Q&A: Composer Patrick Gleeson talks film-scoring, ‘Crossroads’ legacy

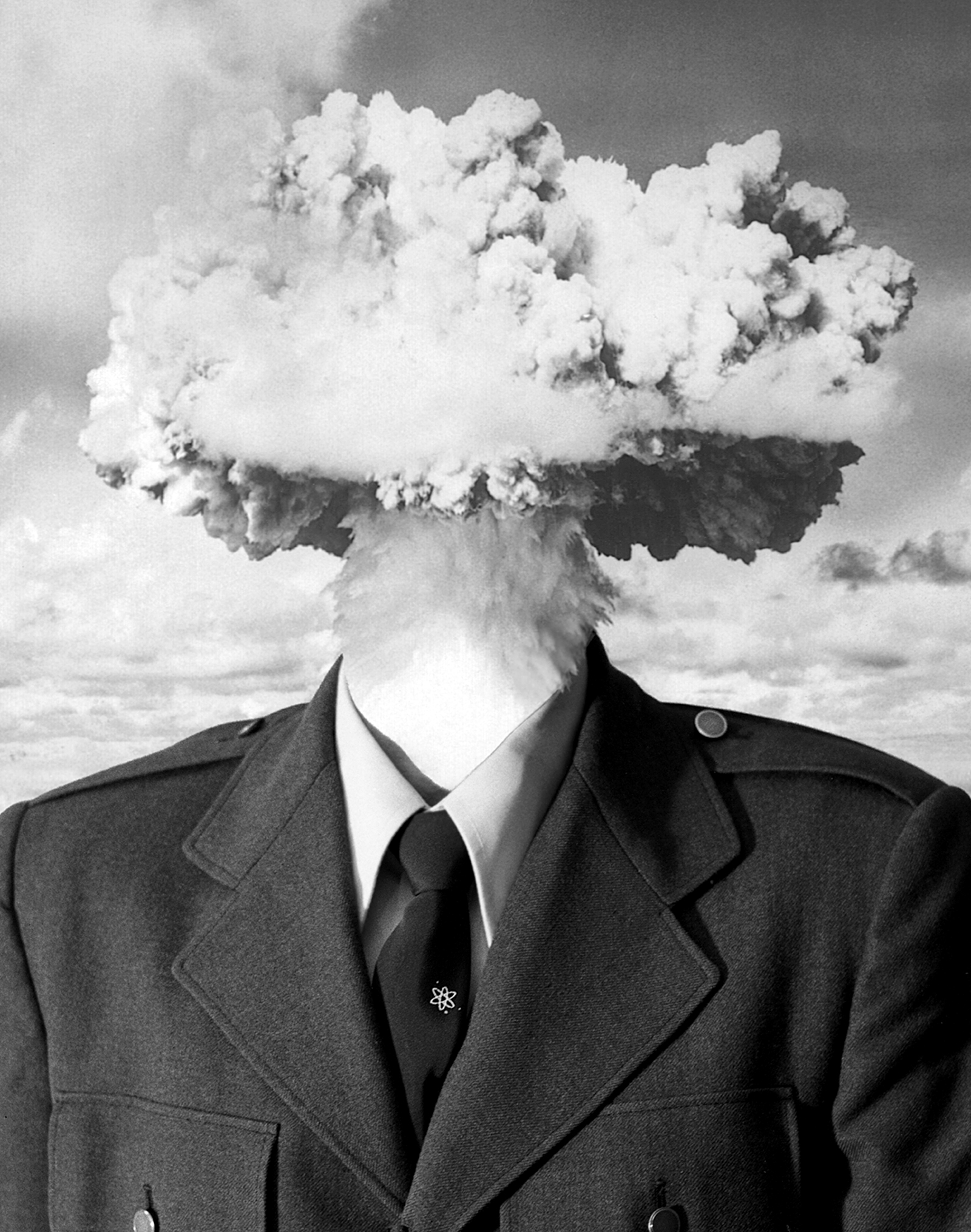

“Crossroads,” a 1976 film directed by Bruce Conner, utilizes footage of nuclear tests at Bikini Atoll. The film, scored by Patrick Gleeson and Terry Riley, will be screened Tuesday at the James Bridges Theater as part of Melnitz Movies.

