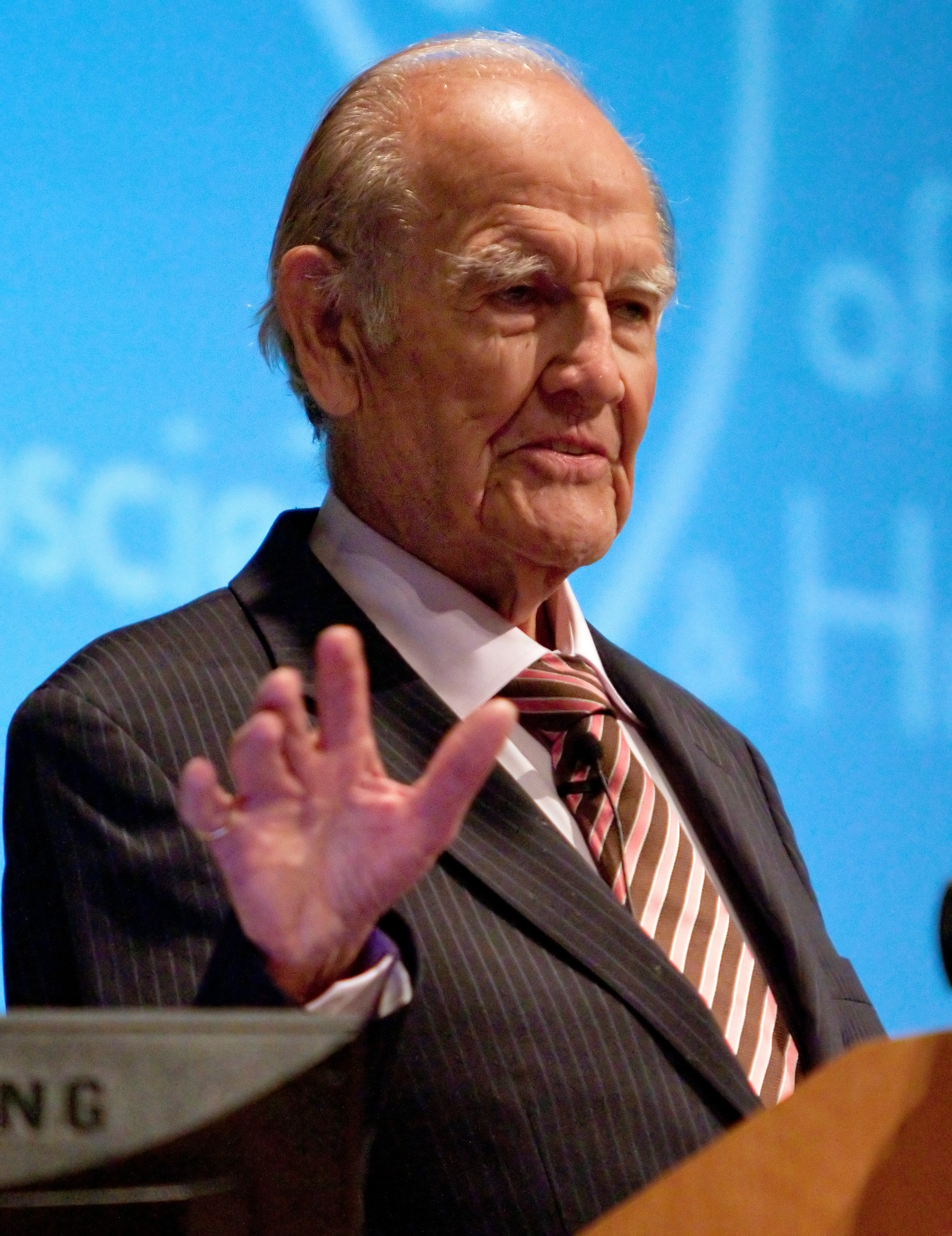

Former senator George McGovern speaks about mental illness at Open Mind lecture

George McGovern discusses his

family experience with mental illness.

By Golmah Zarinkhou

Oct. 8, 2010 12:42 a.m.

His front door loomed before him on a chilly winter night in 1994, as former senator George McGovern walked curiously forward and noticed the outline of a police officer and a priest waiting just outside.

He opened the door to learn that his daughter Terry, or “Ter’ the Bear” as McGovern called her, recently froze to death in the snow while heavily intoxicated.

“Losing a presidential race was tough, but losing a daughter was tougher,” McGovern said in a lecture Wednesday night at the UCLA Anderson School of Management.

He discussed the politics of mental health and spoke about his 1996 book “Terry: My Daughter’s Life-and-Death Struggle with Alcoholism” before a book signing as part of the annual Open Mind Lecture and Film series.

The lecture was sponsored by The Friends of the Semel Institute for Neuroscience and Human Behavior, a UCLA volunteer group dedicated to educating people about mental illness to help reduce the associated stigma, said Vicky Goodman, founder and president.

In a striped tie and brown loafers, McGovern addressed about 300 people, many clutching purple-covered copies of his book. The audience consisted of UCLA mental health professionals, marriage and family counselors, people touched by mental illness and others from West L.A., Goodman said.

McGovern said his favorite part of the lecture was talking about Terry, even though it is still difficult to think and speak of her.

Andrew Leuchter, psychiatry and biobehavioral sciences professor and faculty adviser to The Friends of the Semel Institute, also spoke to the audience about the effects of and relationship between depression and alcoholism.

“McGovern’s warmth and humor came through,” Leuchter said after the lecture. “It’s only through people such as him who speak about their own family history of mental illness that we’re going to succeed in destigmatizing these disorders.”

Both speakers answered questions from the crowd before McGovern signed books.

Among the sea of adults waiting for a signature, high school student Lucas Kouyoumdjian stood in line beside his mother.

He said McGovern’s lecture was inspiring because diabetes and his childhood asthma restricted some of his choices in life and showed him how swiftly illnesses such as depression can overtake the body.

“I was interested (in the event) because I have diabetes, and I’ve been exposed to other conditions that could strike you at a snap of your fingers,” he said.

In McGovern’s case, mental health became a political issue in the midst of his campaign for presidency against Richard Nixon in 1972. Termed the Eagleton Affair, the disclosure of McGovern’s running mate’s history of clinical depression caused his entire finance committee to resign and turned the majority of the country in Nixon’s favor, McGovern said.

Yet despite the stigma, he said people can function at a high level regardless of mental health struggles. He noted that former President Abraham Lincoln stopped carrying a knife in fear that he might slit his own throat in a fit of melancholy, a term for depression before it was better understood. And former British Prime Minister Winston Churchill medicated his depression with a quart of liquor per day, McGovern said.

“I want people to realize that (clinical depression) is a widespread affliction in the U.S.,” he said. “I’d like to think that 40 years later we’re a little more open with things like this.”