UCLA medical centers prepare for End of Life Option Act

By Lindsay Weinberg

May 31, 2016 12:36 a.m.

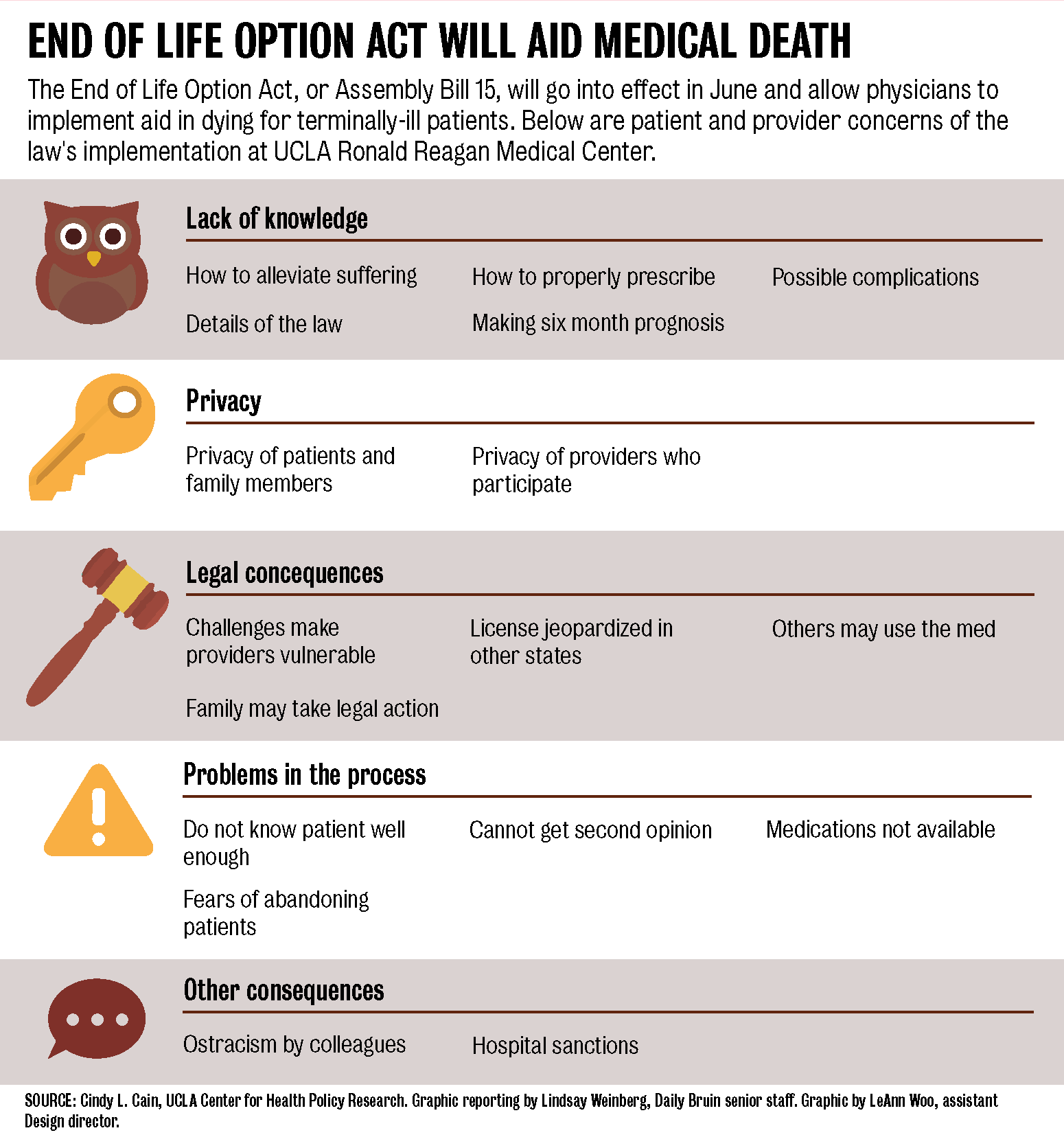

UCLA medical centers are training physicians and developing patient advocacy groups to prepare for an aid-in-dying law, which will go into effect June 9.

