Abhishek Shetty: Ending the embargo in Cuba ineffective until end of regime

(Kelly Brennan/Daily Bruin senior staff)

By Abhishek Shetty

March 31, 2016 12:00 a.m.

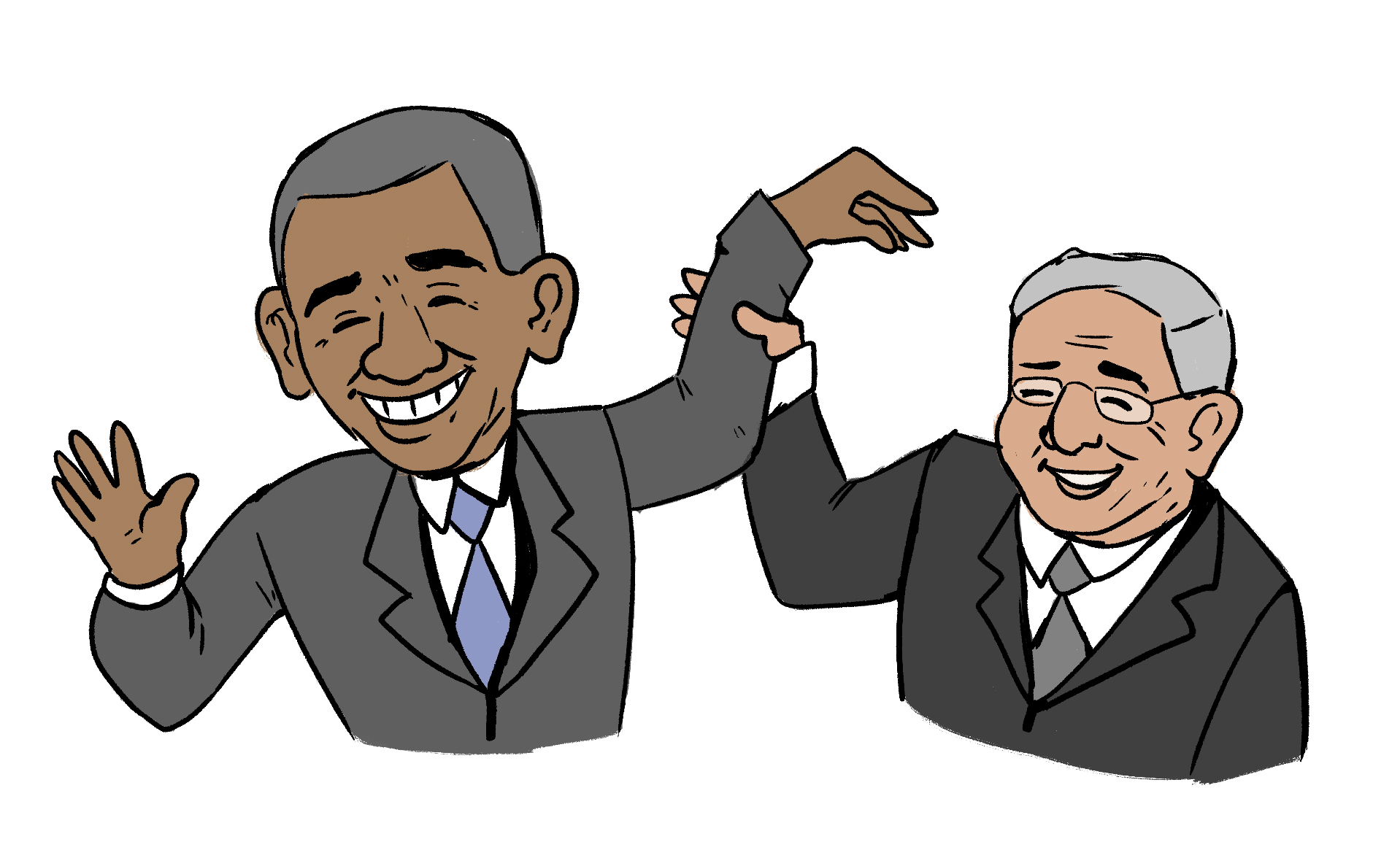

Any chances of the Cuban people benefiting from the current course of the U.S.-Cuba thaw appear limper than President Barack Obama’s hand propped up by a gleeful Raul Castro.

In his 2015 State of the Union Address, Obama resolutely declared, “When what you’re doing doesn’t work for 50 years, it’s time to try something new.” Although this may sound like a statement he should have considered before pursuing his current Middle Eastern policy, this was his view on American-Cuban relations.

