Getty Museum displays works by famed photographer Herb Ritts in new exhibit

Image Courtesy of The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles, Gift of Herb Ritts Foundation

By Lenika Cruz

April 9, 2012 11:36 p.m.

Image Courtesy of The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles, Gift of Herb Ritts Foundation

“Herb Ritts: L.A. Style”

Through Aug. 26

Getty Museum, FREE

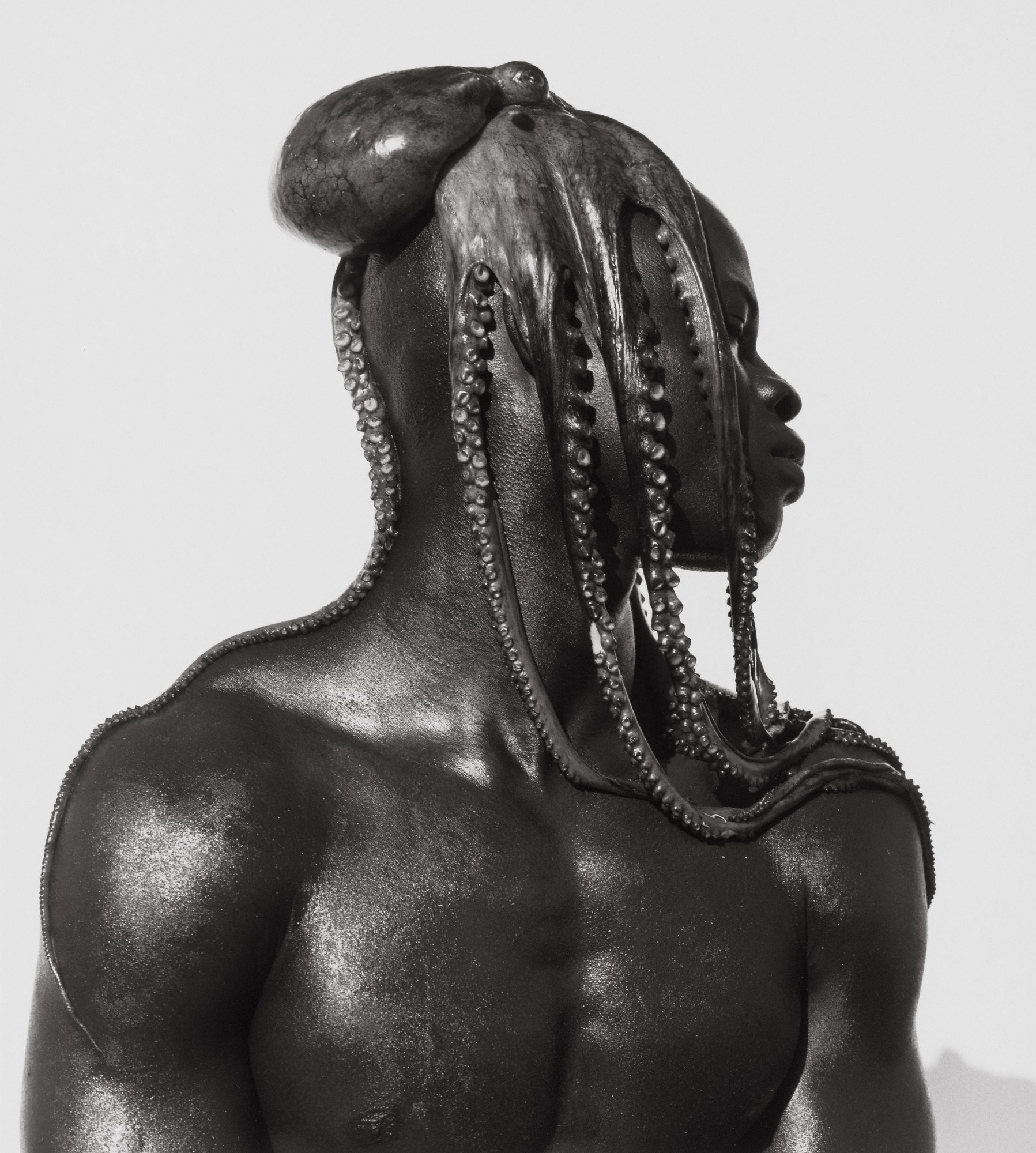

The model has a dead octopus on his head. In verbal terms, the image is crude and almost revolting, but in the hands of Herb Ritts, fashion photographer to the stars who himself attained a kind of celebrity status, it becomes a visual portrait of otherworldly, regal beauty.

