Critical studies necessary for long-term academic and social change

By Itak Moradi

Feb. 27, 2012 1:58 a.m.

The university is changing, and public sentiment seems to agree: It’s beginning to look a lot like a business. If revenue generation is replacing knowledge expansion as an end goal, it’s time students take it upon themselves to develop their critical thinking skills.

Chronic disinvestment in education and the resulting public dissatisfaction have called for a number of responses, from protests to proposals of alternative funding methods, to an unfortunately high dropout rate. Many have even questioned the value of a bachelor’s degree.

But I believe we need a longer-term commitment to making an impact. While defeating a tuition hike or improving UCLA’s budget allocations are important strides, they are also rooted in the present. But thinking about broader changes, even if they will only reap benefits for the future, is just as necessary as short-term action.

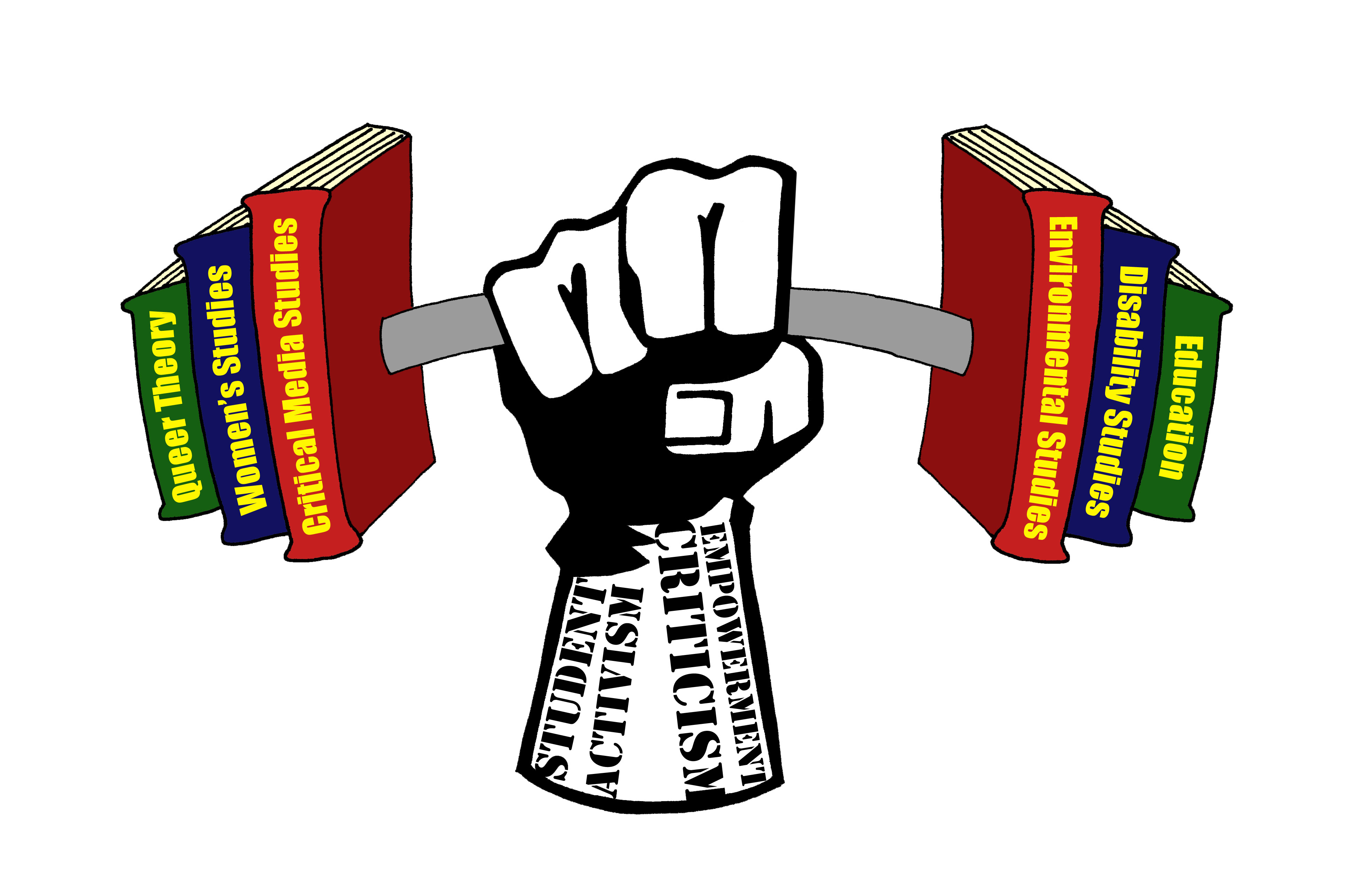

One important, easy and effective way students can make that commitment is by seeking classes in departments that depend on critical analysis.

In a recent piece in the Chronicle of Higher Education, Jeffrey J. Williams wrote of a developing field called “critical university studies” that takes opposition to changes in university practices by incorporating broader scholarly and activist perspectives.

As students, the role we occupy in society is unique. Theoretically, we are in the place that produces the very people socially legitimated to “make knowledge.” As such, the effort we place on challenging and diversifying our own bodies of knowledge has a direct impact on the future state of our society.

But what if the university intends to create producers for the capital world, instead of thinkers equipped with tools to make social change?

Critical studies are an integral means of understanding ideological underpinnings of social trends, one of which is how education has structurally changed for the worse. Academic disinvestment, inevitably tied to disinvestment in youth, is tied to much larger social ills.

Students rightfully feel frustration and despair about these economic and social issues, and the first step to thinking about a resolution is fully understanding why things are the way they are.

I mentioned that the university functions on a profit-based model, and this has to do with the commodification of education.

More and more, students are taught to adhere to a certain type of knowledge within one certain field and to take that knowledge as blind authority, said Kenneth Reinhard, director of the UCLA Program in Experimental Critical Theory and professor of comparative literature and English. But critiquing discourse is essential, he added.

Critical theory courses don’t necessarily depend on a pool of delineated knowledge, as other fields do, but instead expect students to pick apart their own knowledge. They are fields dedicated to uprooting the ideologies and assumptions of current political concerns, as well as historical ones.

Departments such as women’s studies, disability studies, global studies and labor and workplace studies equip students with so much more than an ability to understand and apply a field of information. They teach students how to create change, question structures, startle status quos and aspire for inclusive, anti-racist, anti-capitalist perspectives.

I don’t mean to downplay the importance of other fields. It was only three months ago that I wrote a column discussing the centrality of science, technology, engineering and mathematics (STEM) to social prosperity. But I can’t help question whether such fields tend to reinforce the idea of going to college simply to get a job.

In 2010, UCLA’s Higher Education Research Institute showed that student motivation to attend school for increasing their “earning power” is higher than ever before.

This trend signifies an opportunity for hegemonic ideas to continue unquestioned in our flawed educational structure.

While researching this topic, I came across a scholarly piece, “The Impact of Neoliberalism on College Students,” with similar sentiments as mine, but by the end, the author, Daniel Saunders, only made a call for more research that would connect changes in the university with its broader impact. He believed such work is the only way to begin rebuilding our institutions, and shaping our educational future.

This argument displaces student agency. We certainly have the ability to enact change in the systems we navigate. But first, let’s commit ourselves to questioning them.

Do you think critical thinking skills are undervalued? Email Moradi at [email protected]. Send general comments to

[email protected] or tweet us @DBOpinion.