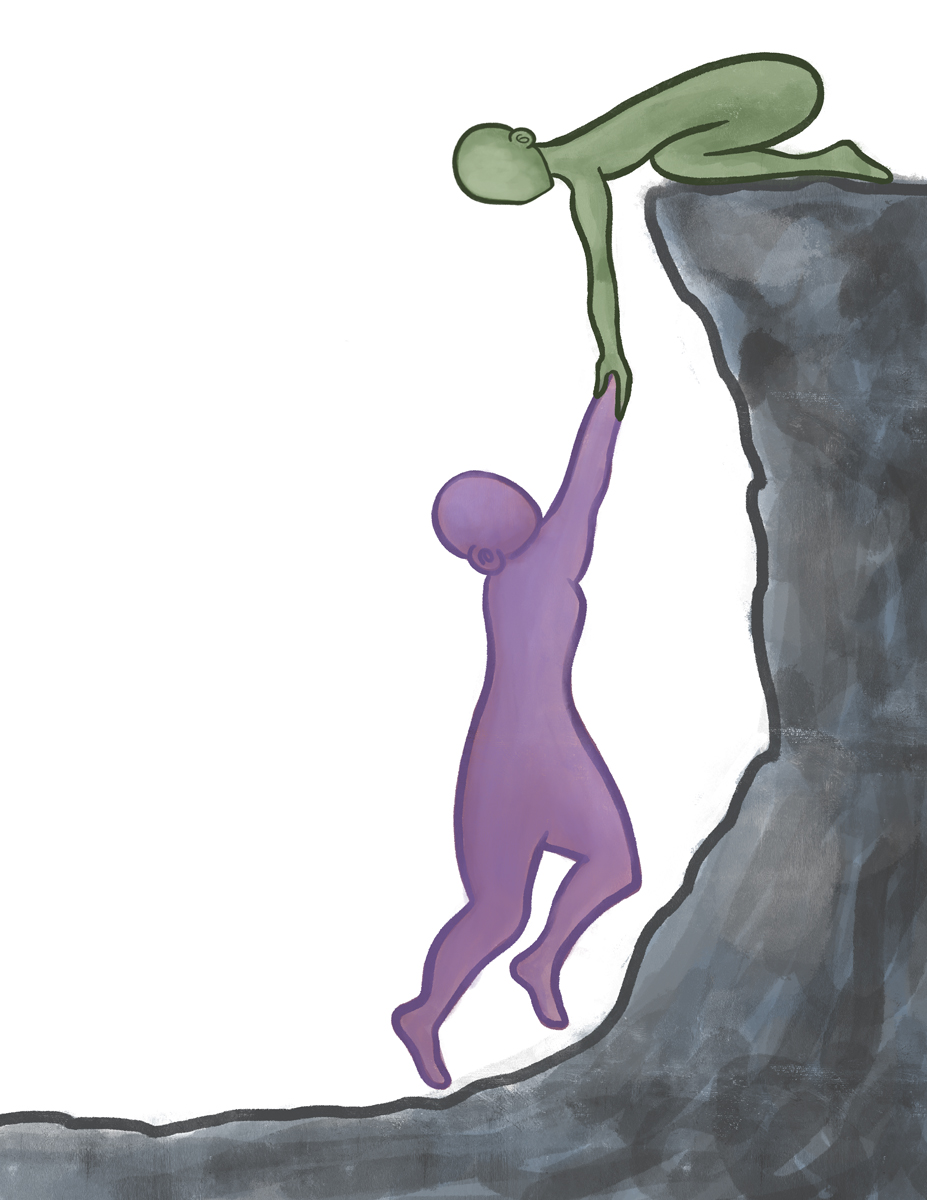

(Megan Fu/PRIME Art director)

By Mitra Beiglari

September 25, 2022 at 10:44 p.m.

This post was updated Sept. 29 at 6:05 p.m.

Jaymie Park had not considered her United States citizenship status until she applied for college financial aid.

It was 2011, and Park quickly realized she had few options for financing her education as an undocumented student. In the face of mounting bills and expenses, she was forced to take a leave of absence.

Park eventually returned to UCLA – once to finish her undergraduate degree in 2015 and again to pursue her current masters program at the Luskin School of Public Affairs. While paying for graduate school has proved to be an even greater challenge than undergraduate degree, Park has since realized she is not alone in her struggle.

In 2009, UCLA’s Undocumented Student Program emerged as a key source of support for students similar to Park. One of the first college programs in the nation dedicated to supporting undocumented students, USP provides comprehensive legal, academic and financial services to individuals throughout their UCLA careers.

Paolo Velasco serves as the Director of the Bruin Resource Center, which has housed USP for over 10 years. Although USP started off small, its staff has since grown to include an attorney, a paralegal, a program director and an associate director, Velasco explained.

As an immigrant himself, Velasco knows firsthand the importance of education – his single mother attended college in order to become a nurse and support the family. But higher education remains elusive for many undocumented students, Velasco said.

“It’s such a significant thing, to not have the same access to resources and experiences as other students,” Velasco said.

In 2012, former US President Barack Obama announced Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals. DACA has since provided undocumented individuals who arrived in the U.S. at a young age with work permits and protections against deportation. However, while DACA can enable students to work taxable jobs, it still does not qualify them for federal work study – a key source of financial aid for roughly half a million students in the country.

At the same time, DACA recipients are at the mercy of state laws determining if they qualify for in-state college tuition.

Even before federal protections for undocumented students emerged, California passed Assembly Bill 540. The law allows undocumented individuals to qualify for in-state tuition at California community colleges and public universities after meeting certain coursework or degree requirements. Students who qualify for AB 540 can also apply for funding provided by the California Dream Act, which allows undocumented students who live in California to receive state financial aid, university grants and scholarships.

