(Kyle Kotanchek/Daily Bruin)

By Kyle Kotanchek

May 1, 2022 at 2:42 p.m.

In 1929, UCLA’s campus officially opened, moving from its Vermont Avenue location to a then-barren desert. Since then, the campus has gone through multiple architectural movements.

Robert Gurval, a professor of classics, taught “UCLA Centennial Initiative: The Architecture of Westwood,” exploring buildings on campus and in Westwood.

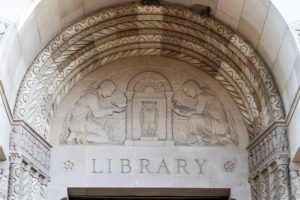

Royce Hall – along with Powell Library, Haines Hall and Renée and David Kaplan Hall – was designed in the Romanesque style of architecture, inspired by Lombard architecture from Northern Italy, Gurval said.

Students walk in front of Royce Hall.

The original four buildings of UCLA were Royce Hall, the College Library, the Chemistry Building and the Physics and Biology Building. The buildings are now called Royce Hall, Powell Library, Haines Hall and David and Renée Kaplan Hall, respectively.

UCLA’s first buildings feature small details and decorations that often have symbolic meaning.

Powell Library includes a sculptural relief above the main entrance. It features images of an owl, the sun, a lamp and a book – all of which were symbols of knowledge in ancient Greek and Islamic societies.

Gurval said the age of a building can be determined using its windows. The oldest buildings have stained, rounded windows. After the 1940s, there was a push toward larger, clear rectangular windows, Gurval added.

Kerckhoff Hall has pointed windows reminiscent of Gothic architecture. The Gothic design was meant to differentiate the student union building from the other Lombardic academic buildings.

The School of Law building was constructed in 1949 and features clear rectangular windows.

The push toward the minimalization of buildings is largely in relation to the post-World War II modernist movements, said Todd Lynch, an architecture professor at UCLA. Following the signing of the GI Bill, the United States government provided student loans to soldiers, increasing the demand for higher education. In this postwar era, people imagined the need for a new style of art and architecture to propel them into what they envisioned as the future, including larger and more flexible spaces, Lynch added.

The Court of Sciences features brutalist buildings with a large open space in the center.

In Schoenberg, white rectangular pillars support the building. During the modernist movement, columns were very straight and plain, contrasting with the ornamental columns and arches found in Romanesque architecture.

A feature of modernist architecture is the use of grids.

Bunche Hall, built in 1964, is illuminated in the sun. The building features a repeating grid of black windows.

In the 1960s and ‘70s, there came a new effort to unify the campus more. Architects took inspiration from the original four buildings, Lynch said.

Students walk in front of the Engineering VI building, which opened in 2018. Despite its modern look, it still has similarities to the oldest buildings on campus.

“The unity of the campus would be brick and then the blocks on concrete masonry blocks,” Gurval said. “Even the new buildings who use different materials often will try to echo this design.”

The lights of the Epicuria dining hall shine through Covel Commons’ windows. Epicuria opened in Fall 2021 as a renovation of the Covel Commons Residential Restaurant. The building blends the old style of Romanesque architecture with an updated design.

All bricks in UCLA are made of a particular UCLA blend of Pacific Clay that is fired locally, Lynch said.

Sidewalks on campus, along with many other buildings, incorporate the four-color blended bricks in some way or reflect their color scheme.

UCLA’s architecture designs had to adapt to the unique situation of limited land space and a rapidly growing population.

“We’re the smallest UC in terms of land size and the largest in population, so balancing that equation is really hard,” Lynch said.

As UCLA’s student population expanded in the 1960s, there was a necessity to accommodate the increasing need for parking while not using up limited land space. One solution was moving parking lots underground and on top of buildings to allow for heavy traffic. This also allowed for more open spaces and developed the greenery of campus.