Following up on his statement, Obama has gradually eased the embargo on Cuba. The embargo was first imposed in 1962, when President John F. Kennedy broadened existing trade restrictions following Fidel Castro’s takeover of Cuba in 1959 and the United States’ failed Bay of Pigs invasion in 1961. Cuba lost more than a trillion dollars in trade with the U.S., and its economy was further crippled by the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991. A famine followed in the immediate period, exacerbating poverty and homelessness across Cuba. Currently, the average Cuban makes 22 U.S. dollars a month, and crumbling infrastructure paints a morose picture of urban Cuba. Looking at the “new” course of action that has followed in Cuba, it is unlikely a substantially improved Cuba is imminent. For a definitive change in Cuban citizens’ conditions, Obama will have to push for at least a few democratic concessions in Cuba

Pressing for democratic measures in other countries is territory the U.S. has approached before. The U.S. lifted its embargo on Vietnam following its agreement to assist in accounting for missing in action soldiers from the Vietnam War. Congress passed the Comprehensive Anti-Apartheid Act of 1986, and repealed it only when South Africa met the United States’ conditions. The U.S. also pressured Philippines leader Ferdinand Marcos to hold democratic elections in 1986, and even denounced the results of the election on account of electoral fraud. In the case of Cuba, Obama has made suggestions of giving people the power to express themselves and has expressed support for democracy, but no concrete measures have been mentioned.

The fight for democracy in Cuba is led by dissidents, who met with Obama on March 22. Antonio Rodiles, one of the dissidents, had said in 2014 that normalization of U.S.-Cuba relations would result in more severe crackdowns on dissidents. Two days before the visit he had been arrested by police, who broke one of his fingers. At the meeting with the dissidents, Obama reiterated his support for Cuban democracy and free speech. The meaninglessness of the statement of support was underlined when Rodiles was arrested and bruised up again five days after.

If there were any hopes that the thawing of relations might help privatization, free market economics and economic freedom thrive in Cuba, Deborah Rivas, head of foreign investment at the Cuban Ministry of External Trade and Foreign Investment, dispelled them. Speaking to Cuban Communist Party daily Granma, she said, “The goal is not to sell the country, it’s not about doing just any project that interests some foreign investor. It’s a matter of attracting investors whose projects coincide with our public policy.” Cuba will continue to incrementally approve projects and foreign direct investments that it sees as beneficial to the government, rather than the people.

Even the incremental arrival of American businesses has its own problems. To make room for tourists, Cuban company Habaguanex has been renovating buildings in tourist zones, displacing residents into distant suburban areas. This gentrification of residents for incoming tourists will create urban sprawl and its associated problems, such as longer travel times and inefficient transport systems. Executives from Starwood Hotels and Resorts traveled with Obama and made a deal to take over three state-run hotels. Cuba, with its tourism industry, is ripe territory for U.S. businesses to further take over buildings centrally located in cities.

Apart from tourism, agriculture also supports Cuba’s languishing economy, employing 20 percent of the workforce. With the U.S. agricultural industry looking to expand into Cuba, more productive American farmers could easily flood the Cuban market with cheaper commodities. Similar to the plight of Mexican farmers following the signing of the North American Free Trade Agreement, a number of Cuban farmers, unable to compete against industrialized American agriculture, would have to give up farming altogether.

The U.S. had followed a policy of isolation with Haiti in the early 19th century, before capturing it in 1915 and later intervening again following a blockade between 1991 and 1994. Even with aid being provided, Haiti is one of the most corrupt countries in the world and has a poor human rights record. Similar to Cuba, the U.S. has reiterated its support for democracy in Haiti, but the results are dismal. This set of events underlines that U.S. influence without a hard-line on social and political freedom and human rights will barely benefit the Cuban people.

This isn’t to say that Cubans are better off without a thaw in U.S. relations. Poverty, homelessness, food insecurity and crumbling infrastructure are entrenched in Cuban society. However, the current course of thawing relations without decisively pushing for democratic measures will barely help the Cuban people. Foreign investment and tourism will add to the Cuban economy, but under Castro’s regime it is unlikely the average Cuban will see substantial improvements in living standards.

People will start to benefit from

foreign investment only when economic and social freedom is guaranteed in Cuba,

instead of being left at the mercy of trickle-down economics from the tourism

industry and a repressive communist government.