Both state and federal policies played a critical role in Park’s undergraduate years. After qualifying for DACA, Park used her newly granted work permit to find a part-time job. Her employment, along with state aid from the California Dream Act, enabled her to end her leave of absence from UCLA and return to campus.

Yet, Park’s financial challenges were far from over. In her first year of graduate school, she worked 26 hours a week, a difficult feat as she began taking core courses, searching for internships and joining new extracurriculars.

“The biggest stressor, in my opinion, is the finances,” Park said. “Because if you can’t fund your education, you can’t get your education.”

This struggle is all too familiar to Velasco and other USP staff. In response, USP developed several fellowships and scholarships connecting students with textbooks, transportation funds and meal vouchers among other resources.

The USP also targets students who fall into the gaps of state and federal policies. Last summer, a US District Court in Texas found DACA to be unlawful, effectively preventing new applicants to the program in the country. Although President Joe Biden recently made an effort to codify DACA as a federal regulation, DACA still cannot accept new applicants.

USP recognizes that more undocumented students will be entering UCLA without work qualifications. To meet these students’ needs, USP developed the UndocuBruins Fellowship Program, which provides a $5,000 stipend to participating students and places them in workplaces across campus, Velasco said.

“We want to make sure that students who may not be able to benefit from DACA and students who may not have work authorization are still able to get important skills and experiences,” Velasco said.

Samantha Valdivia, an alumnus and former intern at USP, added there is a world of difference between undocumented and documented students when it comes to financing a college education.

“I think a game changer will always be financial help, especially because the way that financial aid works for undocumented students is very different versus someone who is documented,” Valdivia said.

Valdivia is no stranger to supporting the undocumented community. Prior to entering as a transfer student at UCLA, she worked at her former college’s dreamer center, which provided everything from financial aid support to legal services. Valdivia added that while she herself is not undocumented, coming from a mixed-status family has helped her recognize the importance of USP’s work.

Students such as Valdivia play a key role in USP’s leadership, Velasco said. Pulling from their personal insights and experiences, students help determine how funding from the UC Office of the President can be used to support undocumented individuals on UCLA’s campus, Velasco added.

For example, Valdivia said she offered students a safe space to express their fears following the 2020 presidential election. However, as she hosted wellness check-ins for undocumented Bruins, Valdivia couldn’t help but feel discouraged herself.

“That was the first time I voted. … I remember being very defeated,” Valdivia said.

Although there are resources available to the undocumented student community, students aren’t always comfortable seeking help. At the time of the 2020 election, Valdivia said the political climate only compounded their worries.

As a freshman, Park said she rarely interacted with USP because she felt uncomfortable disclosing her status. However, she added, her mentality has shifted since starting her graduate program. Seeing the confidence of her undocumented peers while also receiving robust support from faculty members has bolstered her sense of belonging at UCLA, she said.

“Having that community kind of did really help me feel less shy about my own identity,” Park said.

Entering into her final year at UCLA, Park has taken full advantage of the support USP can offer inside and outside of the classroom.

In 2021, Park spent her winter break visiting a national park – only to be stopped by border patrol agents in Texas for what she believes was a routine check. When questioned about her status, Park was unable to produce the employment authorization documents needed to prove her status as a DACA recipient.

“I don’t remember super clearly what exactly they (the officers) said, but I do remember driving out of that station feeling really worried and scared,” Park said.

The agents let Park go but warned her that her DACA status could be revoked the next time she failed to produce the necessary documents, Park recalled. Panicked by the agents’ threat that they would mark her records, Park turned to the UC Immigrant Legal Services Center, run in partnership with USP. With the center’s help, she filed a request to check the records maintained by U.S. Customs and Border Protection and was relieved to find them unmarked.

Park turned to the center once more for guidance as she filled out her DACA renewal form for 2022. The support she received from USP affirmed she is not alone on her journey as an undocumented student, she said.

“I usually file it on my own, and it’s kind of stressful, just feeling nervous about everything,” Park said. “It was really nice to have additional guidance and eyes to look at the documents before submitting.”

Moving forward, Velasco said he hopes to continually grow UCLA’s network of support for undocumented individuals. And that, of course, means turning to the school’s alumni.

Cuauhtemoc Salinas Martell is the first alumni coordinator for the UCLA Dream Resource Center, a project under the UCLA Labor Center. Founded in 2010, the DRC trains immigrant youth and allies to lead in social justice movements and research.

An undocumented student himself, Martell said he found solace in his education. After working as a summer fellow for UCLA’s DRC in 2012, he quickly recognized his passion for helping other undocumented students thrive in college and beyond.

The first alumni coordinator at the DRC, Martell is laying the foundation for the responsibilities of the role. His goals are to provide more gatherings and plan self-care events, including sending self-care packages to alumni. There are also plans to connect present and future alumni with job opportunities and scholarships via newsletters. Martell explained his vision for the alumni network is ultimately to build connections within the undocumented community.

“I really want them to feel like they’re a part of the family,” Martell said.

Valdivia agreed. She added that while she understands students’ hesitancy to reveal their undocumented status, she hopes they realize they are not alone.

“Having a community to back you up will make all the difference,” Valdivia said.

And for those entering the community as undocumented students or allies, Martell’s advice is simple.

“Lead with love, care for one another and make sure that you are impacting people everywhere you go,” Martell said. “That’s what I did with my advocacy. That’s what I did with my narrative. And that’s what I’m doing with my identities.”

Correction: The original version of this article incorrectly stated Jaymie Park thought she was a United States citizen before applying for college financial aid. In fact, she was unaware of her status before applying.