The End of Life Option Act will permit doctors in California to prescribe self-administered, life-ending medication to patients who are terminally diagnosed to live for six months or fewer. To receive the medication, patients must make two oral requests for the prescription 15 days apart and pass a mental health evaluation if there are indications of a mental disorder, among other qualifications.

Though the University of California will implement the law, individual health care providers can opt out of prescribing medications, said David Wallenstein, a physician in the UCLA Palliative Care Service.

The legislation includes a series of requirements to protect patients against coercion, such as requiring witnesses to sign the medication request, said Cindy Cain, an assistant professor-in-residence at the UCLA Fielding School of Public Health. Patients, not physicians, bear the burden of asking about the aid-in-dying option, she said.

“If the general public understood that the law is really written to protect against vulnerabilities and to provide additional options to them, I think that would be a good step,” Cain said.

Neil Wenger, director of the UCLA Healthcare Ethics Center and professor of medicine, formed a 45-person advisory committee to give recommendations about how to implement the law. The work group, which includes physicians, nurses, social workers, clergy and administration, advised administrators on specific policies and guidelines for the End of Life Option Act at UCLA.

During committee discussions, some members said they believed it’s inappropriate for physicians to be involved in a patient’s end-of-life decision, while others strongly supported it, Wallenstein said. The goal of the discussion was to consider what is best for patients and health care providers who may feel uncomfortable prescribing the medication, he said.

Wenger and other committee members have begun training physicians in small groups, he said. Training will include an educational session during some weekly departmental meetings, he said.

“Physicians are trained to save lives and so this is not always a part of what they’re the most comfortable with,” said JoAnn Damron-Rodriguez, adjunct professor at the UCLA Luskin School of Public Affairs.

Cain said she thinks an interdisciplinary conversation with social workers and health care providers would help physicians learn how to interact with patients facing difficult decisions.

“It needs to be more than just one person’s decision – it should be something that’s discussed in a wider group,” Cain said. “I think we’d be able to improve care overall rather than just leaving it in the hands of physicians.”

Wenger said the work group decided to develop an extra layer of patient protection: a patient advocacy group consisting of psychologists and social workers who are trained to work and bond with dying patients.

Cain said she thinks patients don’t typically understand the requirements or when aid in dying can be an option. She added they base their knowledge on high profile cases such as with Brittany Maynard, a young woman with brain cancer who moved from California to Oregon to die. In 1997, Oregon passed the Death with Dignity Act, the first state to allow physician aid in dying.

“I have patients contact me and they think that they can sort of come in and say, ‘Alright I’m ready to go,’ and that it’s something which happens instantaneously,” Wallenstein said. “Obviously that’s not the case.”

According to the End of Life Option Act, patients must be residents of California, which Damron-Rodriguez said prevents the creation of a tourism industry for people coming to die.

Though the legislation operates under the premise that patients self-administer the medication, some people are concerned family members may administer the dosage if patients become physically unable to take it themselves, Damron-Rodriguez said.

Damon-Rodriquez added she thinks aid in dying will not become a common practice because of the qualification process laid out in the legislation.

Fewer than 100 people per year died using such medications in Oregon until 2014, according to a health policy brief Cain wrote about other states’ aid-in-dying laws. People are comforted by the option of aid in dying, even if they do not ingest the medication, according to the research.

Wallenstein said a small number of patients in other states request assistance in dying, and an even smaller number actually ingest the dosage. Therefore, he does not think the End of Life Option Act will affect his practice.

The law will spark conversations with his patients about their options toward the end of life, including treatment, Wallenstein said.

“Not a week has gone by without a serious new terminally ill patient asking me about how they can end their lives,” Wallenstein said. “(The law) will empower patients to be (more frank) with me so we can talk more freely about their goals and symptoms that are really troubling them.”