(Christine Rodriguez/Daily Bruin)

By Katarina Baumgart

March 14, 2025 at 11:02 p.m.

Social media led Annie Wong into an unexpected world of crimson-tinged activism.

In her conservative household, discussions about menstruation were considered taboo. Coupled with less-than-thorough health classes at her Texas high school, Wong had limited access to period education before social media existed. As she grew older and learned more about the harmful effects of period stigma, Wong decided to push back against this silence, exploring menstruation euphemisms through her art on Instagram.

“I wanted to make something that was talking about this taboo, … potentially feminist thing in a funny way,” Wong said. “That was the seed of that idea, and I was really surprised by how it took off.”

From wave-surfing menstrual cups to smiling red blobs, Wong, now a lecturer at California State University, East Bay, decided to use Graphics Interchange Format, or GIFs, to foster discussion around menstrual health in 2018. Since then, her GIFs – such as “Surfing the Crimson Wave” – have garnered over 61 million views. But for Wong, seeing the positive impact of her work through interactions with people means more than the online metrics. In moments with an appreciative gynecologist or a father buying uterus stickers for his daughters, she realized social media and art could be a platform for building menstrual awareness and connection – not only between her and her fans but also with viewers’ friends and families.

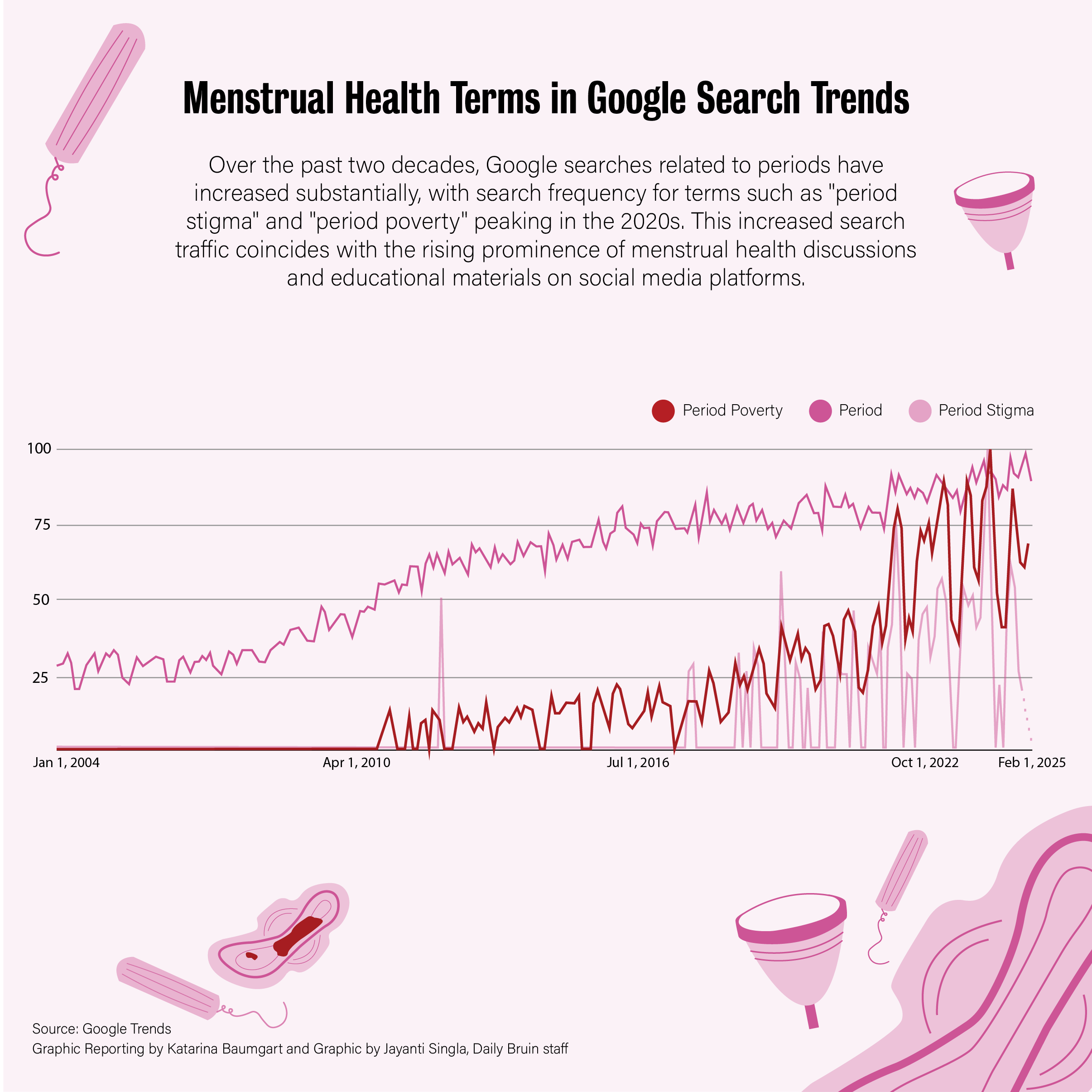

Social media content like Wong’s is part of an increase in online conversations about menstruation. In response to medical gaslighting and insufficient education in schools, many influencers, activists and scholars have started addressing period taboos and sharing their experiences through lighthearted and educational content. While misinformation remains a concern, many users across the globe have continued to build digital communities that provide space for education and the empowerment of menstruation online.

According to the Guttmacher Institute, a nongovernmental organization that conducts research on sexual reproductive health, only 36 states and Washington, D.C. require sex education, HIV education or both. This means many young people are not receiving comprehensive education about their sexual reproductive health.

