UCLA professor sheds light on Indonesian anti-communist purge in upcoming book

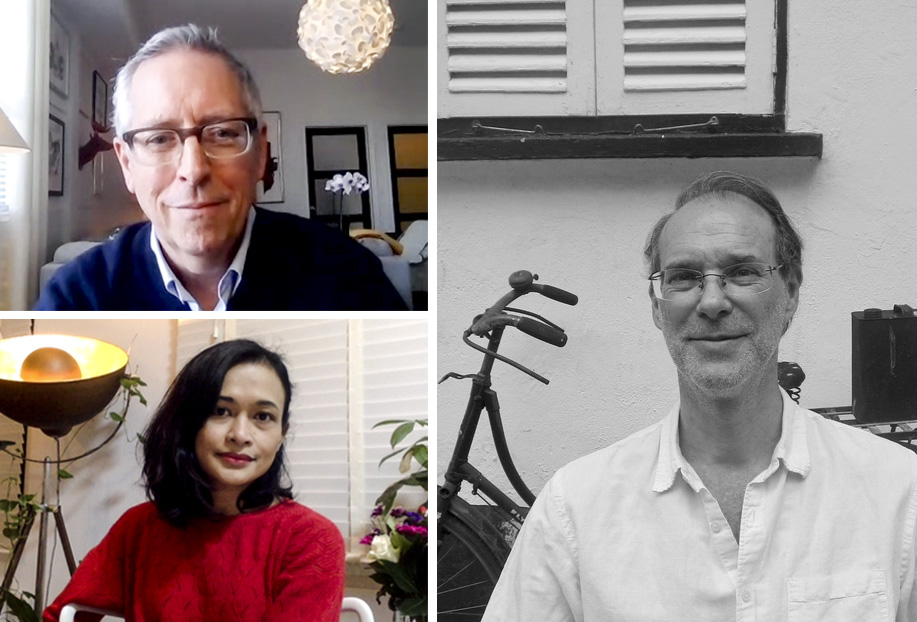

Co-authors Geoffrey Robinson (top left), a history professor at the UCLA Center for Southeast Asian Studies, and Douglas Kammen (right), a Southeast Asian studies associate professor at the National University of Singapore, have been building a visual archive of Indonesia’s 1965-1966 anti-communist purge since 2016. With the help of Belgium-based artist Elisabeth Mulyani (bottom left), they have collected around 2,000 images. (Clockwise from top left: Ariana Fadel/Daily Bruin, courtesy of Dr. Kammen, Ariana Fadel/Daily Bruin)

By Constanza Montemayor

Jan. 12, 2021 8:08 p.m.

This post was last updated Jan. 16 at 5:58 p.m.

Some Indonesians have been moved to tears when they learn about the true history of mass violence in their country, said Elizabeth Mulyani, an Indonesian artist based in Belgium.

Mulyani is working with Geoffrey Robinson, a history professor at the UCLA Center for Southeast Asian Studies, to build a visual history of the mass violence of the mid-1960s in Indonesia.

