Glove developed by UCLA researchers translates American Sign Language to speech

By Noah Danesh

Aug. 3, 2020 3:40 p.m.

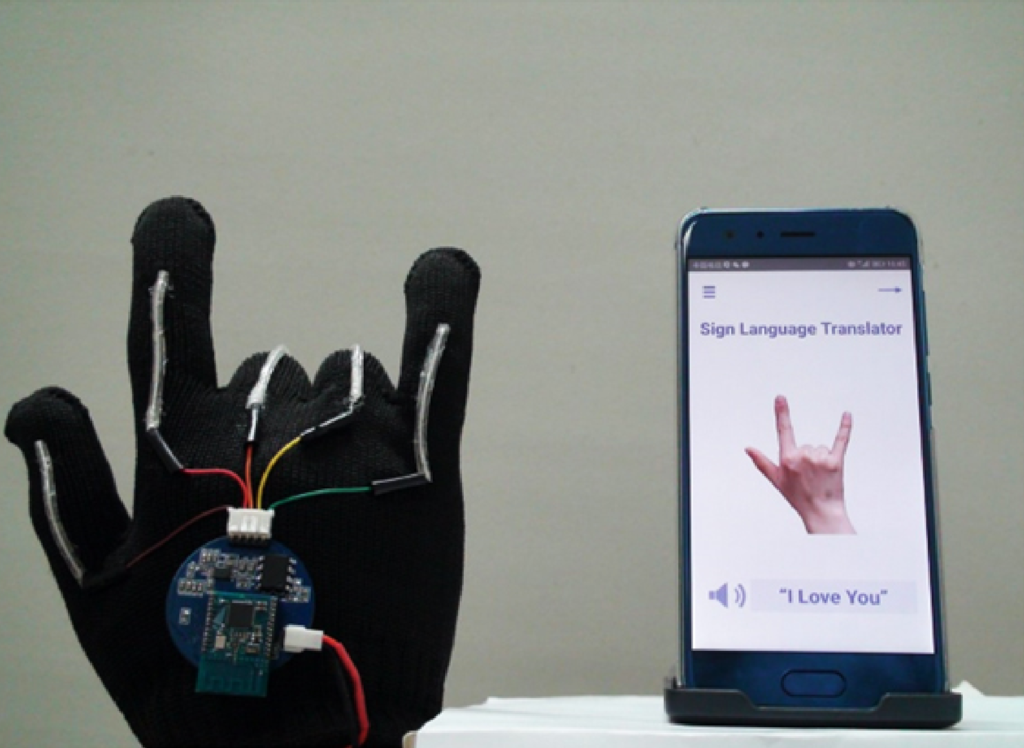

UCLA researchers have developed a smart glove that converts American Sign Language into spoken English.

The glove uses stretchable sensors and a circuit board to wirelessly send signals to a smartphone app – also developed by the researchers – which translates hand gestures into English. The glove can analyze up to 660 different gestures, has a recognition rate of over 98% and is able to translate gestures into speech in less than a second.

(Courtesy of Jun Chen)

Jun Chen, a bioengineering assistant professor who created the glove’s technology, said the glove is more practical and convenient than other technologies that translate sign language.

Other technologies use sensors, which are bulky and inconvenient to wear, or cameras, which are difficult to transport and do not work well in low-light conditions, said Chen, who is also the principal investigator at the UCLA Wearable Bioelectronics Research Group.

The ASL glove has a simple design, weighs about 100 grams – around the weight of a small apple – and costs about $50 to make in a lab, Chen said. With continued improvement and mass production, the cost of production could decrease, he added.

People have given positive feedback for the glove so far, Chen said. Some parents asked how they can purchase the device for their children who are hard of hearing, he added. However, Chen said it will take three to five more years to improve the system’s translation accuracy for commercialization.

Greg Markiewicz, a business development officer at the UCLA Technology Development Group, said the TDG helps bring research products like the ASL glove out of the lab and into the market.

Markiewicz said he hopes to apply Chen’s invention in settings where the technology will help people communicate more effectively. Once the device is ready for the commercial market, Markiewicz said he and the TDG will work with Chen to collaborate with companies for manufacturing and commercialization.

A potential commercial use for the glove, Markiewicz and Chen said, could be to help people learn sign language. Using the glove while learning sign language would give users immediate feedback while practicing their signing, Chen said.

Mark-Anthony Valentín, the president of Hands On at UCLA, a club that teaches students sign language and about the deaf community, said the tool has issues that other translation apps have.

Valentín, a second-year human biology and society student, said that American Sign Language has the same subtleties that any other spoken languages have, such as different dialects and unique cultural aspects. These subtleties mean that the glove has similar issues to how Google Translate and other translation apps have trouble distinguishing dialects in spoken languages.

“All languages are very human and very in the flesh,” Valentín said. “Especially ASL.”

Valentín, who is hard of hearing and has deaf parents, said he believes there are some potential applications for the glove, especially when the technology is even faster.

Chen said that when he was 6 years old, he had a friend who had trouble hearing. He found it difficult to communicate with his friend, he added, which led him to want to develop a cost-effective wearable technology to break down barriers to communication.

After learning that hundreds of thousands of people use American Sign Language in the United States, Chen said he put an emphasis on “sensing” technology while developing his lab at UCLA.

“I’ve always hoped that we would develop a low-cost and effective (tool) to translate sign language and promote communications throughout our society,” Chen said. “And when I started my research at UCLA, I knew it was a good time for me to do that.”