Dr. Cara Natterson, a pediatrician and author of “The Care and Keeping of You” series, said that while biology-centered education is integral to building understanding, it can often bypass students who respond better to engaging videos or podcasts about the real-life experiences and concerns of menstruation.

“The only successful way to offer preventive health is to do it in a way that combines both biology and physiology on the one hand and real life on the other,” Natterson said. “If you don’t do both, you’re going to miss a lot of people.”

Over the past decade, users have started engaging with social media to fill this knowledge gap. Conversations around menstruation have surged in popularity on online platforms such as Flow Space, a women’s health media platform, whose advertisement “The Camp Gyno” went viral in 2013 with 14 million views on YouTube. In 2015, poet and performer Rupi Kaur posted pictures of blood on her pajamas and bed sheets for a photography project, which went viral after being censored by Instagram.

Maria Tomlinson, a lecturer in public communication and gender at University of Sheffield, researches how public communication influences perceptions of social inequalities and health. Tomlinson said social media and news coverage about periods – from Kiran Gandhi free bleeding while running the London Marathon to Kaur’s Instagram posts – sparked her interest in researching the media’s impact on menstrual stigma and education.

“I thought, ‘I wonder what impact all of this visibility has had,’” Tomlinson said. “Has it actually reduced menstrual stigma? Have young people’s knowledge about it improved? Are they talking about periods now?”

Through her interview-based research, Tomlinson found that young people said online conversations about menstrual experiences broke down their feelings of isolation and also empowered them to have conversations about their periods, even in mixed-gender spaces. This was especially true for expressing menstrual cramp discomfort in front of boys, which they felt free to do without backlash.

“The young people I spoke to were so free to have the opportunity to talk about periods, including the boys, and they were more confident toward periods than I had been at that age – or anyone my age had been,” Tomlinson said.

That exposure to period posts has continued even as platforms have changed.

Natalia Zeledon, a fourth-year English student and co-president of Period at UCLA, said her exposure to online menstruation education was a byproduct of TikTok’s increased popularity during COVID-19 quarantine.