From afar, the tentacles resemble an elegant headdress, which drapes across the model’s dark, muscular shoulders, transforming him into a kind of tribal chieftain. Only a closer look reveals the animal’s suction cups, bulbous head and bulging eyes, but Ritts delivers the image from cheap parody and elevates the strange to a pure iconicism.

The Getty Museum’s new exhibition, “Herb Ritts: L.A. Style,” offers a thoughtfully curated and extensive survey of Ritts’ work from 1984 to his death from HIV complications in 2002. During this time he shot more than 200 magazine covers for publications including Vogue, Rolling Stone and Vanity Fair, and photographed celebrities ranging from Naomi Campbell, John Paul Gaultier and Elizabeth Taylor to Johnny Depp, Britney Spears and Jackie Joyner-Kersee. He is also known for his nudes and photos that incorporate the symbolic and subtle beauties of the natural landscape.

The show is accompanied by a complementary exhibition, “Portraits of Renown: Photography and the Cult of Celebrity,” which offers a historical context for Ritts’ work.

According to the show’s curator Paul Martineau, Ritts actually denied having an “L.A. style” and did not want to be pegged as having one style or another. At the same time, much of Ritts’ work seems to adopt a distinctly Southern California aesthetic, from its fascination with Old Hollywood to body culture. In the ’80s, East Coast magazines and fashion houses dominated the field in terms of visual style, but with time, Ritts built a reputation that essentially enabled him to rewrite many of the rules of editorial and commercial photography.

Ritts used African and African American models at a time when many magazines shied away from depictions of racial diversity, particularly in fashion, and he paved the way for such publications to be more inclusive, Martineau said.

Ritts was both a perfectionist and a patient experimenter, the former when it came to the precision of lighting in a photo’s composition, the latter when dealing with models. According to Martineau, in “Djimon with Octopus, Hollywood 1989,” the model and future Academy Award-nominated actor Djimon Hounsou was utterly repulsed by Ritts’ suggestion that he place a dead octopus on his body, but Ritts managed to convinced him, and the serene photo that resulted smooths out Hounsou’s reluctance, betraying none of his anxiety.

“Sometimes celebrity photographers are criticized for relying too heavily on the star power of their sitters in order to make the pictures interesting,” Martineau said. “I looked for photos that were interesting on their own … where (Ritts) complicated the notion of celebrity portraiture.”

Sometimes Ritts shot celebrities from a side angle, or even of the backs of their heads. Occasionally, the limits of the frame dissected part of the sitter’s face, as with a photo of Christy Turlington from the jaw down.

Ritts’ portrait of Madonna taken for the album cover of “True Blue” recreates Olivia Newton-John’s pose for the cover of her LP “Physical” ““ the head tilted back, eyes closed as a kind of sign of sexual surrender and vulnerability. But Ritts balanced the softness of this pose with the hard angle of Madonna’s jaw, and the feminine sloping of her shoulders is accentuated by the hard, ruggedness of a black leather jacket. According to Martineau, Madonna is at once channeling soft glamour of Marilyn Monroe and the masculinity of James Dean, making her both iconic and accessible.

A hint of surrealist influence may also be traced through the show and back to Ritts’ admiration of Salvador Dali. In one photograph, a woman’s wet hair is pulled down tightly over her face like a mask, so that the depressions of her eye sockets create a ghoulish, skull-like vision. The slightly disturbing quality is subdued by the model’s naked torso and the way her hand gently sits on her cheek.

The advertising campaigns and music videos that Ritts later directed tread the line between artistic and commercial. After Madonna convinced a hesitant Ritts to direct her music video for “Cherish,” he became in-demand and shot videos for Janet Jackson, Michael Jackson and Chris Isaak. A separate, curtained viewing room in the gallery screens many of Ritts’ commercials and videos.

Martineau arranged pieces in a way that creates visual and historical relationships between different pieces in the show, enriching the multiple interpretive layers of Ritts’ photographs. Ritts’ primarily black-and-white photographs inject a deeply nuanced, sensitive and imaginative vitality into the way his viewers see.

As Martineau noted, “(Ritts) photographed you the way he wanted the world to see you.”