Report reveals gender inequity in UCLA School of Management faculty

UCLA Anderson School of Management still ranks last among 20 other competitive business schools for percentage of women faculty.

Women faculty at the UCLA Anderson School of Management consistently experience an inhospitable work environment and fewer career advancement opportunities than their male peers, several university reports reveal.

In a University of California Academic Senate report obtained by the Daily Bruin that was conducted during the 2013 fall quarter, reviewers identified the school’s current climate for women faculty as one of the primary challenges facing the business school.

Another internal report reviewing gender inequity at the school back in 2006 likewise identified several problems for women faculty, such as negative student behavior and gendered differences in promotional decisions, and outlined steps to address it.

Eight years later, however, the same issues remain, and many female professors at the school say the reports continue to reflect reality.

A flawed system

The recent Academic Senate report, which found a troubling work environment for women at Anderson, was based on a three-day site visit in October by four UCLA reviewers and three external reviewers.

“Men and women faculty start off at the school with more or less same levels of satisfaction,” the report says. “But at some point after their arrival, many women have the sense that perceptions have been formed, both consciously and unconsciously, that are unfairly negative.”

Female faculty often feel a lack of career advancement opportunities and a perceived lack of respect by peers.

One issue is some male students challenging the authority of female professors in disruptive ways.

The school’s reliance on student evaluations in the performance review process amplifies this particular issue. When the students who challenge the professors’ authority in the classroom then become responsible for evaluating them, it can sometimes hinder career advancement for female professors.

One female professor at Anderson, a tenured faculty member who asked to remain anonymous, said she has noticed that student evaluations are used in promotional decisions as the primary evidence of teaching quality. On average, female professors receive lower scores than their male counterparts – leading to a perceived gender bias, she added.

“Male faculty are assumed to be better than they look on paper and female faculty are assumed to be worse off than they look on paper,” the professor said. “That leads to a different level of scrutiny and skepticism about female versus male research records.”

Another female professor who asked to remain anonymous said she has observed this deeper scrutiny at various meetings and evaluation proceedings, where men are given the “benefit of the doubt” while females’ records are inspected more harshly.

Barbara Lawrence, who has taught at Anderson for more than three decades and served on the school’s gender equity committee during the 2006 study, agreed that faculty evaluation is one of the most flawed, systemic problems.

John Hughes, an accounting professor at Anderson, said he does not perceive a high level of bias or discrimination against women at the school.

He added that though the teaching experience may be more difficult for women faculty, he does not think this alone should lead to a complete overhaul of the existing performance review system.

“I take exception to sort of nominal or cosmetic efforts to modify current conditions,” Hughes said. “To me, you have to drill down to a very basic level to really have a meaningful address to the issues that are associated with diversity.”

The Academic Senate report states that merit advancement, promotion and salary are “primary ways an institution communicates how it values its faculty” and that for women at Anderson, “standards are unevenly applied” for these opportunities.

For example, remarks such as “he’s a good guy” sometimes stand alone when recommending male peers, whereas more substantive arguments are required for women, according to the report.

One female professor at Anderson who asked to remain anonymous said she deals with undermining comments “all the time.” She said these comments occur in one-on-one conversations, public meetings and faculty meetings on a regular basis.

“I don’t think there’s a conscious awareness that the comments are gendered. … There’s just an incredible lack of sensitivity of how some statements or behaviors contribute to the climate where women feel they have to perform at a much higher level to have the same opportunities as their male peers,” she said. “It’s a climate in which it’s accepted behavior such that males aren’t even aware.”

She added that mothers in particular can experience certain challenges.

The same actions taken by male and female faculty are also viewed differently.

According to some female faculty, if a male professor co-authors an article with his students, many see it as evidence of good mentorship. However, when a female professor does the same, many see it as her students doing work for her.

In recent years, the Anderson school has made several negative recommendations regarding promoting a female faculty member, which were later overturned by the Committee on Academic Personnel and the Executive Vice Chancellor, according to the report. Reviewers said they are not aware of any such cases involving male faculty members despite their larger presence at the school.

Kimberly Freeman, the assistant dean for diversity initiatives and community relations at Anderson, said she has not personally seen evidence of an inhospitable work environment for female faculty, but she thinks more must be done to improve the school’s campus climate.

She added that she cannot comment on individual cases or the frequency of occurrences such as negative recommendations that were overturned.

Though the prestige is high, Lawrence, who is the second female professor in Anderson’s history to receive tenure, said she has not been entirely happy at Anderson. While acting as a visiting faculty at another major university years ago, she rediscovered her love of teaching.

“I realized while I was there how much stress I’d been under,” Lawrence said. “It really taught me something. … It’s not healthy.”

Combined factors of negative peer perceptions, undermining comments, a “distrust of the way the school handles personnel actions” and lower student evaluation scores often dissuade women faculty from putting themselves up for promotions, the report states.

Women are more likely to receive smaller raises than their cohorts, and less likely to be allowed to teach extra classes, for which professors are compensated, the reports and professors concluded. Careers thus generally move more slowly for women than men at the business school.

By the numbers

Out of a total 145 faculty members currently listed on the school’s faculty directory, some of whom are emeritus, just 26 faculty, including Dean Judy Olian, are women. None of the school’s 24 endowed or permanent chairs are women.

