Photos by Jeremy Chen/Daily Bruin senior staff. Photo illustration by Helen Juwon Park/Daily Bruin.

By Samantha Parr, Mridhula Thyagarajan, Rachel Rothschild, Lori Garavartanian

February 2, 2024 at 10:58 a.m.

Out of the nine total disability specialist positions the Center for Accessible Education typically maintains, only three were filled at the start of the 2023-2024 academic year.

The CAE helps thousands of undergraduate, graduate and professional students obtain the medically necessary academic accommodations they need to succeed and learn. The office’s disability specialists are supposed to guide students through the process of selecting and applying for classroom workarounds and aids specific to their disability.

However, an investigation into UCLA’s CAE – during which the Daily Bruin spoke with a total of 12 students and alumni who have requested accommodations from the office – revealed widespread dissatisfaction stemming from the office’s severe understaffing. Left unsupported by the office, students feel that they are forced to advocate for themselves in order to get their accommodations.

The CAE office repeatedly declined the Daily Bruin’s requests for an interview, opting only to answer a list of fact-based questions in an emailed statement.

The CAE has been stretched thin for years. Last fall, three specialists served 3,843 registered students, resulting in a ratio of 1,281 students per specialist – 1,148 more than the national average of 133 students per disability specialist.

Three new specialists began working for the office in mid-October, bringing its total up to six. When all nine positions are filled, each specialist manages an average caseload of 360 to 400 students, according to an emailed statement from Spencer Scruggs, the director of the CAE. But, with three remaining vacancies throughout fall quarter, the office relied on temporary specialists and other staff to balance the caseloads.

Staffing shortages also forced the CAE to institute procedural changes. According to minutes from an Oct. 10 UCLA Committee on Disability meeting, the office stopped assigning students to individual disability specialists, leaving registered students unable to access personalized support for their specific needs and accommodations.

Vivek Chotai, one of the students not assigned to a disability specialist at the start of fall quarter, said he was concerned that it would be difficult for students to communicate with the office if they needed to make adjustments to their accommodations.

In his first year, Chotai successfully coordinated his housing accommodations with his assigned disability specialist. Now, he and his peers are struggling to get responses from the CAE, Chotai said.

“If we have questions or another flare-up or something that we want to ask about, we don’t really have a point of contact anymore,” said Chotai, a third-year molecular, cell and developmental biology student. “We’re not supervised at all.”

Scruggs said in the emailed statement that the CAE hired three more specialists at the start of winter quarter, filling the remaining vacancies.

From Chotai’s perspective, high staff turnover is a long-standing issue for the CAE office. In approximately two years, he has been assigned to three different disability specialists, as newly hired specialists have quickly quit or left for new positions, he added.

“It’s just a fact that CAE doesn’t have enough people,” Chotai said.

While Chotai received the necessary accommodations his first year, he said other students who applied that same year did not receive the necessary accommodations. The delay in communication from the CAE this past quarter due to the staffing shortages is now exacerbating the issue.

According to Scruggs’ emailed statement, the average caseloads in recent years were 700 to 850 students per specialist in the 2020-2021 academic year, 600 to 800 for 2021-2022, and 450 to 500 for 2022-2023 – all consistently above the professionally recommended ratios.

Nina Zamora, an alumnus who graduated in 2021, said the CAE office had insufficient staff throughout her time at UCLA. Zamora, who needed accommodations for post-traumatic stress disorder, said she had an especially difficult time seeking support when her specialist was out of the office and the CAE did not assign anyone to fill in.

Quinn O’Connor, one of the co-founders of the UCLA Disabled Student Union and an alumnus who graduated in 2022, said the lopsided ratio of students to specialists makes it difficult to provide students with personalized attention. Because they are juggling so many cases at once, they often cannot recall the specifics of any given student’s situation, added Katie Bogue, a fourth-year biochemistry student.

“All of the disability specialists are stretched incredibly thin,” Bogue said. “They don’t have enough time to do their job.”

Caitlin Solone, an academic administrator for the UCLA disability studies department and member of the CAE Advisory Board, said the high rate of turnover and chronic understaffing in the CAE is largely attributable to the low salaries provided for disability specialists. According to annual wage data reported by the UC, the average pay for a disability specialist at UCLA in 2022 was $35,788. In comparison, the average pay for disability specialists was $54,607 at UC Berkeley and $79,600 at UC Davis.

These offices not only offer higher wages but also employ a similar or even larger number of specialists. As of Jan. 29, UC Berkeley had 13 disability specialists, and UC Davis had seven disability specialists.

Among other California schools, UC salary grades fall below both the CSUs and California Community Colleges, said Laura Riley, director of the UC Riverside Student Disability Resource Center. These low salaries also make it difficult for the UCs to compete with other campuses in the hiring process, she added, which in turn plays a role in the understaffing issues experienced across UC disability services centers.

