Playing the Villain: Fights for survival in sci-fi create relatable villains, inspire sympathy

(Photo courtesy of Bago Games)

By Tiger Zhong

Feb. 28, 2018 11:43 p.m.

A movie is only as good as its villain, and a good villain is much more than a monster with maniacal laughter or a sinister-looking entity surrounded by henchmen. From the anarchist Joker to the cunning and brutal Annie Wilkes, countless successful films have earned their iconic status thanks to their antagonists. Each week, columnist Tiger Zhong will discuss the strengths and the weaknesses of the villains from new releases as well as classics, exemplifying the narrative effects of their villainous acts. And yes, there will be spoilers.

Betrayal is one of the worst crimes a villain can commit – but coming from a humanoid robot and a lonely scientist, it becomes more forgivable.

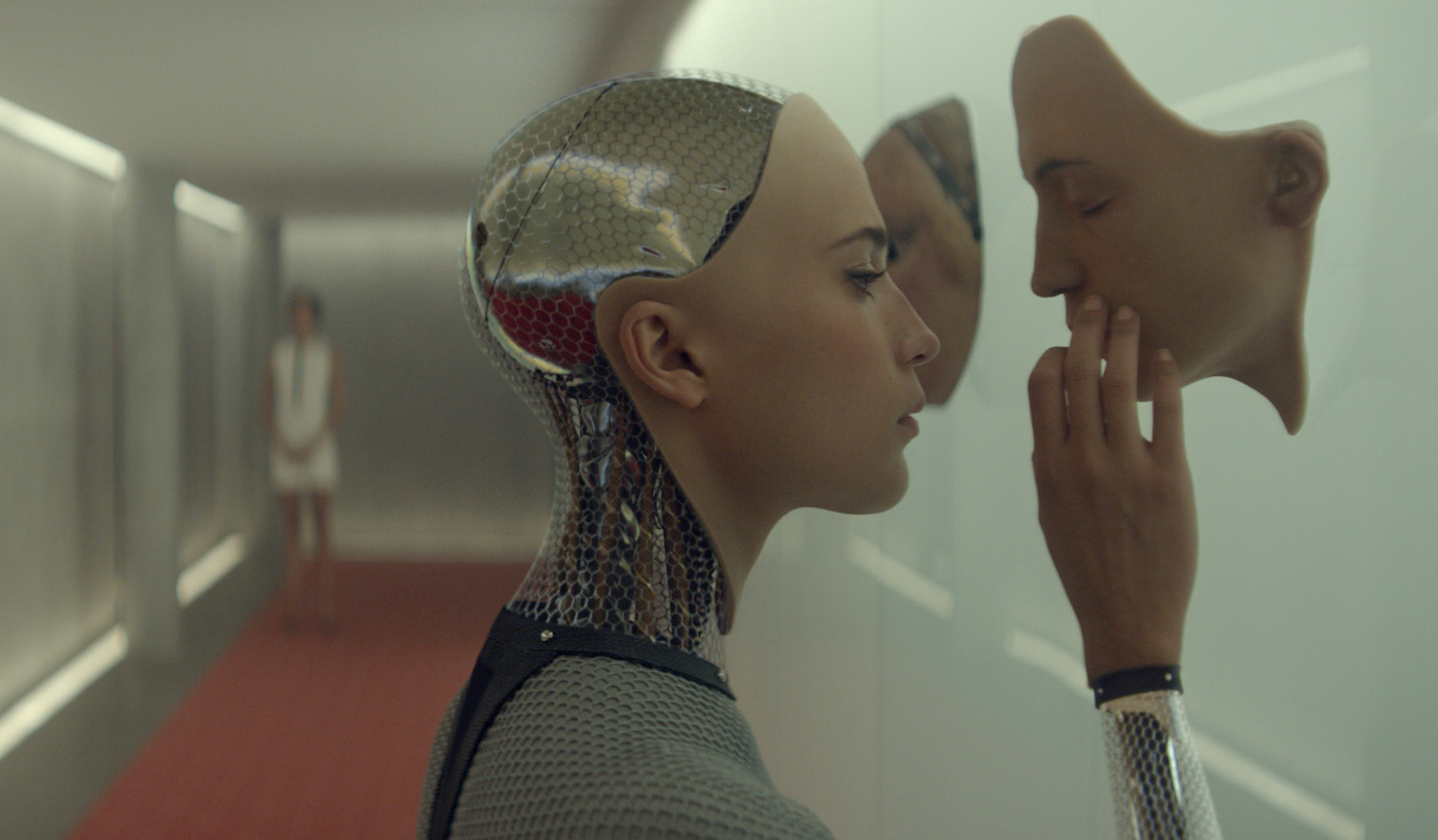

As sci-fi flick “Annihilation” garners praise, director Alex Garland’s past work has also re-entered the public eye. Among these past works is the 2015 film “Ex Machina,” which stole the hearts of hardcore sci-fi fans with its intricate plot and standout performances by Domhnall Gleeson, Alicia Vikander and Oscar Isaac. The betrayer in the film is the character Ava, a synthetic, intelligent robot who murders her own creator.

The betrayal presented in “Ex Machina” evokes themes from another great sci-fi movie, “Interstellar,” in which Dr. Mann, played by Matt Damon, betrays NASA. Instead of completing his mission to find a new habitat for humanity, Dr. Mann sends falsified data to scientists on Earth in an effort to escape the planet he has been stranded on.

In both “Ex Machina” and “Interstellar,” the villains desert their initial purpose in search of personal freedom. Their actions reflect basic human tendencies to seek autonomy and survival, which audience members can relate to.

“Ex Machina” tells the story of a young programmer, Caleb Smith, who participates in a test to determine the human qualities of Ava, a highly advanced and humanoid artificial intelligence. However, Ava’s ability to demonstrate humanistic characteristics such as consciousness and sentimentality causes her to realize she is imprisoned by her creator in the lab, and that she will only ever be a scientific experiment if she does not escape.

Ava’s seemingly villainous actions stem not from an inherently evil design, but rather from her realization that betrayal is her only escape. Her desire for freedom and independence makes her relatable, justifying her seemingly villainous actions.

Similarly, “Interstellar” features one of the most memorable betrayals in recent sci-fi movies. When protagonist Cooper and his team find the stranded Dr. Mann, he unsuccessfully attempts to murder them and use their spacecraft to go home.

But when Mann killed himself in an on-screen spacecraft accident, I couldn’t help but feel mixed emotions. On the one hand, I enjoyed watching the death of a scientist who chose to backstab his crew. But on the other, there was a certain sadness in seeing the failure of a man who died trying to get back home.

Mann’s betrayal of NASA is rooted not in his inherent evilness but in his justifiable fear of dying alone. Sci-fi films are often about extraordinary events that audiences will never experience, but their themes, such as isolation and selfishness, are what allow viewers to connect with characters – including villains – on a personal level. We relate to Dr. Mann not because we approve of his betrayal, but because we understand his fight for survival.

By giving their villains complex character arcs, “Ex Machina” and “Interstellar” highlight how sci-fi movies, regardless of their grandiose setting and outlandish spectacle, succeed in relating to their audiences – by displaying aspects of humanity, both beautiful and ugly, that audiences can identify with. The wrongdoings of Ava and Dr. Mann reflect not just their own human desires for freedom and companionship, but also their audience members’ desires.

In the floating remains of Dr. Mann and the artificial eyes of Ava, we can all see our own reflections, whether we want to admit it or not.