In 2012-2013, 11 women were ladder faculty, compared to 70 men, according to Academic Personnel Office data that Lawrence compiled.

The problem is not isolated to UCLA.

Women make up only about 18 percent of tenured teaching staff at seven top business master’s programs, including Stanford University and University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, according to Bloomberg Businessweek.

“It’s a pipeline problem,” said Ivo Welch, a finance professor at Anderson. “It’s a nationwide deficiency, definitely not just at Anderson.”

But while the realms of business and MBA programs are traditionally male-dominated, the recent report states that Anderson’s numbers of women faculty are low even against comparable business schools.

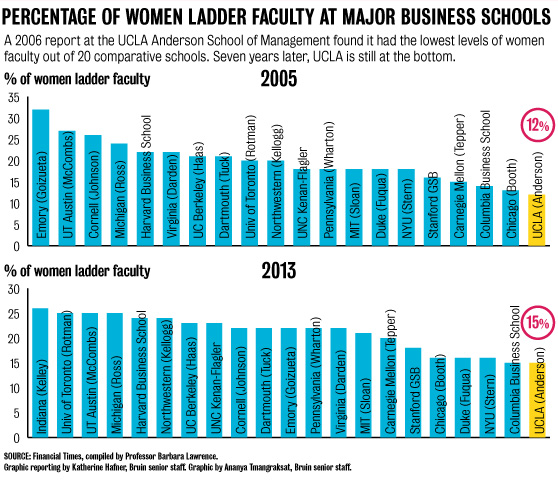

Anderson’s 2006 internal report by its gender equity committee found the school had the lowest numbers of women of 20 comparably sized and ranked business schools, including programs at Cornell, UC Berkeley, Dartmouth, Stanford and Columbia.

According to the report, the percentage resulted from low retention rather than discrepancies in hiring offers and recruiting.

Between 1980 and 2006, Anderson hired 131 faculty members, around 20 percent of whom were women.

But in the 2005-2006 year, Anderson’s women faculty percentage was at around 10 percent, leading committee members to question their retention rate.

Reviewers of the report in 2006 outlined several suggestions for starting to address the situation, including setting a goal for a percentage of women faculty for hiring and bettering retention rates, improving the teaching environment by reinforcing positive student attitudes and conducting more targeted studies, as well as a three-year follow-up study.

Nicole Biggart, a UC Davis Graduate School of Management professor and an external reviewer who helped author the 2013 report, said the distribution of women is also a concern, with clusters of women in certain research groups or departments creating a “female ghetto” effect.

Seven out of the 26 total female faculty members are in the management and organizations department, for example.

“They’re very good faculty, but there are parts of the faculty or clusters where there’s many one-woman faculty or none at all which is unusual,” Biggart said. “It creates a sense that perhaps women are not welcome there … and certainly the numbers suggest that that might be the case.”

Freeman, attributed some of the low numbers and clustered faculty to a lack of qualified women for business school faculty coming from lower levels of education.

If hiring practices were to continue as they do currently at Anderson, it would take more than a century for the level of women ladder faculty to reach 20 percent of the total, according to a statistical simulation by Lawrence and colleagues.

The question for administrators, then, is how to increase the numbers of women dramatically, given the limitations of a normal hiring cycle of about five people per year – and more saliently, improve the environment for existing faculty.

Changing the climate

In addition to suggestions for new positions to oversee gender climate at Anderson, the Academic Senate report recommends that the school works to change its evaluation process, including using more peer evaluations to supplement student ones. Reviewers also recommend follow-up studies.

Hughes said changes they could make were limited to the campus and women faculty were still subject to trends and attitudes of the larger academic community outside Anderson.

Anderson professors said they have noticed small efforts in recent years, like an increased focus on recruiting women, but they do not think it is a high priority for the administration.

“It’s not very effective, and I don’t think they think it’s very important,” said one anonymous female professor.

The three-year follow-up study recommended in the 2006 report was never completed, but Freeman said a new gender equity committee was formed earlier this year and is planning to present a new report by the end of the year.

Freeman stressed that the Anderson campus climate is something that all members of the school’s community need to be sensitive to and aware of.

But Welch said he doesn’t see how problems can be addressed by individuals.

“Faculty awareness is not the issue; faculty have been aware of these problems for decades,” Welch said.

Welch said the problems with diversity start in lower tiers of education, and the graduate level is too late to address them.

The Academic Senate report also criticized the minimal efforts made so far by the administration to address gender climate problems.

“Most of the response seems to have focused on ‘improving’ the women … rather than addressing the ways in which many women feel undermined by the school’s environment,” it states. “We don’t believe that the (gender equity problem) has the priority for the administration that it ought to have.”

Freeman disagreed with the report’s characterization of the administration’s response to the issue.

“We do place a high priority on gender equity and we have been working on this issue quite frankly since Dean Olian arrived here,” she said. “We know that it is essential to our academic quality and we take it very seriously.”

Lawrence said the school is not entirely to blame for the current campus climate because it is such an intensely complex issue and hard to solve, but that more can be done.

She referenced a study of gender climate at the science school at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, in which younger women told interviewers they weren’t having gender-related issues because that was only a problem for the previous generation.

“When they talked to senior women, they said, ‘That’s what we thought,’” Lawrence said. “That’s really a cautionary tale.”