Former UCLA cheerleaders speak to unhealthy standards expected of them

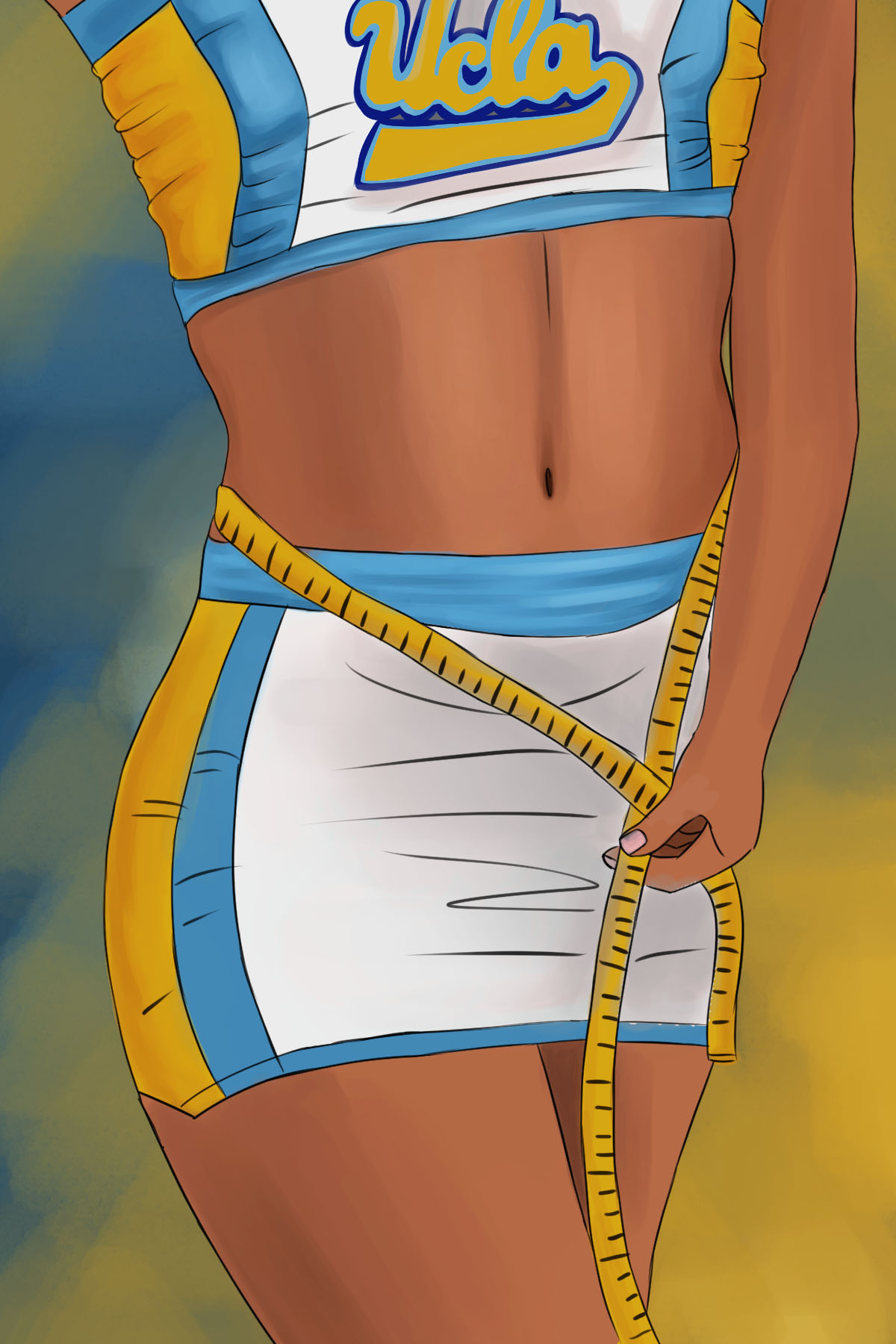

(Nicole Anisgard Parra/Daily Bruin)

By David Gottlieb

May 30, 2018 1:13 a.m.

The UCLA cheerleading team met for its first practice of 2015 shortly after the new year.

“It was the practice after Christmas break, so we had all been drinking and eating cookies and doing Christmas things,” said a 2014-16 UCLA cheerleader who spoke on the condition of anonymity. “We were just practicing – whatever – and he goes, ‘OK girls, go take your shirts off.'”

Kyle Bruich, then the team’s head coach, told the cheerleaders to stand in a line with their hands behind their backs. He walked up and down the line and stared at the cheerleaders. Eventually, he singled out two women.

“He said, ‘You and you, come talk to me. The rest of you can go put your shirts back on and get water,'” the 2014-16 cheerleader said.

He told them he wasn’t sure if they would be able to continue cheering with their current physiques and showed them how to apply bronzer to their stomachs.

Bruich was not immediately available for comment.

