(Sakshi Joglekar/Daily Bruin staff)

By Sakshi Joglekar

December 23, 2020 at 3:15 p.m.

Daily Bruin staffer and third-year global studies student Sakshi Joglekar takes readers inside the depths of the U.S. Capitol building during the COVID-19 pandemic, recounting her internship experience in the nation’s capital city.

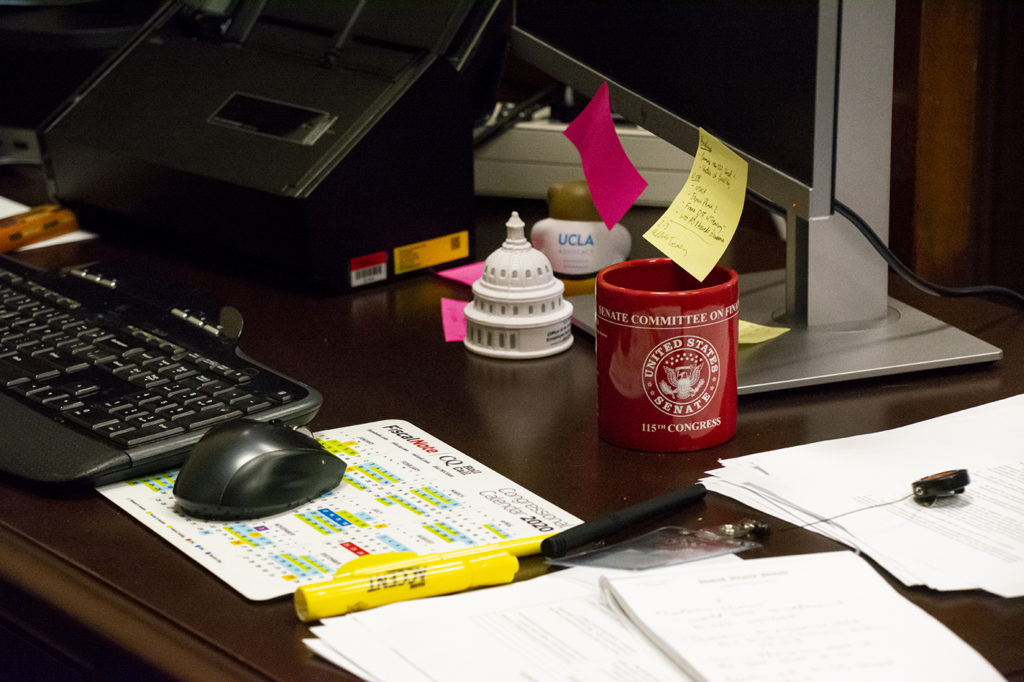

Working as a trade intern for the United States Senate Committee on Finance, I gained firsthand insight into how the nation’s capital functioned during the pandemic. Since most people worked from home, my internship was characterized by abandoned desks and empty offices but also bursts of optimism, acts of kindness by my coworkers and a lot of work done through phone calls and emails.

Despite my daily meetings, visits and walks in the Capitol, most of my day was spent in the Senate Finance Committee office in the Dirksen Senate Office Building.

