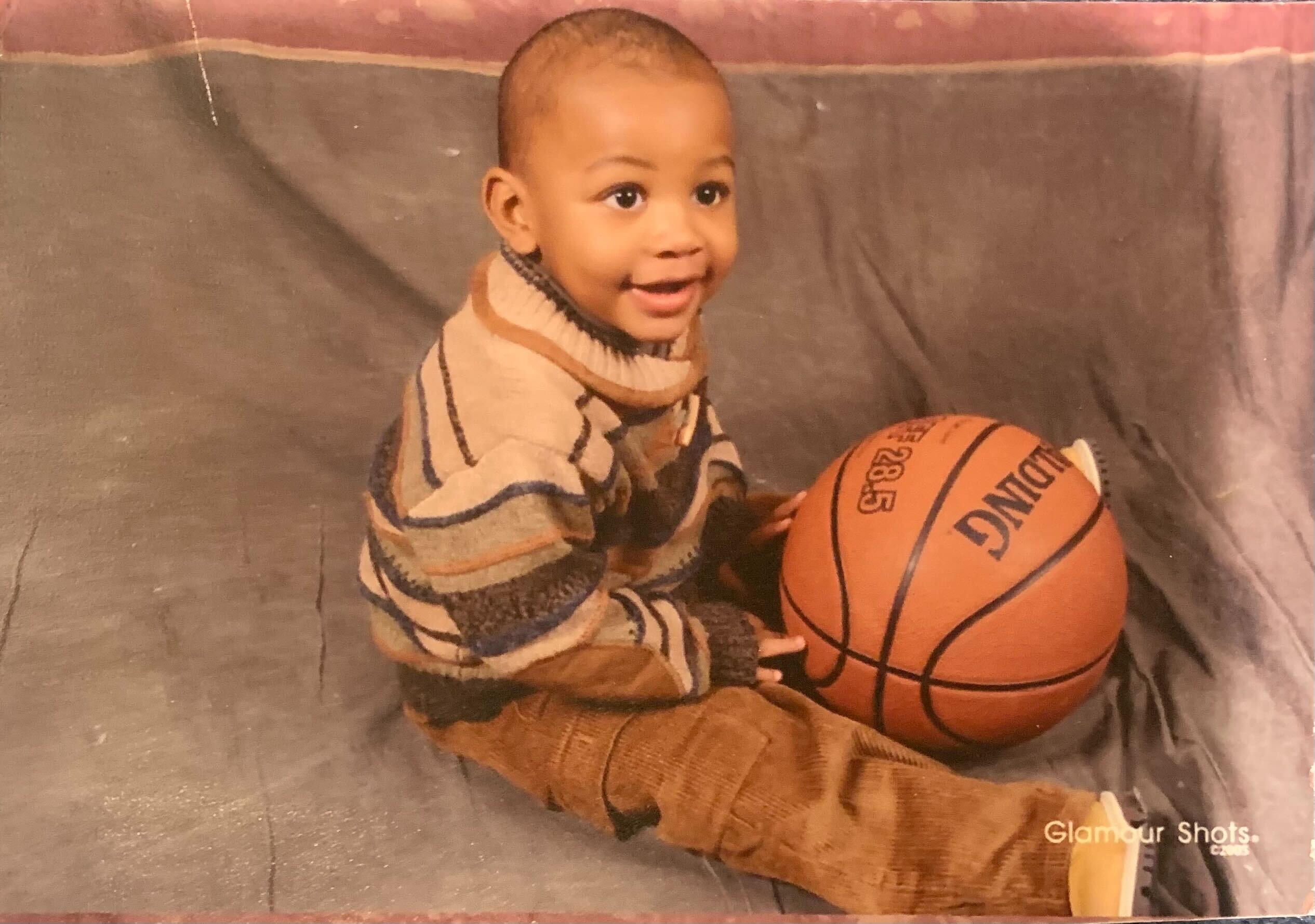

UCLA men’s basketball sophomore guard Sebastian Mack is featured. (Photos by Aidan Sun/Assistant Photo editor. Design by Lindsey Murto/Design director)

By Ira Gorawara

March 17, 2025 at 10:31 p.m.

Blood dripped from his nose. His coach signaled for him to step off. His mom urged from the stands. But Sebastian Mack wasn’t going to budge.

Nothing was pulling the sixth grader off that court. Not until he sunk his freebie.

“That’s when I was kind of like, ‘OK, is he crazy?’ To see him be bleeding and still want to finish what he had to finish,” said Mack’s mother, Leslie Johnson. “He stayed in there until that was done, and now I’m thinking, like, ‘OK, he must really like this basketball.’”