Another former cheerleader, a member of the 2015-16 team, had a similar run-in with Bruich and spirit squad director Mollie Vehling at an open gym session before she auditioned for the team.

Vehling oversees UCLA’s cheer team, dance team and yell crew. She was on the dance team as a student at UCLA, and has been spirit squad director ever since she graduated in 1999. Last season was Bruich’s final year as head coach of UCLA cheerleading.

The two shared some advice with the cheerleader in the weeks leading up to tryouts in 2015.

“They told me I needed to get more fit,” the 2015-16 cheerleader said. “I believe their words were, ‘tone up’ before tryouts. So I did.”

She restricted her diet to yogurt in the morning, an apple for lunch and a salad for dinner, and went to the gym every day before the tryout.

“When I finally was ‘fit’ enough, I tried out,” she said. “I was probably the lowest I had ever been weight-wise, and they said I looked good.”

Female cheerleading candidates wear a sports bra and shorts for the entirety of cheer auditions. The judging panel is made up of more than a dozen people, including former UCLA cheerleaders, dance professionals and donors, who assign the candidates numerical scores based on their performance.

Judges turn in their score sheets to the end of the table, where they’re added up on a computer. Vehling said the candidate’s final score is the only factor that determines who makes the team. Coaches do not sit on the judging panel, but they help facilitate the audition process.

Cheerleaders are allowed to go into Vehling’s office to see their score sheets, and the 2014-16 cheerleader said she remembers seeing comments on her sheet about her appearance that made her feel uncomfortable. She tried out when she was still a high school senior, and saw a note that said “nice athletic physique” on that year’s sheet.

“I was like, ‘Someone’s looking at me like that while I’m trying to just do a dance to make a cheerleading team?’,” she said. “I thought that was kind of weird.”

She tried out again two years later and didn’t make the team – something Vehling said was very rare – so she went to take another look at that score sheet. She saw the words “push fitness of lower body” in what appeared to her to be a man’s handwriting, she said.

“That was the one that got me the most,” she said. “I even showed (Vehling) and I was like, ‘Are you serious?’ I felt really confident and that pushes a button with me … It was just a bummer because I felt really, really good that day.”

Both the 2014-16 cheerleader and the 2015-16 cheerleader did not make the team following that year’s audition, and both said they had gained a small amount of weight – under 10 pounds – since the prior auditions that got them on the team.

Vehling said there is a safety component to the fitness and athleticism demanded of the cheerleaders’ performance with the team.

“They need to stay fit for their own safety and, in cheer, specifically for the safety of their teammates,” Vehling said. “If they are not fit and able to execute the skills, they’re jeopardizing other people’s skills as well.”

Jedrix Aquino is a former UCLA cheerleader who has served on the judging panel consistently for the last half decade. A former teammate of Bruich’s when they were both cheering at UCLA, he has judged cheer competitions internationally.

“Let’s say one of the candidates was a bit overweight,” Aquino said. “We don’t have to call out the fact that she’s overweight, because the stunt, the sport itself, it kind of demands that there’s a certain level of fitness that you need to have.”

Aquino said at no point are the judges ever told to evaluate how the performers look, but he has noticed a pattern.

“You will find a very high correlation between the candidates that are able to perform all of those skills, and perform them well, and those who just have a little bit more of an athletic look,” Aquino said.

Although the selection process was designed to be objective, Vehling said there are elements that are more subjective. The 100-point scoring system has a 10-point “posture” section that includes “audience appeal” and a 20-point interview portion with aspects like “sincerity” and “personality.”

“That’s why we have a deep pool of judges,” Vehling said. “What may appeal to one doesn’t appeal to someone else.”

Christian Youngers served on the judging panel for one year because he was the drum major of the marching band while he was a student at UCLA. Youngers said he found it difficult to assign numbers to the more subjective categories, so he decided to keep his variance in scores small in those categories.

“It was kind of hard to evaluate most of those,” Youngers said. “I would give between 1-2 points’ difference. I wouldn’t give one person a zero over a 10. It just didn’t make sense to do that to me.”

Aquino said weighting the interview and appearance sections is important to ensure the cheerleaders are ideal representatives of UCLA.

“When it comes to their appearance and how they present themselves, that is not just a measure of how they look,” Aquino said. “We’re in the entertainment capital of the world, in the media hotbed; there’s going to be a lot of opportunities where they may be stopped by a reporter, they may show up on TV … we’re an elite institution in terms of academic excellence, athletic prowess; you want those things to come through.”

Cheerleaders participate in a photo shoot just after being selected for the team, in which they take a myriad of group and individual photos. The 2014-16 cheerleader recalled coaches like Vehling and Bruich giving directions such as telling the women to flex harder, hold basketballs to conceal their stomachs or change uniforms.

“I mean, yeah, it sucks to be told, ‘I think you should try the other uniform – the one that covers your stomach,'” she said.

Vehling meets with cheerleaders throughout the year, and some of those meetings earned a two-word nickname with a group of women on the team.