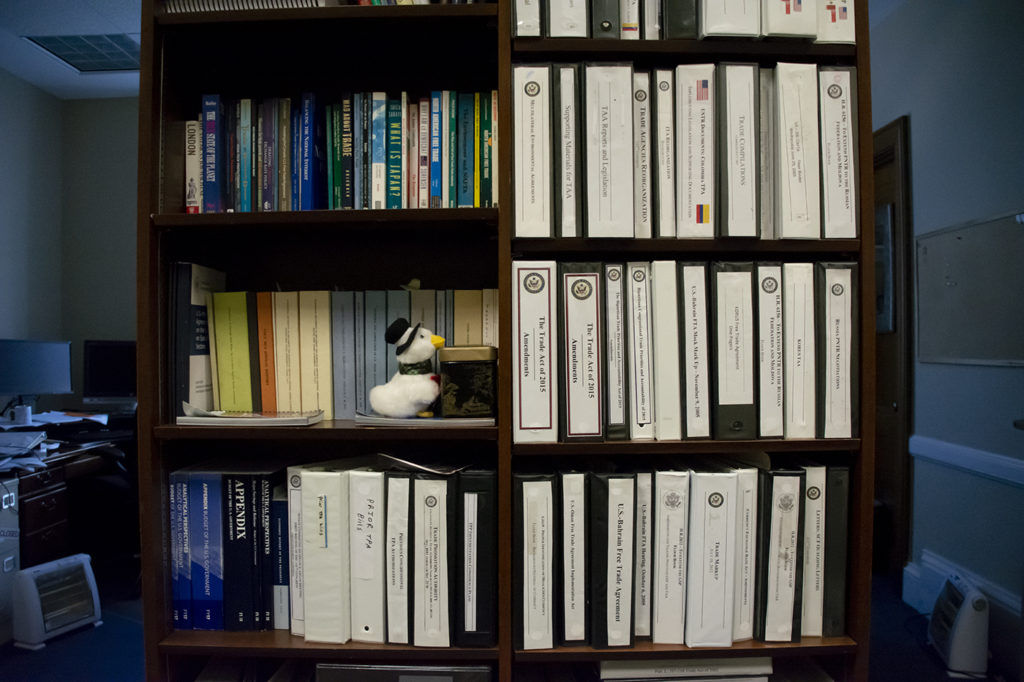

Every bill, amendment, trade agreement or project we worked on required research, phone calls and meetings. Most ultimately became a binder on one of the numerous bookshelves in the office and served as a physical reminder of the work we did, whether or not it was passed into law.

The staff also had several stuffed ducks given by Aflac over years of lobbying that they would hide around the office. There was no reward for finding them, but it gave staffers something fun to do in between meetings and phone calls. This one was not hidden very well.

One of my favorite things to do during break at work was visiting the Capitol. Because of the pandemic, no tourists or outside visitors were allowed, but staff members could enter through underground hallways, tunnels and trains.

Underground tunnels connect the Capitol to office buildings that host the offices belonging to members and committees of the Senate and House of Representatives, like the Senate Committee on Finance office I worked in.

There are three underground Capitol trains: two connecting Senate office buildings to the Capitol and one for House office buildings. I used the Dirksen monorail, an automatic train installed in 1993. The original subway line has been around since 1909. It took less than a minute for me to get to the Capitol building.

When I arrived at the basement of the Capitol, one of the six staff elevators was always ready to take me upstairs. An elevator operator was often present to direct traffic and make sure that no one had to wait a long time.

Usually, people come from around the world to visit the United States Capitol, starting off at the Capitol Visitor Center. The Visitor Center is about three-quarters the size of the Capitol itself and has direct access to the Senate and House floor. When I visited the Capitol with my South Carolinian high school, the room was packed. We waited in long lines and we even had lunch in the crowded cafeteria. Now, the halls are empty.

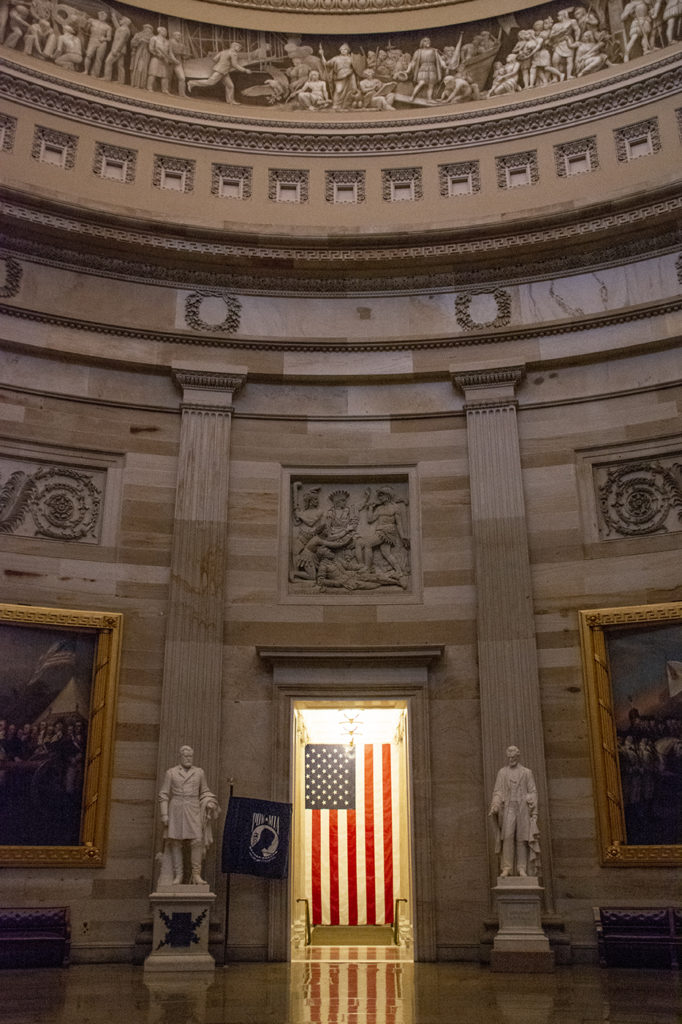

Every time I walked into the Capitol Rotunda, I couldn’t help but look up at the dome and the fresco inside of it. It never ceased to amaze me. The Rotunda, one of the most famous rooms of the Capitol, is normally used for ceremonial events like the dedication of works of art or the lying in state of esteemed Americans.

