Small UCLA reactor used by students shut down in 1984 because of potential safety hazards, declining use

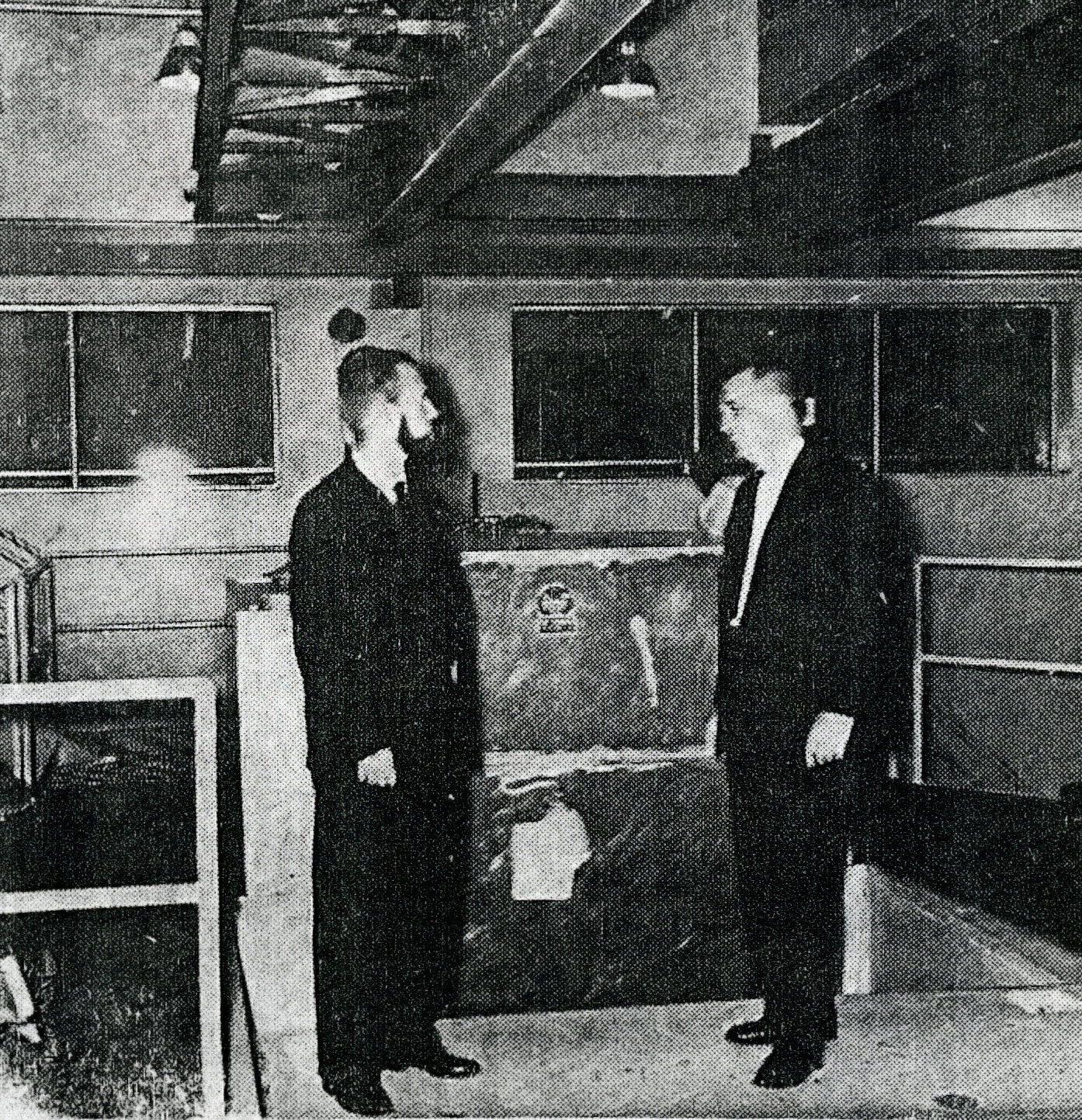

Thomas E. Hicks (right), engineering professor and then-chief supervisor of the UCLA reactor, and Ronald MacLain, his chief assistant, stand on top of the newly built reactor in December 1960. The nuclear reactor, which had the power of 100 toasters, was small and used mostly for research purposes.

CREDIT: UCLA ARCHIVES

By Neil Paik

March 30, 2011 1:22 a.m.

More than a quarter of a century ago, in the northwest corner of Boelter Hall, there was a powerful device guarded by large concrete walls that were off-limits to most students and faculty.

From 1959 until 1984, UCLA had its very own nuclear reactor, which was housed in the engineering building and utilized by various South Campus departments for research and business. While having reactors on college campuses is not a commonality, UC Irvine still houses a reactor that is substantially more powerful than UCLA’s was.

Installed when interest in nuclear power was high, amidst the chaos of the Cold War and arms race, the UCLA reactor was used mainly for research purposes. Undergraduate engineering students interested in nuclear energy received training on how to work the device and conducted experiments using the reactor. This entailed everything from learning how the device functioned to making medical and scientific breakthroughs by observing radiating isotopes, according to Ivan Catton, who was director of the UCLA Nuclear Reactor Laboratory and oversaw the device from 1976 to 1984.

The reactor was fairly small, about the size of a professor’s office, and had the power of 100 toasters, or 100 kilowatts, said Catton, who still serves as a professor of engineering. Despite this, Catton says some of the uranium housed within the reactor was 93 percent enriched, which is at the same level as bombs.

The device did not garner community criticism until 1979, when it came up for re-licensing. This process gained attention because the Nuclear Regulatory Commission became involved, as it generally does with issues regarding nuclear power.

With this process came greater ethical concerns voiced by anti-nuclear organizations who questioned the safety of the reactor’s on-campus presence.

According to Catton, this was the death sentence for UCLA’s reactor.

One group, the Committee to Bridge the Gap, voiced protests for five years until the reactor was finally de-commissioned in 1984.

Catton recalled one video broadcast on television that showed a young girl eating lunch by a radiation sign, implying that the reactor was hazardous to students’ health.

But he insisted that enough safety evaluations were done before the installation of the low power reactor to make certain that no such hazards would be present.

“You certainly could get into trouble, but it would have to be very deliberate. … I think it was unwarranted,” Catton said.

Though the protesters had a voice in causing the reactor’s demise in the early 1980s, it was not the only reason to decommission the device.

George Turin, dean of the engineering school at the time, said he appointed a commission to evaluate how much the reactor was utilized.

The results showed it was used only 10 percent of the time during the year and was scarcely used by the School of Engineering for classes for research.

This was the official reason chosen by former Chancellor Charles E. Young to decommission the reactor.

In 1984, it was taken apart piece by piece under government supervision and disposed of. The process of disposal was itself dangerous and “a little James-Bondish,” Turin said.

The hazardous fuels were placed in lead containers in the middle of the night and shipped via trucks to various repositories. Though there was fear that someone would get word of the transfers and attempt terrorist activity, no such events occurred.

The interest in nuclear energy has since declined among students and faculty, said Vijay Dhir, dean of the School of Engineering and Applied Science. In the likely event that there is increased interest in nuclear energy, the school would create a program for graduate students to conduct research, he said.

“Nuclear energy was downsized,” Dhir said. “But in the long run … I think the country will have to rely on nuclear power.”