“Oh yeah, we refer to the ‘fat talk’ all the time,” the 2014-16 cheerleader said. “Oh, so-and-so had the fat talk yesterday or after practice.”

The 2014-16 cheerleader recalled a midyear meeting with Vehling in which the spirit squad director encouraged her to lose weight.

“She basically said, ‘You look great, but I think you’d be so happy if you lost five pounds. You would just be so happy. You would feel so confident’,” the 2014-16 cheerleader said.

She stopped eating bread for a couple weeks, but started again after she developed headaches. The conversation haunted her for the next year or two, she said.

Vehling said her meetings with students focus on their development and that when wellness issues arise, she does her best to point students to health resources at UCLA.

“The expectations are really making sure that they are taking care of their bodies so that they’re at the level to perform and they’re not setting themselves up for injury or the body issues,” Vehling said. “That comes with the package. They’re in a very small uniform in front of hundreds of thousands of people; that’s inevitably part of the pressure.”

The spirit squad does not fall under UCLA athletics, so Vehling doesn’t have the same access to nutritionists and trainers as do UCLA’s Division I coaching staff.

She does put together a spirit squad “boot camp” designed to prepare the cheerleaders for everything that comes with being on the team, including safety precautions, how to deal with stalkers and wellness strategies.

Last summer, Vehling contracted out UCLA athletics’ Athletic Performance Dietician – Lauren Papanos – to speak with the team. Papanos was a cheerleader in college and works with the UCLA athletics programs that her team designates as high risk for developing food-related mental health issues.

Papanos said she is able to screen athletes and educate them on strategies for dealing with the mental health component of food, especially in a one-on-one context. However, her individualized work with the spirit squad has been limited, she added.

Vehling was able to pay Papanos for the team event over the summer, but when fall came, some UCLA cheerleaders paid out of pocket for Papanos’ individualized nutrition consulting – where she aims to instill confidence in her clients in how much they should be eating, when they should be eating, what kinds of foods they should be eating – and she hasn’t worked with the team since.

“I think some of them need a little bit more hands-on and one-on-one time than do the rest of them,” Papanos said. “That’s really where you just have to know how to individualize it.”

Vehling said she points cheerleaders who might have eating disorders or other body image issues to professionals like Papanos.

“I’m not trained to properly diagnose or treat (eating disorders), so we make sure to connect them with every resource that we have on campus,” Vehling said.

Danyale McCurdy-McKinnon, a UCLA researcher who studies eating disorders, said studies have shown that certain aspects of the sport put cheerleaders at increased risk for eating disorders, including midriff-baring uniforms, and focus on the stomach and weight.

She added the spirit squad evaluating cheerleaders in sports bras and shorts and asking them to apply bronzer to their stomachs or hold basketballs to cover them could cause feelings of body dysmorphia. College cheerleaders are already at an increased risk of developing eating disorders because they are typically young women and are going through the major life change of transitioning to college, which can cause adjustment issues, she said.

“Focus on the stomach tends to exacerbate dysmorphic feelings and sometimes eating pathology,” McCurdy-McKinnon said. “A vast majority of people with eating disorders do have a focus on their stomach and that’s partially related to … the ideal body type for women in the (United States), which is a small waist and bigger hips and breasts.”

However, she cautioned that risk factors do not always contribute to a lifelong battle with an eating disorder.

“Even the most healthiest and confident of people, when they have pressure to perform, will try to lose weight,” she said. “I’m sure every (cheerleader) experiences eating pathology or disordered eating, but being diagnosed with an eating disorder is a different thing.”

Bruich has been replaced by Travis Neese, who spent last season as an assistant coach for UCLA. Both Neese and Vehling said they had never heard complaints about Bruich being negative or insensitive about the cheerleaders’ bodies.

Neese offered his own take on the issue at one of the newly-announced 2018-19 team’s practices.

“I think in my time at UCLA, I haven’t seen that,” Neese said. “It’s not my philosophy. It’s not the philosophy of where this program is. Whether it’s yell, dance, or cheer, we really try and instill in them each person is built differently, we work with them to make sure that for their body type, whether it’s the guys or the girls, we’re helping them be the best they can be.”

Nonetheless, the 2014-16 cheerleader was shaking as she recalled that first practice of 2015.

“I remember walking away just so, so, so mad that I was in a program like that,” she said. “And that UCLA was putting me in that type of situation. And putting those girls in that situation.”

Contributing reports by Kelsey Angus and Madeleine Pauker, Daily Bruin senior staff.

The National Eating Disorders Association operates a (800) 931-2237 hotline Monday through Thursday from 9 a.m. to 9 p.m. and Friday from 9 a.m. to 5 p.m. Eastern Standard Time. UCLA Counseling and Psychological Services provides short-term individual therapy, psychiatry, group therapy, planning to help students connect with off-campus services and wellness groups for students seeking eating disorder treatment.