Professor bonds biochemistry and the humanities together in class

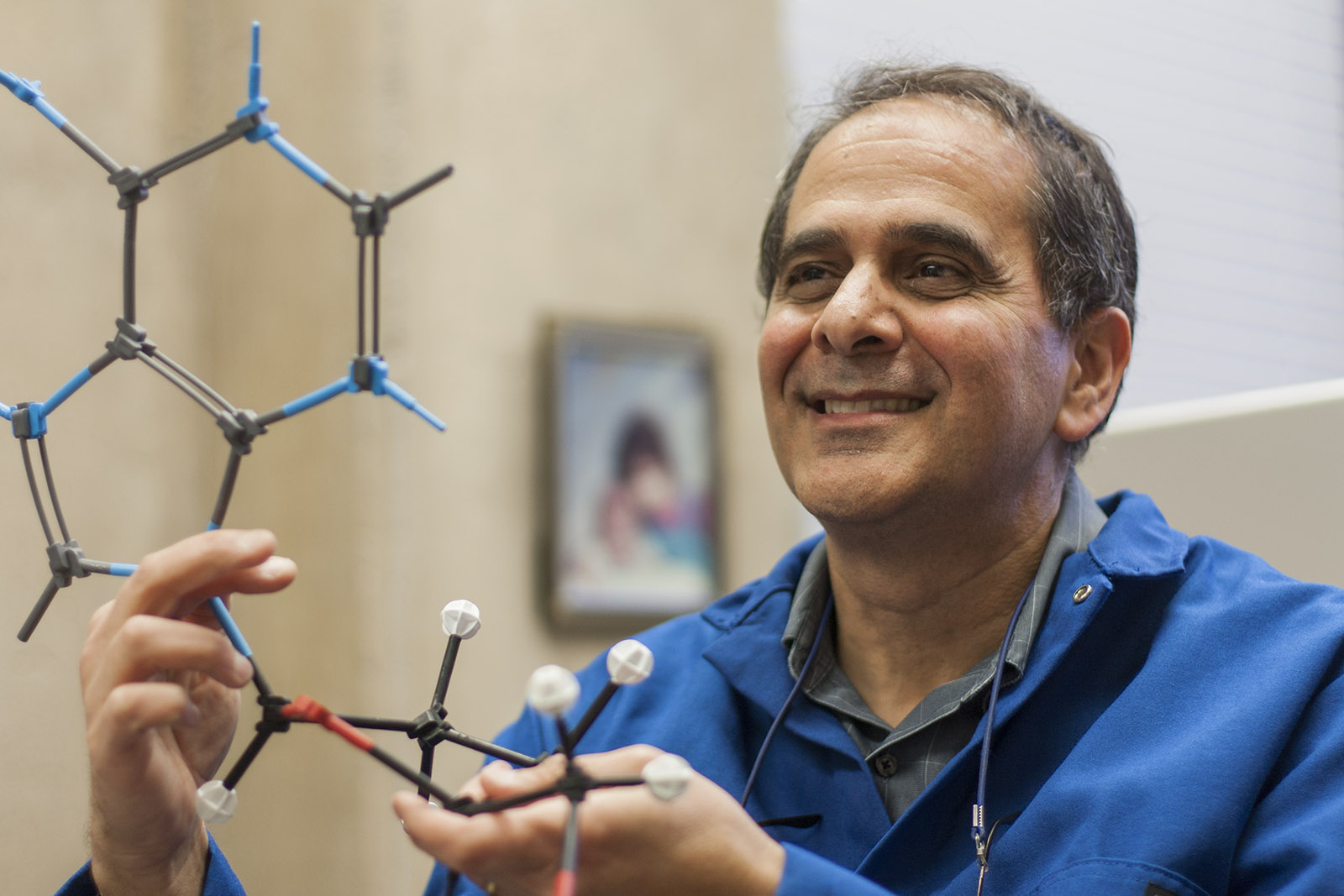

UCLA biochemistry professor Albert Courey’s passion for poetry stems from his childhood fascination with music and the arts. (Kathy Chen/Daily Bruin)

By Kun Yong (Sean) Lee

Feb. 2, 2016 7:30 a.m.

About 10 years ago biochemistry professor Albert Courey put on sunglasses and a backwards hat and rapped “The Rhyme of the Ribozyme,” a verse written by Dennis Kuo, an alumnus who took Courey’s class on DNA and RNA biochemistry.

“If the students have to think about how to express a scientific fact in an artistic way, it makes them think about it in a different way,” Courey said.

Courey’s teaching style bridges UCLA’s academically segregated North and South campuses. His biochemistry students learn about DNA supercoiling and gene translocation with a touch of his original iambic pentameter poetry and some hip-hop brought on by the “Rhyme of the Ribozyme.”

His dual identity as both a scientist and a dabbler in the humanities stems from his childhood allure to both fields.

When Courey was 7 years old, his father bought a baby grand piano to use as a living room decoration, but eventually decided his two sons would receive piano lessons.

While his older brother lost interest, Courey heard beauty in Prokofiev and Beethoven’s compositions. He expanded his musical endeavors by playing trumpet in his elementary school orchestra and being an active member in his high school’s band program.

Along with providing Courey’s first piano, his father was also a physician who instilled in Courey a fascination for science that paralleled his early dedication to music.

“I loved music,” Courey said. “But I was also fascinated by developmental biology, (like) how a fertilized egg turns into a complex animal.”

However, Courey found that his two passions contained a unifying factor. His research on the structure and functions of DNA and his studies in music both concerned disparate processes that come together and cause change.

“When you’re looking at a piece of music you have to be analytical,” Courey said. “You have to look at its structure, how parts fit together and how themes evolve.”

Courey attended Oberlin College in 1975 and decided to study both fields, hoping to major in biology and piano performance. He soon found himself balancing the pieces of Frederic Chopin with lab experiments, rushing from the practice rooms where he was rehearsing for his senior recital to the biology labs where he was conducting research for his senior thesis.

Oberlin was also where Courey met his wife, Jody Reichel, who was an English student. During freshman orientation, she asked him to accompany her singing while practicing for a musical audition.

“He is a wonderful accompanist,” Reichel said. “We sing songs ranging from George Gershwin standards to Schubert’s lieder, and it’s really fun for me.”

After Courey earned his doctorate in biochemistry from Harvard University in 1986, music took a backseat to his scientific aspirations. He continued his research at UC Berkeley and then moved on to teaching at UCLA, but the discipline he gained studying the arts manifested itself in a new way: poetry in the classroom.

Students in Courey’s biochemistry 153B class will be read original poems written in iambic pentameter such as “I Am Ribozyme, Hear Me Roar” or “Sonnet 1,” which begins with the line “Rifampicin, Rifampicin my shield.” Later in the quarter, students are given an extra credit assignment that asks them to do the same.

The assignment has become one of the more memorable moments for those who have taken the course.

Wiam Turki-Judeh, a former graduate student who received her doctorate in biochemistry from UCLA in 2011 and was Courey’s teaching assistant in 2006, remembers watching students recite their poetry and being amused by how science translated into art.

“It was so funny,” Turki-Judeh said. “(Courey) allowed students to think outside of the box which is something not many science professors usually strive for.”

At the end of the day, Professor Courey’s teaching creates a bond between creativity and logic that seamlessly blends them together, similar to the bonds in DNA structures.

“I think that science and the humanities exist synergistically,” Courey said. “They benefit one another in a way that allows students to see things differently.”