“I started to learn a little bit more about how my mental health and well-being can influence my menstrual cycles,” Zeledon said. “It’s influenced me at least for the better because some of those topics, like mental health and menstrual cycles, aren’t really talked about in schools – at least when I was growing up.”

Zeledon turned to social media after feeling invalidated by her doctor, who proposed losing weight was a blanket solution for her menstrual issues. She shared that implementing the breathing techniques, exercise and nutrition tips she encountered online not only improved her menstrual cycle but also her mental health.

Tomlinson said social media exposure and menstrual health organizations have collectively increased awareness about medical conditions like endometriosis and initiated calls for the need to further improve the United Kingdom’s health care system.

“There’s still medical gaslighting, where women are not believed because they’re in a lot of pain,” Tomlinson said. “Some doctors will just say, ‘Oh, really, it’s normal that you’re having a really painful period.’ So women have to really know how to advocate for themselves, which can be really hard.”

Nicole Bendayan, a self-proclaimed women’s and menstrual health expert, experienced this gaslighting firsthand. For three years, she repeatedly sought help from medical doctors because of negative symptoms caused by her birth control. After being dismissed by four doctors, Bendayan said she turned to online research studies and started learning about hormonal cycles and cycle syncing – something that she wasn’t aware of before.

Bendayan, who now posts educational content about periods, said social media has built a sense of responsibility to advocate for her followers. In validating their medical struggles, these platforms remind those who menstruate that menstrual pain does not have to be a part of their existence and that they don’t have to suffer in silence, she said.

Social media also opens up conversations about a breadth of experiences and identities that are not often discussed in mainstream media or educational institutions. Tomlinson said accounts can focus on the impacts of health conditions such as fibromyalgia or endometriosis or the experiences of disabled, transgender and nonbinary people. The depth of experiences that are acknowledged online allows many individuals to find communities that are not acknowledged in formal education, she added.

Content creation can also be validating, Wong said. She found that animating GIFs online has helped her develop a more positive attitude toward her body. Rather than viewing periods as a bodily inconvenience, art has allowed Wong to reclaim her menstrual experience into a narrative she owns. She added that personifying her uterus as a character through her content allowed her to feel sympathy for rather than frustration with her body.

Aditi Gupta, a co-founder of a menstruation destigmatization initiative, also highlighted the importance of having a positive relationship with one’s menstrual cycle. She said it not only contributes to building a better life but also improves physical and mental health.

“Having a positive relation with your own body is probably the most decisive factor on how amazing a life that you are creating, how healthy you feel in your body, how healthy you feel in your mindset and within yourself,” she said.

The surge in menstrual visibility online has led to real-world accessibility to medical resources, both abroad and locally. Sisi Peng, a doctoral student at UCLA researching health communication and women’s health issues, commented on the power of social media to raise awareness about period poverty – which UN Women defines as “the inability to afford and access menstrual products, sanitation and hygiene facilities and education and awareness to manage menstrual health.”

“Social media can help raise awareness of people in places where there is inadequate or lack of access to period products,” Peng said. “There’s been a lot of great nonprofit organizations, like The Pad Project, which is actually based in LA, that collects and donates period products and then gives them out to communities in need.”

Groups across UCLA similarly promote education, community and access to menstrual health products. The Pad Project’s UCLA chapter organizes workshops for community building and menstrual health awareness. Another student-led organization, Period at UCLA, donates products to the BruinHub for commuter students and is planning hybrid workshops exploring the intersection between menstruation, queer mental health and social media. Days for Girls at UCLA donates roughly 400 period kits every quarter to unhoused individuals and local women’s shelters and conducts presentations to educate students about menstrual health.

Kaitlyn Shimohara, a fourth-year human biology and society student and the president of Days for Girls at UCLA, added that it also sends period kits to the organization’s international branch, which donates them across the globe. These efforts help mitigate period poverty in countries where sanitary products and education are not always accessible.

The menstrual education movement is growing outside of the U.S. as well.

