State stem cell agency grants 3 UCLA scientists total of over $18 million

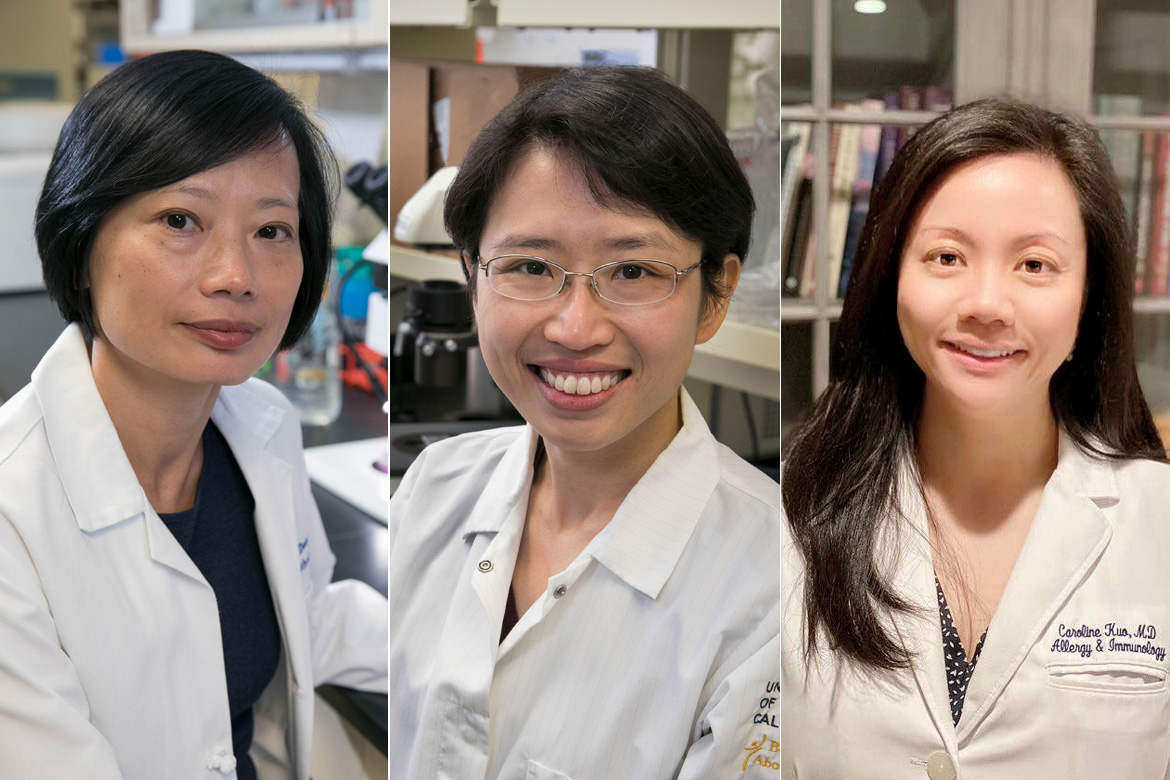

Sophie Deng (left), Yvonne Chen (center), and Caroline Kuo (right) collectively received over $18 million to develop clinical trials for personalized medical treatments. (Courtesy of UCLA Newsroom)

By Sarah Nelson

Nov. 25, 2019 12:51 a.m.

This post was updated Dec. 6 at 2:34 p.m.

Three UCLA researchers collectively received over $18 million to develop and conduct clinical trials for stem-cell-based treatments.

Sophie Deng, an ophthalmology professor; Yvonne Chen, an associate professor of microbiology, immunology and molecular genetics; and Caroline Kuo, an associate clinical professor of pediatrics, were awarded this funding by the California Institute for Regenerative Medicine, California’s stem cell agency.

Deng, Chen and Kuo are all affiliated with the Eli and Edythe Broad Center for Regenerative Medicine and Stem Cell Research at UCLA.

With the funding, Deng, Chen and Kuo hope to advance the field of personalized medicine through targeted genetic therapies in their respective specialties.

Deng received $10.3 million for a four-year clinical trial studying limbal stem cell deficiency. Limbal stem cell deficiency affects the cornea and causes blindness in the eye. Limbal stem cells are sourced from tissues surrounding the cornea and are responsible for continuously replenishing corneal cells.

Steven Peckman, the deputy director of the UCLA Broad Stem Cell Research Center, said what is groundbreaking about Deng’s research is the hope of creating vision in both eyes using stem cells after it has been lost. Processes which reestablish vision in one eye have already been approved in Europe, he added.

