Study finds connection between effects of exercise, levels of particular protein

By Joseph Ong

Jan. 17, 2019 1:39 a.m.

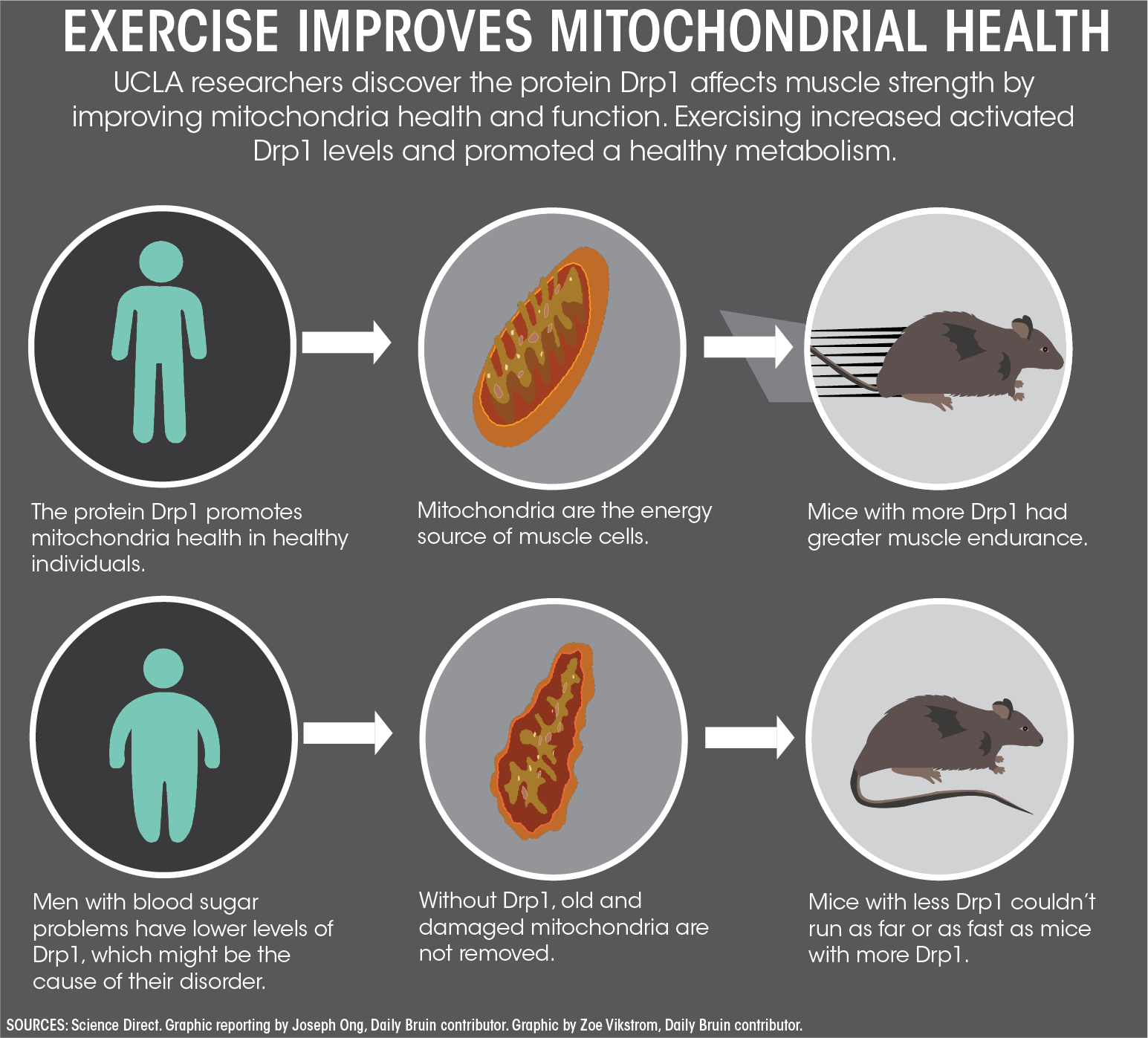

UCLA researchers uncovered a link between mitochondrial health and exercise, offering a new explanation for the causes of some metabolic disorders.

In a study published in December, UCLA researchers in the lab of Andrea Hevener, a professor of medicine, characterized how mitochondria change in response to both short- and long-term exercise. Researchers found that mitochondrial health is mediated by the protein Drp1, which is deficient in some men with metabolic disorders. The study is the first to track changes in mitochondrial health over time in response to exercise.

Mitochondria are structures within a cell that convert food into energy that cells can use. They play an important role in exercise and cell health, but no study has looked at the relationship between exercise and mitochondrial health, said Timothy Moore, a University of Southern California graduate student who works in Hevener’s lab.

The researchers began by exercising mice for 90 minutes on a treadmill and comparing the muscles of exercised mice to those of sedentary mice. They found that mice who exercised developed an increase in the expression of genes involved in forming new mitochondria and destroying old and broken mitochondria.

Moore said one protein in particular, Drp1, stood out because its RNA levels increased immediately after exercise but decreased afterward. Drp1 is a protein involved in mitochondrial fission, the process by which one mitochondrion divides into two, said Whitaker Cohn, a co-author of the study and graduate student at UCLA.

This rise and dip in Drp1 RNA levels suggests that mitochondria fusion and fission play an important role in the body’s response to exercise, said Lorraine Turcotte, a professor of biological sciences at USC and a collaborator on the study. She said she thinks Drp1 RNA levels increase immediately in response to exercise in order to pinch off and destroy old mitochondria.

“Mitochondrial fission is important for your ability to exercise,” Turcotte said. “First, you have to clean up the mitochondria that aren’t so good.”

To study the importance of Drp1, the researchers genetically engineered mice to have less Drp1. Even though the Drp1-deficient mice weighed the same as normal mice and had the same amount of muscle, Drp1-deficient mice had more difficulty exercising, Moore said.

“(Drp1-deficient mice) are pretty fine under normal conditions, but if you exercised them, they didn’t perform as well as a normal mouse,” he said.

Drp1-deficient mice had lower maximum running speeds and ran shorter distances compared to normal mice, according to the study.

They also did not benefit as much from exercise as normal mice. While both normal and Drp1-deficient mice developed increased muscle endurance after a 30-day exercise regimen, the Drp1-deficient mice developed a smaller increase in muscle endurance than normal mice.

The muscles of Drp1-deficient mice also showed increased levels of stress, Moore said. He added that these results led him to believe that Drp1 mediates the health benefits of exercise and that mitochondrial health changes rapidly in response to both short- and long-term exercise.

To test how these results applied to humans, the researchers looked at dysglycemic men, men with higher or lower levels of blood sugar than average, and normoglycemic men, or men with average blood sugar. The researchers found that the dysglycemic men had lower overall levels of Drp1 RNA.

This lack of Drp1 may be a cause of their metabolic disorders, Turcotte said. She added without enough Drp1, the dysglycemic men may have never cleared the unhealthy mitochondria within their muscle cells, contributing to their poorer metabolic condition.

Moore said he is expanding his research to see how mice from various genetic backgrounds respond to exercise. He said his future work will try to answer why people respond differently to exercise and how genetic backgrounds cause some to benefit more from exercise than others.

“(We want to understand why) you and I can exercise the same amount, but we’ll have different results,” Moore said.