Gupta, who grew up in India, explained that periods are often associated with being impure in South Asian countries, leading some religious institutions to ban women from entering when they are menstruating. In response to controversies like these, she created Menstrupedia, which hosted one of the first blogs in India focused on menstruation, in 2012. Gupta said content like this – and the internet as a whole – increases conversations around menstrual health, which are often controversial or not widely discussed. Amplification of these messages can contribute to discourse in government about health policy, she said. Menstrupedia is active on Instagram today with more than 100,000 followers.

“Internet is such an exciting place right now. For us now, how can we use it to have the conversations which were otherwise taboo but now accessible to you in a way that … is more consumable, in a way that is sensitive, it is given to you in a way where you understand it?” Gupta said.

Vivi Lin, a period equity and sexual reproductive health and rights activist, added that social media is important for building awareness around menstrual health disparities in Taiwan.

“When we first started, there was no definition in Mandarin on period issues. So, for example, there wasn’t a word called ‘period poverty’ in Mandarin,” Lin said. “At that time, we used social media heavily because social media helped us a lot in terms of spreading the information, in terms of raising awareness across the Mandarin-speaking world.”

Lin said she created the world’s first period museum, The Red House, in 2022 as a space to educate people about period equity and highlight art exploring the subject. She wanted to create a welcoming space for people to learn more about menstruation – or have their questions answered for the first time, as was the case for many visitors. Since then, over 10,000 visitors from 30 countries have visited the museum. Its art collection has highlighted performances, written work and visual art from across the world, capturing a breadth of experiences across diverse mediums and cultures.

Although period poverty is often acknowledged in low-income countries, Lin explained that high-income countries are not devoid of period poverty or stigma.

“It’s really hard to raise awareness and to make people aware that this can happen in your neighborhood,” Lin said.

Although social media has provided a platform for sharing period resources and increasing visibility, there are dangers in relying on online content for information. Natterson highlighted these risks, especially for younger audiences.

“Sometimes viral content is not reliable content,” she said. “Sometimes there’s fear mongering. Sometimes there’s just urban mythology that circulates on platforms, and social media makes it really, really easy for information to spread – good or bad.”

When young people rely too much on social media for their period education, they can absorb harmful misinformation, Tomlinson said. Institutions can break the cycle of stigma by increasing students’ critical media skills and menstrual health literacy, she said, which will equip young people to better judge whether information they encounter online is accurate.

Sofia Hollstein, a co-president of The Pad Project at UCLA, added that social media provides a valuable starting point for awareness but that more must be done to advance these efforts.

“It’s good to have exposure and good to have conversations,” the first-year cognitive science student said. “But what we’re really missing right now is that second step that comes after the exposure, and where do people go next after seeing this information.”

Organizations, researchers and activists across the world are working to bridge that gap between online activism and on-the-ground work. Bendayan creates social media content but also developed an online learning platform and offers to help clients navigate discussions with health care professionals. Lin established the first Taiwanese general education course on menstruation at National Taiwan University, while her organization With Red trains schoolteachers in period health education and helped pass the first policy in Asia requiring schools to provide period products on campus. And Gupta created “Menstrupedia Comic” to provide menstrual education in a culturally sensitive manner, which she said has empowered young women to teach younger girls about periods in India and 11 other countries.

Even with these on-the-ground and interpersonal efforts, Wong still finds value in social media. It is where she – and many others – have found information, community and greater well-being. She continues to post and is planning to expand her content into related topics, such as menopause.

For Wong, efforts to rewrite, reclaim and recenter menstrual education in digital media are a form of empowerment – and she hopes to help other people recontextualize their own experiences through her work.

“This is the power of owning a narrative, or storytelling, which is what I think about a lot when making art,” Wong said. “You can have your own interpretation of what it is. It doesn’t have to be what your high school gym teacher told you what it is. … It could potentially be a more positive experience.”