During my time in Washington, the Rotunda was often used to build furniture and refurbish statues. I loved sitting there and watching workers repair these historic pieces. Here, several projects are in progress in front of the painting “General George Washington Resigning His Commission” by John Trumbull, one of four revolutionary period scenes in the Rotunda.

My favorite part of the Rotunda is this image of George Washington surrounded by clouds, founding fathers, rainbows and an eagle. This “Apotheosis of Washington,” a fresco painted by Constantino Brumidi in 11 months following the Civil War, shows Washington flanked by 15 female figures representing liberty, victory and the 13 original colonies.

In the front, Armed Freedom and an eagle fight Tyranny and Kingly Power and to the left, the goddess Minerva teaches science to Benjamin Franklin, Robert Fulton and Samuel F.B. Morse. Apotheosis means glorifying a person to an ideal or elevating someone to the rank of a god.

I would often walk around the Capitol at the end of the day before heading home, and the rooms and hallways were largely empty and dark. Light shone from only a few rooms, like this hallway leading to the Speaker’s Balcony.

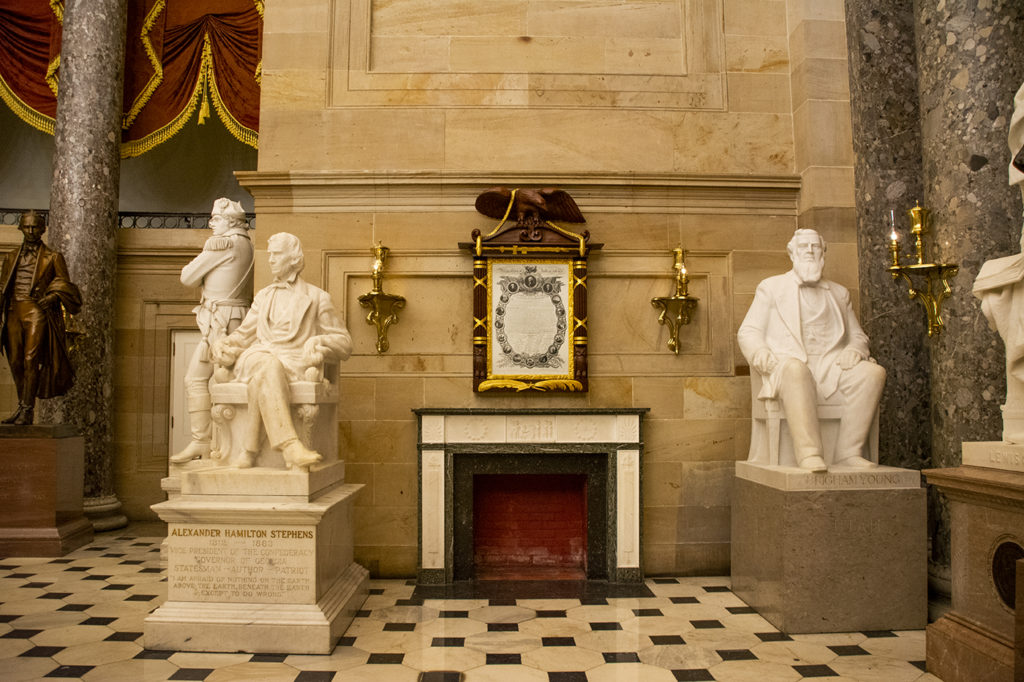

Just off the Rotunda is the National Statuary Hall. Every state has two statues, and this room held the collection until it became too extensive and it could no longer hold the weight of all the statues. In 1933, state statues were relocated all around the Capitol building and only 35 remain in the Hall today.

On a few days the Senate was not in session and work in the office was slow, I wandered the building to try to find the statues from my home state, South Carolina. Walking into the National Statuary Hall from the Rotunda, “Liberty and the Eagle” stared straight at me. “Liberty” has overlooked this room after the Capitol was rebuilt after the fire of 1814.

The National Statuary Hall used to be the House of Representatives before they moved into a larger chamber and the room was repurposed to hold statues in 1857. Statues guard the Lincoln Room, the office of the House Majority Whip, Rep. James Clyburn. His office sits next to the office of the Speaker of the House, Rep. Nancy Pelosi.

In a corner of the room, a framed copy of the Declaration of Independence hangs above one of the four fireplaces of the room. The first few times I went through the Hall, I didn’t even notice it sitting between two statues, alongside a heating system that allowed members to work during cold winter months.