Bogue, who first registered with the CAE before the start of her freshman year, said the initial application process to receive accommodations took months. The doctors and specialists she worked with were often busy with other duties or did not always know the exact language that was needed to ensure that the documentation was completed correctly. Once she was able to submit her documentation to the CAE, she still had to negotiate the number of her needs that would be accommodated, she said.

“It was brutal – it was long and time-consuming,” Bogue said. “I had to spend countless hours coordinating with doctors and specialists to try to get the right documentation.”

Hilary Wu, a human development and psychology doctoral student, said she submitted paperwork to receive CAE accommodations in early July of last year and only heard back when she followed up in September, leading to unnecessary anxiety and worry.

Staffing shortages are not the only concern for registered students. In the fall, the CAE began requiring students to sign up for each of their exams on the CAE’s online portal at least seven days before their test. Prior to this change, professors requested testing accommodations for their students, according to the CAE website.

Madelyn Kelly, a third-year political science and public affairs student as well as a member of the CAE Student Advisory Board and DSU, said if students are unable to book the exams through the portal before the seven-day mark, they must work with the CAE further to see if they can still receive accommodations. If the CAE is unable to work out testing accommodations for those who need them, such as the location for their exam, students may need to take the exams without the accommodations, Kelly added. Professors can also, under rare circumstances, offer separate exams for students in their class who need accommodations.

Bogue said the time required to complete the CAE’s accommodations request processes disadvantages CAE students in comparison to their peers.

“Most able-bodied students are not having to juggle, on top of their classes, multiple doctor’s appointments every week,” Bogue said. “When you add, on top of all of that, time spent just trying to get access to the classes that you’re paying for, you’re left with even less time to actually spend on those classes.”

Under certain circumstances, Bogue said, professors may change the format or content of the tests within the seven-day deadline. For example, at last-minute notice, a professor could give an exam midterm instead of an essay, which could cause issues for students who need to book their exams to receive the necessary testing accommodations.

Julia Alanis, a fourth-year music history and industry student, said that last summer, she had to drop a class because CAE disability specialists were not available to help her request an extension for one of her assignments. Her specialist was transferring to another job, and she was later assigned to a second specialist who was also in the process of leaving, Alanis said.

“I couldn’t find somebody to contact,” Alanis said. “I ended up just dropping the class because I thought it was easier than trying to find somebody to help me.”

However, self-advocacy – the only other option when specialists are unhelpful – places an unnecessary burden on students, Bogue said. She added that the time and energy required to advocate for herself by collecting documentation to show both the CAE and professors has been taxing both mentally and physically.

Kelly said students may be busy fighting for accommodations instead of properly focusing on academics. Despite being an institution that is supposed to advocate for students with disabilities, the CAE normally fails to do so, added Tessa Fier, an alumnus who graduated in 2023.

“Your first job is just to be a normal student with a disability, which is already exhausting on its own,” Fier said. “On top of that, you have to advocate for yourself.”

Some students said they had better luck bypassing the CAE office entirely and speaking directly to professors, Bogue said.

Fier’s professors, on the other hand, were generally either unwilling to help or did not have the ability to provide specialized accommodations without additional support from the CAE or the university, she said. Fier, who required virtual and hybrid learning formats for illness-related accommodations, said one professor stopped responding to emails about her accessibility concerns entirely after becoming frustrated by her requests, despite continuing to respond to emails from other students.

Gwendolyn Hill, a fourth-year psychobiology student, said it is taxing to reach out to professors and then be denied accommodations.

“It’s been very, very frustrating and emotionally draining, and honestly, I would say relatively traumatic to try and reach out,” Hill said. “It’s all reliant on what the opinion of the professor is, and if they say no, then they say no.”

Solone said that the university needs education for all faculty related to universal design for learning and how to make their classes more accessible so that students don’t have to continuously advocate for themselves in the first place.

As specialists come and go, Fier said the difficulty of constantly reintroducing and re-explaining her disability has also taken an emotional toll, often causing her to question whether she ever deserved accommodations.

Even when students can find a specialist to help, Fier said, the kind of help they offer may not be sufficient.

When she entered UCLA in 2018, Fier requested virtual access to classes on days when she was too sick to attend in person. However, Fier said her assigned disability specialist often failed to communicate her absences to her professors in a timely manner. As a result, Fier said she had to email professors on her own.

Victoria Marks, the chair of the UCLA disability studies major, said the Americans with Disabilities Act, which informs the types of accommodations granted by the CAE, does not include all of the disabilities that students may experience. As a result, universities like UCLA are often unprepared to handle specialized accommodations, she added.

Bogue, for instance, said the CAE has pushed back on her requests by saying that they don’t offer the accommodation that she requested. Despite her high school granting accommodations such as taking breaks and pausing the clock as needed during her exams, the CAE refused to provide the same – claiming the best they could do was offer her extra time.