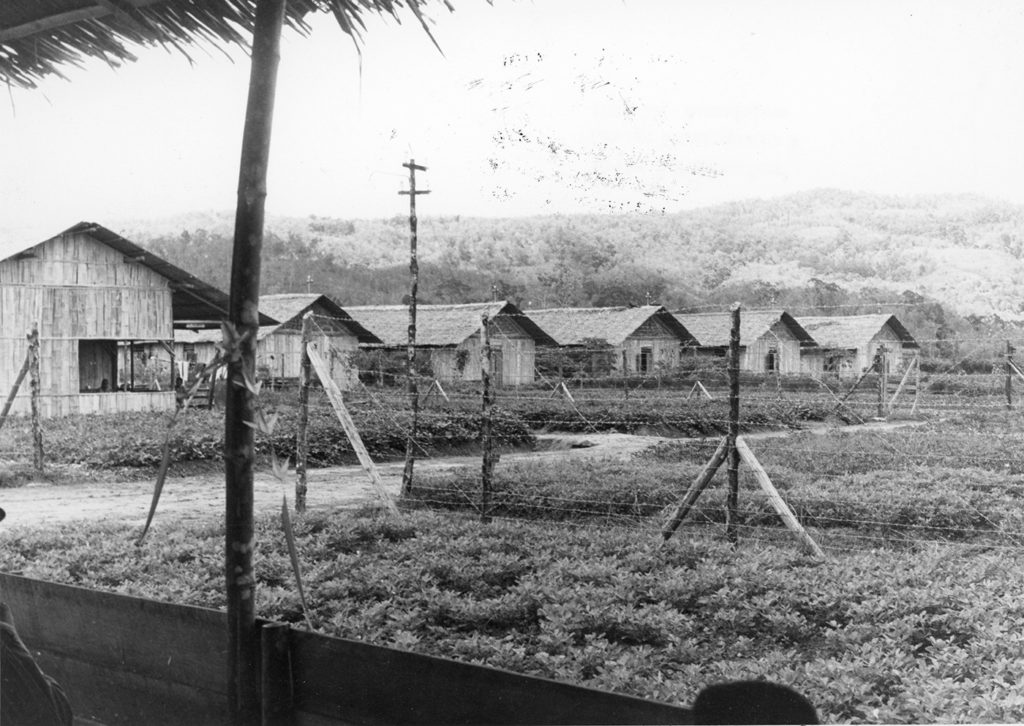

For the last four years, Robinson has worked with Douglas Kammen, a Southeast Asian studies associate professor at the National University of Singapore, on a book to document Indonesia’s 1965-1966 violent anti-communist purge through photographs, historical documents, political cartoons and military posters.

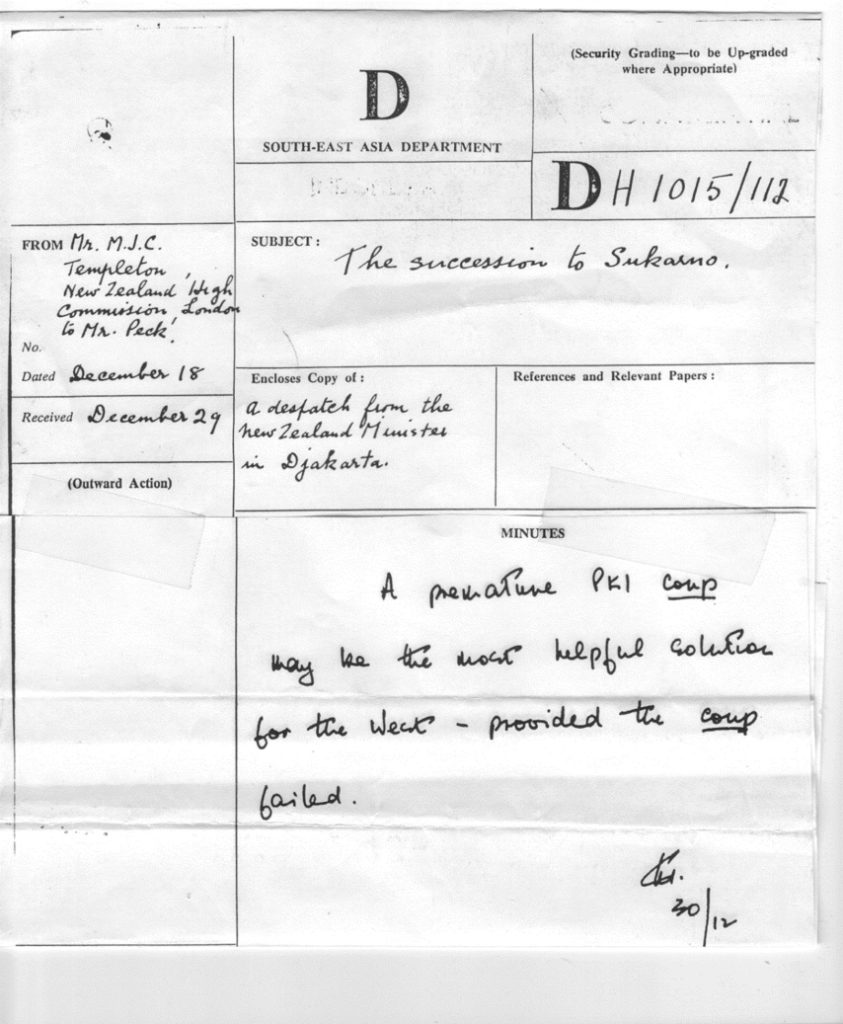

The violence was triggered when officers in the Indonesian army killed six generals on Sept. 30, 1965, which the government blamed on the Partai Komunis Indonesia, the country’s communist party. The insurrectionists referred to themselves as the Sept. 30 Movement, or G30S. In the following months, the army killed at least 500,000 and jailed another one million Indonesians for their actual or alleged ties to the PKI.