Limbal stem cells are necessary as the cornea, which is the clear protective outer layer of the eye that allows it to focus on objects, can lose cells because of day-to-day use, infection, surgery or prolonged use of contacts.

Corneal diseases are the fourth most common cause of blindness, with 25 million people affected worldwide. The most common means of regaining use of the eye in such cases is through corneal transplants. However, a recipient’s immune system may reject the transplant.

Research is currently expanding on the possibility of regaining eye function through reprogrammed limbal stem cells extracted from a patient’s existing store. After extraction, these cells are transplanted back into a patient’s eye, avoiding the hazard of recipient rejection.

Chen was granted $3.2 million to use over a two-year period. Her research works to advance tailored chimeric antigen receptor, or CAR, T-cell therapy in patients with multiple myeloma. Myeloma is a form of cancer which targets white blood cells that protect against disease. This type of cancer thus far only has short-term treatment options.

CARs are synthetic proteins engineered to be expressed on T-cells, which are white blood cells that are responsible for targeting and destroying pathogenic invaders, by exposing the cells to lentiviruses or crippled HIV viruses. In this way, they become CAR-T cells.

To direct CAR-T cell therapy in patients, Chen isolates T-cells from a patient’s blood sample and exposed the T-cells to lentiviruses encoded with the code for synthesized CARs. As a result, the T-cells can express CARs on their surfaces, helping to treat the patients.

An issue with CAR-T cell therapy is that tumors can escape detection from T-cells. As a result, tumors disappear and then become resistant to T-cells when they reappear. This is because T-cells are unable to recognize antigens, or proteins on the tumor’s surface, which are often lost after a tumor has disappeared. This is called antigen escape.

Current CAR-T cell therapy is monospecific, recognizing one antigen on myeloma cells. As a result, there is a higher risk that a tumor may not be detected. Additionally, not all myeloma cells have receptors for specific antigens, such as the CS1 marker. As the CS1 marker is present on 90% of myeloma cells, individuals with myeloma cells who do not have this marker are left highly susceptible to antigen escape.

A method of avoiding this is bispecific CARs, Chen said. Her iteration of CAR-T cell therapy is aimed toward generating T-cells that recognize both antigens: BCMA and CS1 markers. Chen said this would increase effective treatment in more individuals affected by myeloma.

“We believe that increasing the number of specificities from just BCMA to both BCMA and CS1 would increase the pool of patients who would actually be eligible, first of all, for the therapy, and secondly to reduce the probability of antigen escape (and relapse),” Chen said.

Kuo’s grant of $4.9 million will be spaced out over a duration of two-and-a-half years, she said. Kuo is studying X-linked hyper IgM syndrome, or XHIM, an immunodeficiency syndrome which results in multiorgan dysfunction and is nearly exclusive to men, according to the National Institutes of Health. The disease occurs in one of every 500,000 male newborns, the NIH states.

T-cells and B-cells are both white blood cells involved in the body’s immune response. T-cells identify pathogens that cause disease, while B-cells create antibodies to fight off these diseases.

T-cells and B-cells communicate by means of the CD40 ligand gene. XHIM patients lack this gene on their T-cells. Without CD40LG, pathogenic invaders cannot be marked for destruction, and the individual is at risk of infection and multiorgan dysfunction.

Kuo plans to edit a patient’s stem blood cells and insert the portion of genetic code which ensures the creation of CD40LG. This would enable the patient’s own cells to begin generating the gene. Following this, she said she plans to inject the corrected cells back into the patient, which will ensure the immune system’s continued health.

Current treatment options for XHIM lie in bone marrow transplants, matched with multiple rounds of chemotherapy, or monthly infusions of antibodies, Kuo said. However, infusions leave risk for infection, and many rounds of chemotherapy may endanger patients as they already have weakened immune systems.

The current rate of survival of XHIM patients is 30% of patients living until the age of 30. People with XHIM may suffer from associated multiple organ dysfunction and infections of the liver and lungs, such as cryptosporidium, which sometimes leads to cancer or liver failure, Kuo said.

Kuo has seven years of experience studying rare diseases, which led her to study XHIM, she said. Her research has also led her to work with the Hyper IgM Foundation, which was founded by an individual with a son born with XHIM. She hopes others will use her research in work on other disease therapies.

“We are trying to establish a kind of foundation or platform by which other people or groups can use this technique to develop curative therapies for other diseases,” Kuo said.