Lab studies estrogen receptors, bone density for potential osteoporosis treatment

By Qiaozhen Wu

Feb. 5, 2019 1:16 a.m.

UCLA researchers found silencing certain estrogen receptors in the brain dramatically increases bone density, offering a potential treatment for women with osteoporosis.

Stephanie Correa, an assistant professor of biology, started studying this treatment while she was a postdoctoral student at UC San Francisco. She said she noticed female mice gained weight when she genetically removed estrogen receptors in a region of the brain related to feeding and movement. She said she had expected the female mice to gain a substantial amount of weight in fat and lean muscle.

“It was significant, but it really wasn’t very much weight, so I looked at the change in fat – nothing. Then lean mass – nothing,” Correa said. “I just kept looking to explain this small effect, and we found this effect on the bone.”

Correa said the researchers’ immediate thought was that the increased bone density was caused by elevated estrogen levels in the blood that resulted from deleting some of the receptors. They used a technique called “conditional knockout” to delete estrogen receptors in two smaller regions of the hypothalamus to narrow down which receptor caused the bone density change.

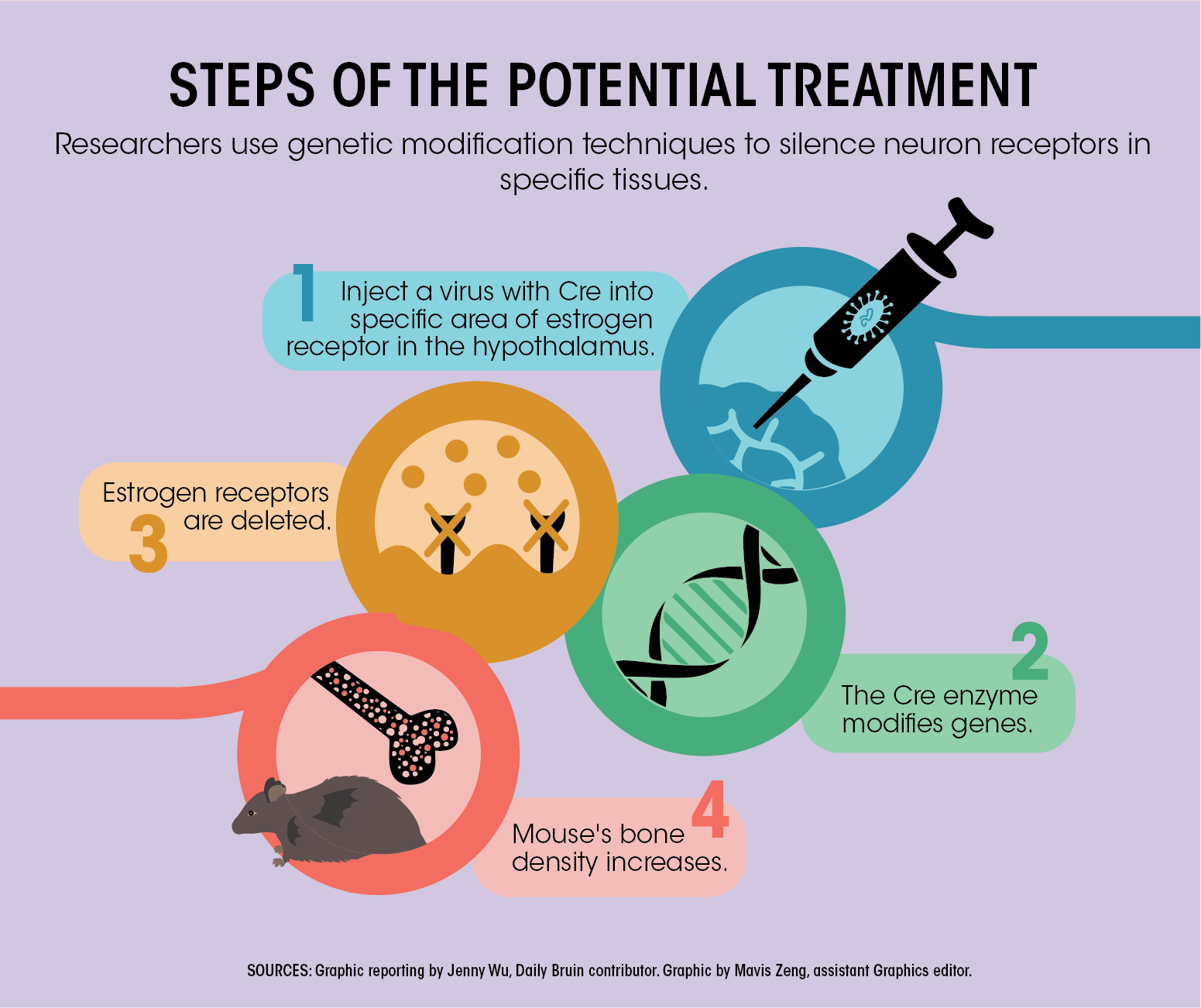

Conditional knockout is a technique that introduces Cre recombinase from Cre, an enzyme that modifies genes, to silence neuron receptors in specific tissues.

“We saw the effect again in one of the regions, but this mouse didn’t have elevated estrogen level in the blood,” Correa said. “We realized that this was not due to estrogen in the blood, this is something in the brain”

Correa injected a virus into the adult mice that carried Cre recombinase to the brain, allowing researchers to target more specific areas of the brain.

Zhi Zhang, a postdoctoral researcher at Correa’s lab and an author of the paper, said the researchers tested other tissues that may have been potentially silenced by the knockout, which made sure that the effect came from the brain.

Holly Ingraham, a professor in the Department of Cellular and Molecular Pharmacology at UC San Francisco and senior writer of the article, said she was surprised to find that neurons in the brain can affect bone density. However, she added researchers still know little about the mechanism behind this regulation, and why it only affects females.

“My lab is researching who and how the estrogen receptor in the brain talk to, whether it is through hormone or neuron pathways and what is the activity in the bone,” Ingraham added.

The study also highlights the importance of studying both sexes in medical research, Correa added.

“It’s possible that the result is surprising, because for a long time, people haven’t studied females,” Correa said.

Correa said the research could provide a new way to think about the side effects of drugs that affect estrogen production. Many women take drugs to balance estrogen and progesterone hormone levels during menopause. Breast cancer patients also take medications that slow the production of estrogen.

“All of these estrogen-sensitive neurons are going to be affected,” Correa said. “There would be potential effects on bone and body weight that we need to understand more about”