Robinson said he hopes this new book focused on images will serve as a visual archive of the turbulent years of 1965 and 1966 and help scholars and Indonesians build a collective memory of the violence. Indonesian authorities have previously censored public discussion of the mass violence and justified the massacre.

His last book on the same subject, “The Killing Season: A History of the Indonesian Massacres, 1965-66,” won the 2019 Raphael Lemkin Book Award by the Institute for the Study of Genocide.

Robinson and Kammen collected around 2,000 images with the help of many people across the world, from Singapore to Belgium. They hope to publish the book in the United States and Indonesia within the next two years, with about 300 images with limited commentary and few depictions of graphic violence.

The first draft is nearly finished, and they expect to find a publisher within the next few months, Robinson said.

To compile materials for the book, Robinson and Kammen researched and contacted foreign and local journalists who had been in Indonesia. They also collected amateur photographs from Indonesian families, official photographs from the army and images from newspapers.

Finding new sources to work with is uniquely exciting to historians, Robinson said.

During the project, he got a call from New York to talk to a potential source: Beryl Bernay, a former American journalist, television personality and communications official at the United Nations who frequently visited Indonesia during the 1960s.

Dahlia Setiyawan, a social studies teacher who graduated from UCLA in 2014, helped Robinson track down Bernay for the project and traveled to New York to retrieve the relevant photographs and interview Bernay, who died of COVID-19 in March.

Bernay gave the team pictures and film reels of her encounters with civilians and politicians from 1965 to 1966, including meetings with the first president of Indonesia, Sukarno, and with Kesatuan Aksi Mahasiswa Indonesia, an anti-communist student group.

“You’re really looking at something that’s consequential,” Setiyawan said. “You don’t have to be a historian to connect with a photograph, to really look at something and see something that you want to know more about.”

Robinson and Kammen reviewed each image in the book, using their historical expertise to select the best images to illustrate the history of mass violence in Indonesia. They also enlisted the help of Mulyani to analyze artistic elements of the images, such as a photograph’s lighting and composition.

Before the COVID-19 pandemic, Robinson said he met with Kammen and Mulyani in Singapore or Los Angeles to discuss final selections for the book. Now, discussions occur online.

“You can’t go out for lunch and you can’t sit down over a cup of coffee for four hours and just toy around with things and flip photographs across the table,” Robinson said. “It’s just not the same, especially if you’re a kind of older, die-hard, analog kind of person…I don’t feel as totally comfortable with doing everything digitally and remotely.”

The idea for the project emerged when Kammen stumbled upon a collection of images that puzzled him: photographs related to the 1965 to 1966 mass violence stamped with the brands of French magazines.

This, Kammen said, prompted him to compile images related to the massacre and later contact Robinson, who Kammen had previously met and thought would be a good fit for the project.

“At a certain point, I realized that this was a project that would really be best done in collaboration, largely because I think it’s important to have not one person’s voice droning on – we all have a particular style (and) write in a certain way,” Kammen said.

As an Indonesian, Mulyani said she found this project significant because of her own experience learning the government’s narrative of the mass violence.

Growing up, Mulyani said she watched the government-made film “Penumpasan pengkhianatan G30S/PKI”, which translates to “Eradication of the Treason of the G30S/PKI”, every Sept. 30. The film depicts the Sept. 30 Movement, portraying the PKI as orchestrators of the crime, and depicts the Indonesian army stepping in to defeat the rebels and restore order to the country. The film was part of an annual compulsory screening program in Indonesian schools every Sept. 30 from 1984 to 1998.

It was only when Mulyani left Indonesia after graduating university that she learned more. When she moved to Belgium to study visual arts, she met Indonesian exiles and watched Joshua Oppenheimer’s “The Act of Killing,” a documentary about the mass violence in Indonesia from 1965 to 1966.

“All of a sudden … you could get out of this house and you could see your house from (the) outside, and you could also see that there are other things, not only those walls,” she said. “Everything that you believed in that house, you thought it was the only reality of life, of the world.”

In the same way she left the metaphorical house built around her by the government, Mulyani said she hopes other Indonesians will have the chance to do so through the book.

The book could also bring closure to the victims of the mass violence, Robinson said. As of publication, the Indonesian government has not issued an official apology for the mass violence.

“I hope that it contributes in some way toward the building of a social and historical memory of those events,” he said. “And maybe in that way bring about something closer to a resolution, maybe restitution, maybe justice for the people who died.”