“Accommodations are not a menu of offerings from a restaurant that you sit down at a table and order,” Bogue said. “They’re specific to the individual student.”

Alumnus Megan Borella said she resorted to legal action after UCLA failed to provide adequate accommodations for her blindness. Borella, who graduated in 2020, filed a case with UCLA’s ADA/Section 504 Compliance Office in 2018, alleging that the CAE neglected its responsibility to provide braille and related resources for one of her classes, according to documents reviewed by The Bruin.

The compliance officer assigned to her case determined that UCLA failed to provide Borella with adequate alternate and timely format materials. Borella, alleging that UCLA continued to deny her meaningful access to education despite the outcome of the grievance, filed a lawsuit against the UC Regents in late 2019. In the complaint, Borella’s legal team argues that she suffered significant anxiety, frustration and depression as a result of the university’s failure to provide accessible materials.

The university’s representation – which made clear they did not intend to reach a resolution on Borella’s case – demonstrated a combative attitude that only proved to Borella that the university was not willing to meet her halfway and had no intention of making any changes to increase accessibility for students with disabilities, she said.

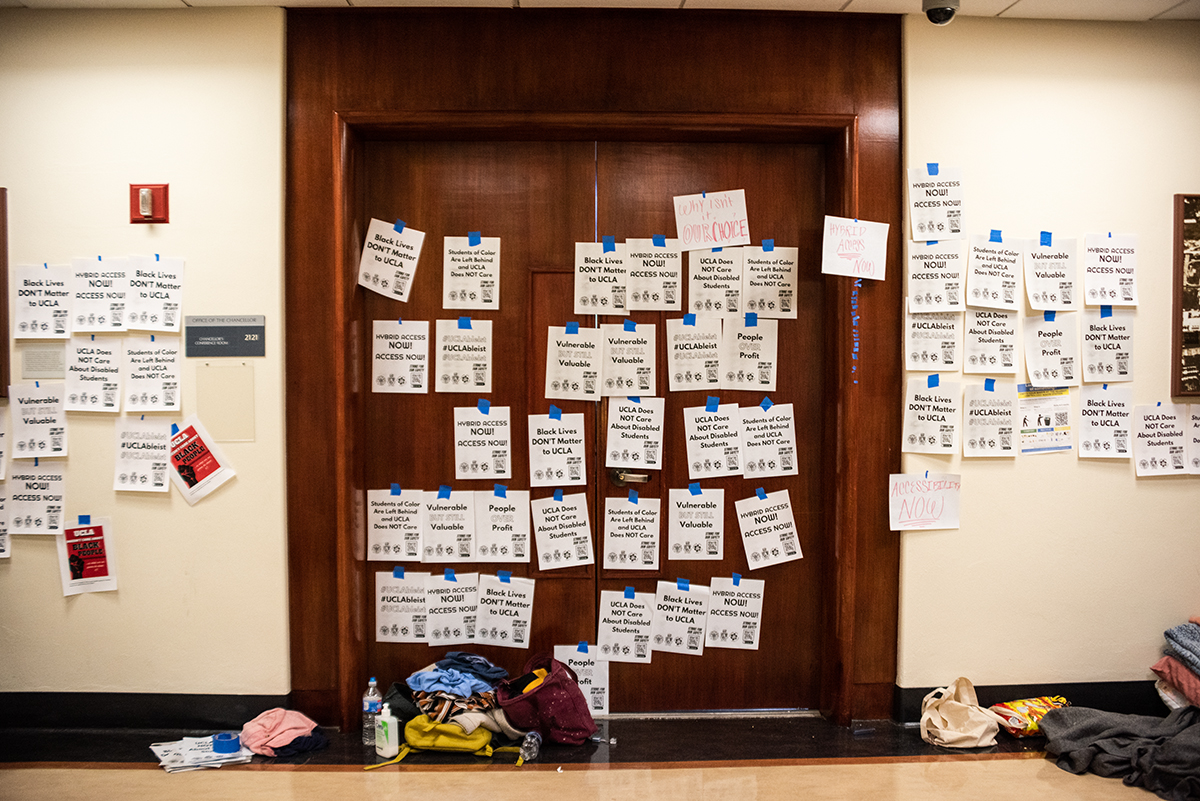

Echoing Borella’s frustration, O’Connor and Fier said they see limited pathways for achieving real change.

Fier said she only sees two viable solutions: a coalition-based approach to educate more students about disability issues or a class action lawsuit. O’Connor added that they believe mass legal action needs to be taken against the UC Regents to bring about fundamental reform.

Solone said she believes allocating more funding for the CAE could be a first step to encouraging improved student support from specialists.

“The only way that things are going to change is if people who aren’t disabled start caring and if the way that the pressure is being applied threatens UCLA’s prestige or money,” Bogue said.