It was less of a revelation and more of a preview for Johnson.

Because the now-UCLA men’s basketball sophomore guard wasn’t just a kid who loved basketball. He was a kid who refused to let anything take the ball out of his hands.

And that has yet to change.

It hasn’t in college, when he fought through a season with an injury so severe that Johnson struggled to watch. It didn’t in high school, when recruiters pinpointed that his fearlessness was as sharp as his game. And it certainly didn’t as an eight-month-old, when he bypassed crawling altogether and decided to stand up one day and start walking.

“I remember being at Chuck E. Cheese or something, and I’m letting him walk. And this man walked to me and said, ‘How is he walking? He looks like a lap baby, like you should have him in your arms right now,’ and I’m like, ‘I know’, but I don’t know – he just started walking like he wanted to walk. When I tell you he never crawled, he never crawled,” Johnson said.

It was as if life was already daring him to move faster.

And Mack’s mother – whom he calls his best friend – recognized a fire in him and the wild energy that needed an outlet.

A former collegiate track athlete herself, Johnson knew Mack’s “rambunctious” spirit had the potential for glory. She molded his competitive nature with discipline that leveraged his ferocious traits.

“When I would do my workouts, I would take him to the track – I would run, he would run,” Johnson said. “He typically wanted to bring a basketball – it took some of that energy out so we can have some rest in the evening. I had to take him to run. He had to get on the track and get some of that energy out.”

Johnson, with a sharp eye honed by the world of professional sports and watching Mack’s father compete professionally, knew she had to harness her son’s raw potential early.

“I always made sure he was working out more than the other kids were because I know that gives you the competitive edge,” Johnson said. “I promised, ‘If you handle this, or if you get an A on this, then I’ll take you to the gym.’ … I’m taking my time and I’m making sure you get to the gym, so when you get out there to compete, I expect you to be the best.”

And Mack’s edge has never lost its bite.

Coach Mick Cronin, whose roots trace back to Cincinnati, about 250 miles from Mack’s Chicago stomping grounds, recognized his hunger to dismantle defenses and drive to bend the game to his will. Cronin, who doesn’t fall for glitz, was drawn to Mack’s combination of finesse and force – he was a kid who didn’t flinch when his opponents towered over him.

Two seasons later, that relentless pursuit has led Mack to a new title – the on-the-court “assistant coach.” He’s Cronin’s right-hand man during practice, calling shots that echo beyond the playbook.

“We’re the two most intense Midwest guys in the gym,” Cronin said.

Despite a sixth-man role, heads turn down the bench when UCLA is starving for a backcourt presence.

In UCLA’s Nov. 20 showdown against Idaho State, Mack was a hot knife through butter.

Fifteen free throws supplemented his 21 points and an 84-70 Bruin win. And the “Mack Attack” was born in the Bruins’ Big Ten debut 13 days later. A concoction of precision drives, tenacious boards and smothering defense led the Bruins to hound the Huskies.

“It’s more instinct,” Mack said. “You’ve seen it. You know how to exploit it. Seen it so many times, it’s like repetition.”

Sixty-eight seconds ticked on the clock, and a rivalry game teetered on the edge Jan. 27. And against the Bruins’ fiercest rivals, Mack’s fiercest side emerged.

Mack danced with his defender before launching a deep 3, backpedaling as it sailed cleanly through the net. It was the knockout punch, ultimately silencing any hopes of a USC comeback.

Mack’s unflinching resolve in the dying embers of battle reverberates louder than any play call – forging an understanding with his coach that requires no verbal confirmation.

“We could talk mentally – just give each other that look, and we already know what is it,” Mack said.

The thing about Mack is that he doesn’t just wait for the ball. He calls for it. Even when his body is begging for respite.

After just four games last season, Mack was hit with a turf toe injury.

Did he sit out? Not a chance.

“I really had a hard time watching him play because I’m seeing him hopping around the court,” Johnson said. “That was tough. But that made me look at him like, ‘You really are a tough guy.’ And I tried to convince him to sit out, just take some time. And he never did.”

And while no one can force him off the hardwood – not even his mother – Johnson’s voice is the constant soundtrack in Mack’s head.

“She wanted to always put me in positions to where I can thrive,” Mack said. “She kept instilling in me that you got this, giving me affirmations. And I feel like that’s what helped me boost my confidence.”

There’s no bravado in Mack’s game. It’s something that has been edited and refined through 21 years of drafts.

His drive has yet to take a break. Because when a moment calls for hesitation, Mack knows just one solution.

Step forward.

And take the shot.

“Sebastian has been Sebastian since birth,” Johnson said. “He came out tough. And he gave me that to work with.”