(Magnolia Editions)

By Ian Colvin

Nov. 18, 2014 1:25 a.m.

The original version of the infobox accompanying this article contained an error. See the bottom of the article for more information.

Bohemian artists and beatniks flocked to San Francisco in droves during the 1950s and 1960s. At the height of this wave of migration, legendary avant-garde filmmaker Bruce Conner made the city his home and began creating filmic assemblages that juxtaposed snippets of archived footage set to music.

Tuesday at 7:30 p.m., Melnitz Movies will present a 35 mm print of Conner’s 1976 work “Crossroads,” a film that uses footage of nuclear tests at Bikini Atoll and music by composers Patrick Gleeson and Terry Riley. It is often considered to be one of the canonical productions of 20th-century experimental filmmaking.

The Daily Bruin’s Ian Colvin spoke with Gleeson, a pioneer of synthesizer music, about “Crossroads” and his involvement in West Coast avant-garde cinema.

(Museum of Modern Art)

Daily Bruin: You composed music for several films by Bruce Conner in the ’60s and ’70s. What were the circumstances that led to your initial collaboration?

Patrick Gleeson: One day, I took it into my head that I would put on a “happening.” I had no credits, no credibility, nothing. I went down to the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art and told the museum director, “I want to do this.” And he just responded with, “Well, when do you want to do this?” That was much the spirit of the era. In the ’60s, nobody knew what they were doing. We were all just having fun and being creative. It was a wonderful time for art.

Anyway, I went there, recited some poems I had written and presented some electronic music. One of the guys that was working on the lights for the show was Bruce. By the end of the evening, he and I hit it off in some weird way.

DB: And from there he asked you to record music for his films?

PG: Well, shortly after that experience I quit my job teaching and Bruce shows up at the door of this commune I’m living at and, in his high-pitched voice, says “Pat, I hear you quit teaching and you’re going to focus on music full time.” So the man starts coming over to my place from time to time just to listen to me improvise on the synthesizer. Finally, he ended up asking me to make a soundtrack for him, and that’s how our working relationship really began.

DB: What was the process like for making an avant-garde film such as “Crossroads” at that time?

PG: Each one was very different. With “Crossroads,” Bruce had finagled the Department of Defense into releasing actual Army footage of the atomic bomb tests in the Pacific. Why they were crazy enough to let him do that – I don’t know. So Bruce then compiled all this footage and then approached Terry Riley and me to work together to compose the soundtrack.

DB: How did the two of you work together when creating the film’s music?

PG: It became very clear as we worked in my studio – Different Fur – that there was tension due to artistic differences. The solution was to have Terry and me do two separate soundtracks, one for each half of the film.

But it turned out perfectly. Really the subject of the film is not a judgment of nuclear bombs, surprisingly. Instead, it just recognizes that (they are) an incredibly powerful force, like an Indian deity of destruction. So the first part of the movie is about the horrifying and appalling force of the atomic bomb, which is what I scored, while Terry, as a student of Indian religions, composed the music for the second half, which is about death and the Indian mythology of the peace that passes understanding.

DB: You have made music for a variety of different films, from Conner’s experimental movies to more mainstream Hollywood productions, such as Francis Ford Coppola’s “Apocalypse Now.” Have you found that avant-garde filmmaking provided you more creative independence, or did both modes of production give you the kind of artistic freedom you desired?

PG: It depends. My experience with Francis on “Apocalypse Now” was not very different from my experiences with Bruce. They are both very talented, very eccentric people, with a very strong artistic vision. When I came on board for “Apocalypse Now,” Francis really believed in what I was doing and made me the head of the project, permitting me a lot of freedom too. With both of them it was just like, “It’s up to you, brother.”

I’ve learned that the more qualified and talented people are, the more they leave you alone.

Compiled by Ian Colvin, A&E; contributor.

Correction: The info box contained information for the wrong event.