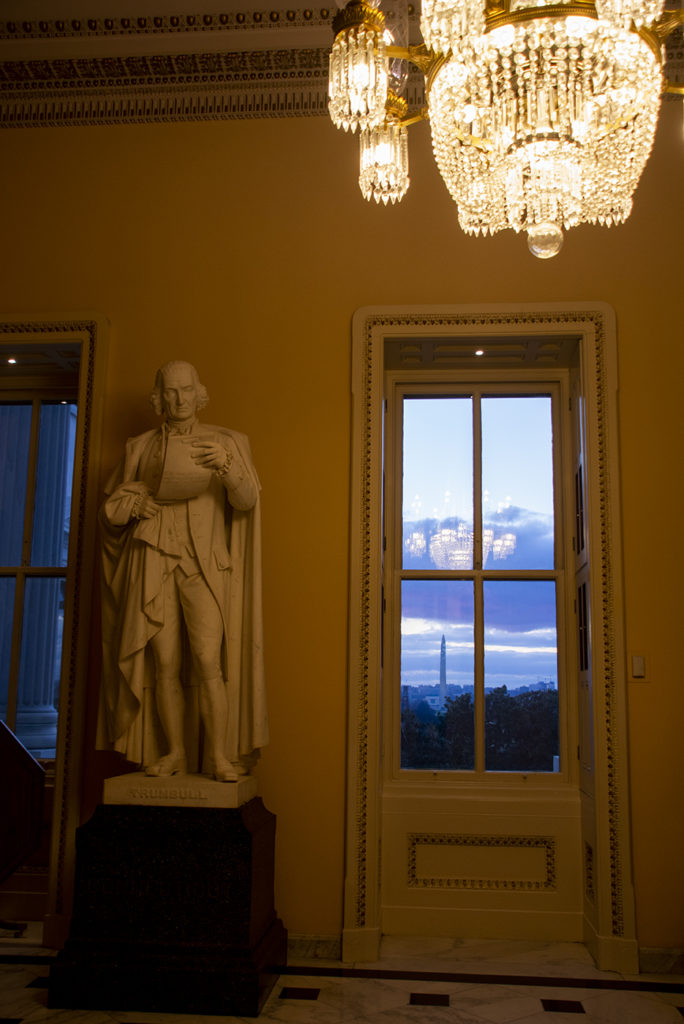

Even after months of interning on the Hill, I was always excited to get a peek at the Washington Monument. One of my favorite views from the Capitol was in this hallway, near the office of the House Majority Leader, Steny Hoyer. Seeing the monument over the balcony of the Capitol, in an area inaccessible to tourists, felt secluded and special to me.

A Connecticut state statue of Jonathan Trumbull guards the view of the Washington Monument. His son, John Trumbull, painted four of the eight paintings in the Capitol Rotunda.

The staff staircase that runs along the side of the Rotunda, through office hallways and down to the Crypt is different from the marble staircase used by tour groups. It was isolated and quiet with dim light and bare white walls.

This area directly below the Rotunda has long been referred to as the Crypt because of its similarity to the underground rooms or mausoleums in churches. Furthering this similarity, a tomb was built directly under the Capitol Crypt to house the remains of George Washington, but he requested to be buried at his home in Mount Vernon.

Ultimately, no one was buried, and the tomb was sealed in 1828. During my internship, I often had to cross through the Crypt to get to Senate offices in the basement of the Capitol. It was brightly lit and highly trafficked during the day, but I avoided the chamber at night.

I loved to stop and admire the different styles of ceilings in the Capitol building. It made sense for rooms like the National Statuary Hall and the Rotunda to have their wide, curved ceilings, gold icons and frescoed friezes. But this one, tucked away in the basement of the Capitol, inaccessible by tourists, surprised me with its detailed Americana imagery.

Off the tour path, one of the nine Senate dining halls, Senate Carry-Out, resides in the midst of the dim, crisscrossing hallways underneath the Capitol, making it difficult for an intern like myself to find it. It was one of the few dining halls that remained open for staff members during the pandemic.

Inside Scoop, another Senate dining hall, was also empty. I heard stories throughout my internship of Senate members and staffers alike socializing at these tables over ice cream. Now, it’s been converted to a grab-and-go self-serve snack bar. Three Senators can be seen buying items from a vending machine instead.

Walking to my car at the end of the day, I always stopped to look back at the Capitol. Its original sandstone was quarried by slaves, it burnt down and it was rebuilt and then expanded to fit a growing nation. Now, for the fifth time in a row, the current Congress is more diverse than ever, with more than one-fifth of voting members being racial or ethnic minorities.

Although I didn’t have the normal Hill internship experience, it was worthwhile and fulfilling to witness the hard work, reverence, frequent defeat and relentless optimism that the people I worked with had, even with a nearly empty Capitol building.