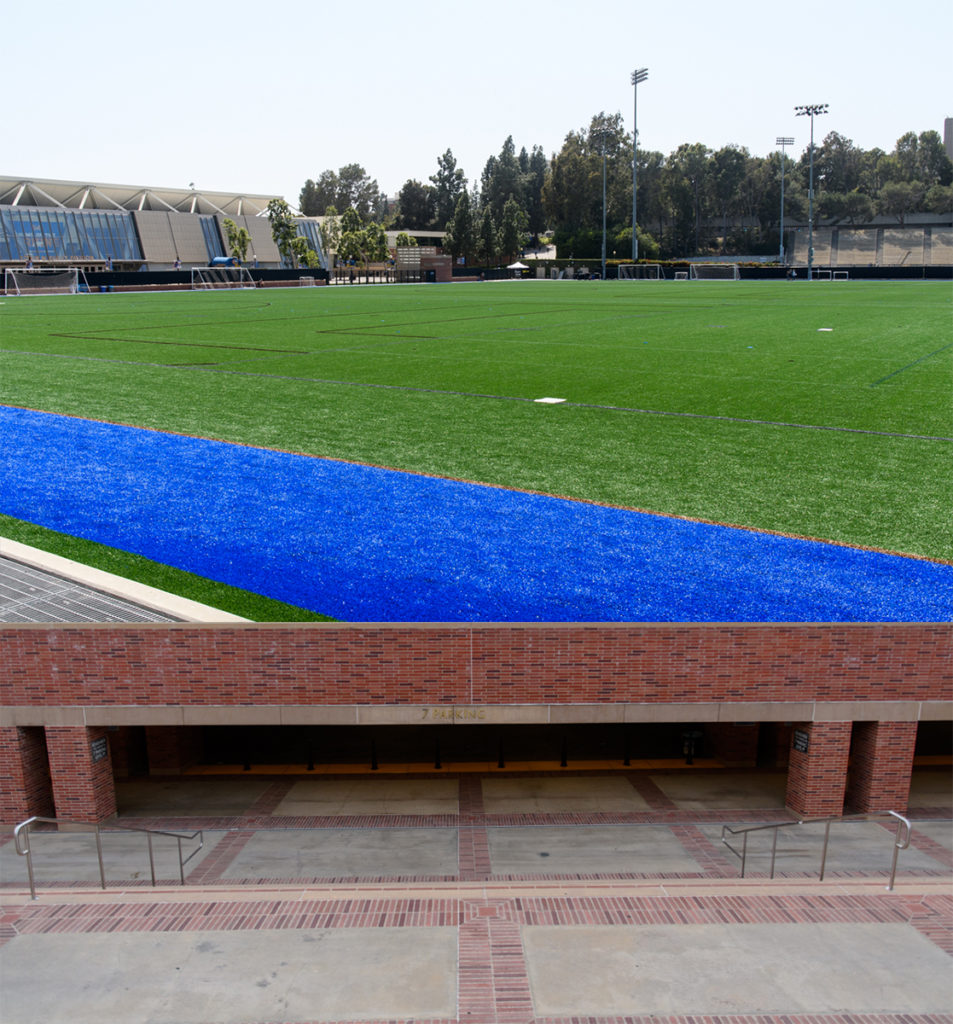

The Intramural Playing Field (pictured) is built on top of Parking Lot 7, enabling the parking structure to stay cool and for open, green spaces to be more prevalent on the UCLA campus.

In the early ‘70s, a postmodernist period began. Architects wanted to break away from the gridlike and blocky appearance of modernist architecture and return to ornamentation and attention to small details. Lynch said this resurgence was similar to UCLA’s original buildings built in the 1930s.

These postmodern buildings were designed to create natural airflow and be more inviting to outside observers, in contrast to uniform mid-century architecture built to keep air conditioning in, he added.

The Orthopedic Research Hospital Center (pictured) was built in 2007. The usage of brick and curved edges indicates that it was built after the 1980s.

Even the way buildings are named has changed over time. In general, buildings originally were named based on the subjects taught inside. Later, buildings became more commonly named after notable professors. Now, Lynch says, buildings are often named after donors and philanthropists.

Pritzker Hall (pictured) was finished in 1967. The building was formerly part of Franz Hall but was renamed following a donation made by the Pritzker family to restore the building.

Since 1929, UCLA’s campus has encountered multiple architectural movements while quickly expanding. In the future, UCLA will continue to grow while promoting sustainable initiatives through better usage of materials and less energy-intensive designs, Lynch said.

Still, the campus maintains a stylistic unity that binds together the past, present and future, Gurval said.