UCLA researchers find success with preventative therapy for bipolar disorder

(Farrah Au-Yeung/Daily Bruin)

By Priscilla Guerrero

Jan. 28, 2020 12:07 a.m.

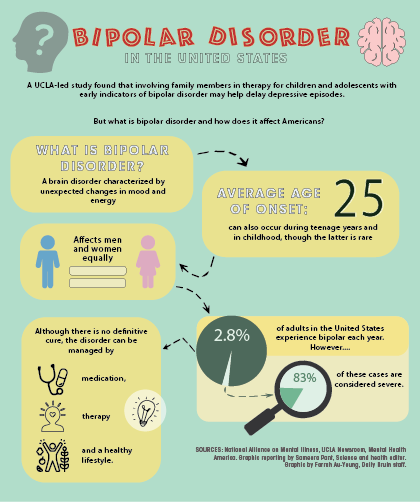

A UCLA-led study found that involving family members in therapy for children and adolescents with early indicators of bipolar disorder may help delay depressive episodes.

A team of researchers from UCLA, the University of Colorado and Stanford University studied 127 children and adolescents between the ages of 9 and 17 who showed early signs of bipolar disorder. Each patient was randomly assigned to one of two therapies: 12 sessions of family-focused therapy or six sessions of standard psychoeducation therapy, both over the course of four months.

Family-focused therapy helped the patients stay well for longer durations compared to standard treatment options, according to the study.

People with bipolar disorder experience extreme moods, said David Miklowitz, lead author of the study and professor of psychiatry at the Semel Institute for Neuroscience and Human Behavior. The moods change from high-energy manic episodes, characterized by being overly happy or excited with a sense of grandiosity, to low energy or depressive episodes, characterized by lack of energy, disinterest in daily activities and suicidal thoughts, Miklowitz said.

The children and adolescents involved in the study were at risk of developing bipolar disorder because they had a parent or grandparent with the disorder and showed symptoms such as depression, Miklowitz said.

During family-focused therapy sessions, clinicians teach the family more about bipolar disorder and help them form plans in the case of a relapse. Families learn to recognize when the child’s symptoms worsen and are taught ways to help by forming better communication and problem-solving skills, Miklowitz said.

“The therapist is kind of like a director, but the actual acting is done by the family,” Miklowitz said. “For example, when we teach them about listening, we don’t just say ‘Here’s what good listening is – nodding your head and keeping good eye contact.’ We actually have them do it in the session, so you speak and someone else in the family practices listening, and then we have them rehearse it.”

The psychoeducation therapy was a combination of three family meetings and three meetings with just the patient, focusing on identification of bipolar symptoms, talking about different treatments and developing a plan the family could use to handle future symptoms, said Aimee Sullivan, a co-author of the study and a psychologist at the University of Colorado Helen and Arthur E. Johnson Depression Center.

Though psychoeducation is beneficial because it educates the patient and parents about the disorder and available treatments, it does not change the factors that contribute to earlier onset or more severe symptoms, such as tension at home or the child feeling isolated, that make it difficult for the individual to respond or improve with treatments, said James McCracken, director of the division of child and adolescent psychiatry at the Semel Institute.

In the study, 77% of the children and adolescents in the family-focused therapy experienced a recurrence of a depressive episode after an average of 87 weeks, while 65% of the children and adolescents in the psychoeducation therapy experienced a recurrence after an average of 63 weeks, Miklowitz said.

“What this means is that we may be able to identify kids who are at risk of developing bipolar disorder early and give them a brief course of family therapy in 12 sessions,” Miklowitz said. “That may help them from having future episodes, or at least elongate the periods in which they’re well between episodes.”

The patients had the option to take medication alongside the therapy, but only about 60% chose to use medication, Miklowitz said. After the four months of treatments ended, the participants’ episodes were tracked over the course of one to four years, depending on when they entered the study and how long they continued in it, he added.

It is common in other fields of health for individuals with an elevated risk of developing conditions such as heart disease or diabetes to receive information to delay or prevent the onset of the illness later on, Sullivan said. However, she said this practice has not been embraced in other fields.

“But in the field of behavioral health, psychology and psychiatry, we’re just starting to look at this idea of preventative behavioral treatment for high-risk populations,” Sullivan said. “Given the strength of the impact of family-focused therapy on kids and adults who have bipolar disorder, we wanted to see if it would have this potential impact for high-risk kids in either delaying or preventing the onset of bipolar disorder.”

Sullivan said she works primarily with bipolar patients and teaches skills from family-focused therapy often. The skills taught in the family sessions are especially applicable to families that have high levels of conflict, she added.

Both UCLA researchers and the team at Colorado have been trying to increase access to their research to people not affiliated with the research study, Sullivan said. She said she is visiting clinics in Colorado to train other clinicians to use family-focused therapy.

This study is important because it is one of several that show how important a child’s environment and family is to their well-being, McCracken said.

“Even though they are children at high risk for developing bipolar disorder, which people often presume is completely determined by their genetics, this study shows so strongly that the child’s environment and their relationships with parents and their siblings are really important in determining their well-being and future,” McCracken said.