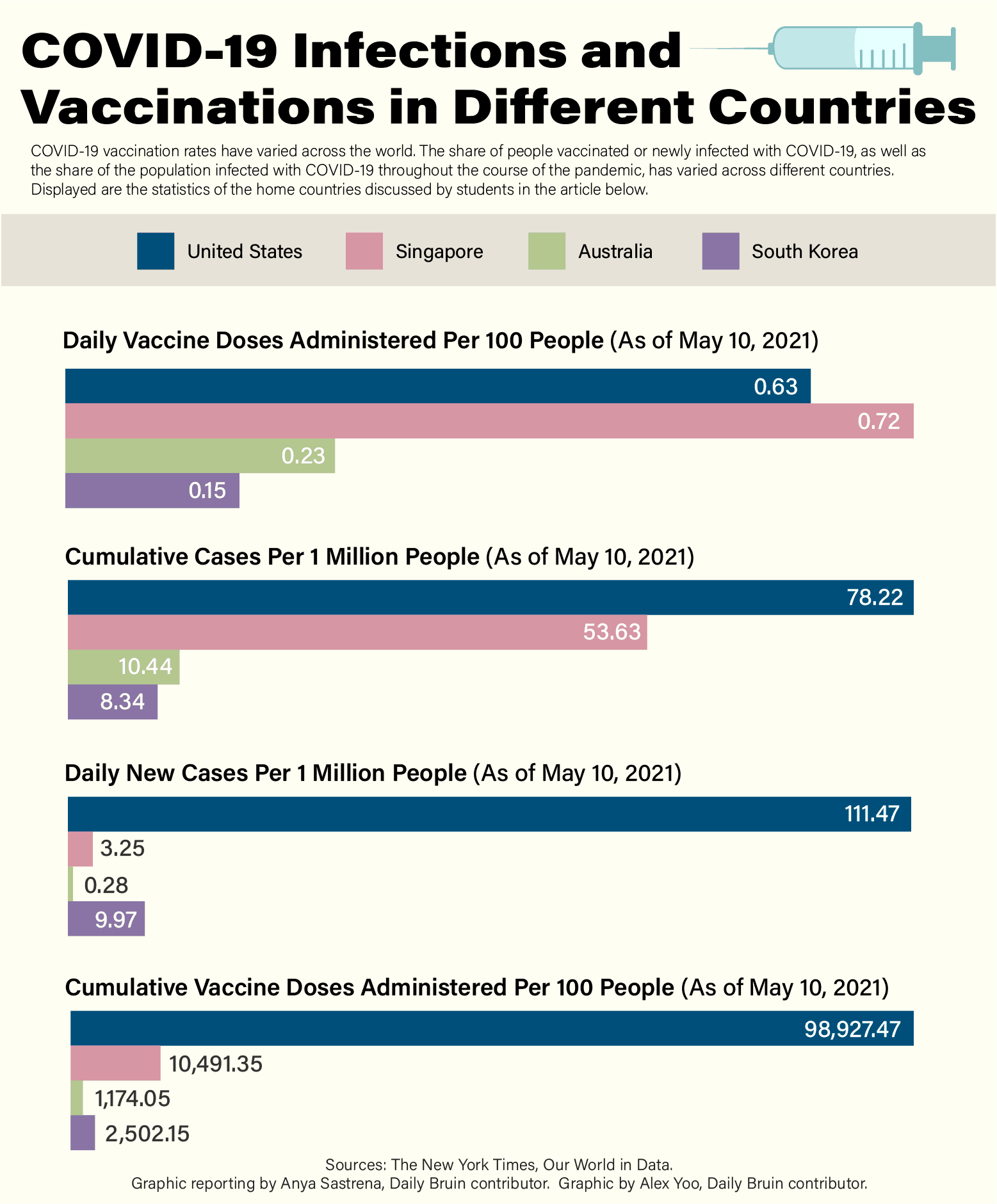

Despite the U.S. reaching a highest single-day total of 300,000 new cases in one day in January, COVID-19 cases have dropped over the last few months because of an accelerated vaccine rollout within the country, according to University of Minnesota’s Center for Infectious Disease Research and Policy.

In the U.S., over 150 million people, or 46% of the population, have received at least one dose of the COVID-19 vaccine, and over 100 million people are fully vaccinated, according to USAFacts.

However, some nations that had a comparatively more effective initial COVID-19 response now have slower vaccination distribution rates, leaving some international students frustrated with their respective home countries’ situations.

According to the Korea Disease and Prevention Agency, 3 million of the 51 million South Koreans have been able to receive at least one dose of the COVID-19 vaccine, and less than 200,000 residents have received both doses.

Being unvaccinated and taking extra health precautions led Hong to miss out on opportunities she said she felt were essential to the college experience, such as making friends and experiencing the notorious freshman 15.

“There are so many things that I wish would have happened during this first year of university,” she said. “And seeing some friends being able to spend time with the people they love. I’m so envious”

[Related link: Remote environment leads to feelings of disconnect for first-year, transfer students]

In April, The University of California released a proposed plan that requires all UC campuses to have vaccinated students and employees for the upcoming fall quarter. If students are unable to access a vaccine, the student health center may help students find available vaccines in nearby locations.

Despite these campus vaccination efforts, international students still face challenges with the current vaccination progress in their home countries.

Some international students residing in the U.S. are worried their loved ones at home don’t have access to vaccines.

Sydney Stuckmann, a first-year pre-global studies student from Australia, recently received her second dose of the Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 vaccine. However, her parents, who are both around 50 years old, must wait until July to receive their second doses.

“There’s a huge waiting period between your first vaccine and the second,” she said.

Stuckmann said she thinks tightening regulations because of slow vaccination rates may pose financial challenges for Australian families living outside the country. Because of costly hotel quarantine requirements, Stuckmann said many of her family friends have not been able to return home for over a year.

Since March 2020, Australian passport holders and permanent residents returning to the country must quarantine in a government-approved hotel for 14 to 24 days. These rooms cost around $2,330 USD per room, according to CNN.

Christine Nam, a first-year sociology student from South Korea who currently lives in Los Angeles, is also concerned about her family at home.

“I feel really bad personally because I’m here in LA fully vaccinated while my grandparents, my parents, my relatives, they’re not getting vaccinated and they probably won’t get vaccinated for who knows how long,” she said.

Nam said she started feeling guilty and frustrated, especially since South Korea had a more robust initial response to the COVID-19 pandemic. She added that people living in South Korea had been taking greater safety precautions and had given up more of their freedom compared to those in the U.S.

When Nam went home to South Korea during winter break, she experienced strict safety protocols, such as regular phone checks, to ensure she was properly quarantined for two weeks.

“It’s just frustrating to know that we took the correct measures,” Nam said. “But, you know, superpowers like the U.S. will always be able to get their hands on the vaccine and stuff faster.”

[Related link: Removal of states’ mask mandates exposes students to anxieties, public scrutiny]

Christina Ramirez, a UCLA biostatistics professor, said the consequences of a slower vaccine rollout in countries outside the U.S. is that eventually people will want to travel, and all countries will feel the need to open their borders.

“Well if they can keep the cases out, then (other countries) should be okay, but eventually you’re going to have to open your borders,” she said. “The virus isn’t going to be held at bay forever.”

Ramirez said she is also concerned that the inequity of vaccine distribution around the world could create a “two-class society,” in which there exists a divide between those who are able to access vaccines and those who are not.

It would take approximately 4.6 years for herd immunity against SARS-CoV-2, the specific virus causing COVID-19, to be achieved on a global scale, according to the New England Journal of Medicine.

“We also need to think through all of the outcomes. … Are we creating a two-class system?” Ramirez said. “Are we marginalizing and stigmatizing people of color? Or people who don’t have the resources to get these vaccines?”